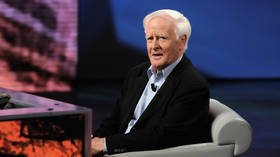

Thinker Writer Radical Spy: Just how close to the security services was John le Carré during his writing career?

The recently departed writer occupied a strange space in the spectrum of spy authors. He was simultaneously one of British intelligence’s most respected and beloved representatives while also seen as one of its foremost critics.

The demise of one of the world’s most famous spy authors leaves us with many unresolved questions. Who was le Carré? Where did his loyalties lie? Should we read his books as thinly fictionalised revelations about the crimes and corruption of MI5 and MI6, or as adverts for these agencies and their role in the world?

Unlike many real-life spies turned-spy authors, le Carré, born David Cornwell, did not present the world of espionage and covert operations as glamorous or exciting. His novels are replete with endless details and ambiguities, often frustratingly so, making it impossible to draw clear distinctions between heroes and villains.

This view of the world is in sharp contrast with the morally black and white worlds created by other British intelligence officers who have written spy novels, such as Ian Fleming and former head of MI5 Stella Rimington. In their tales, the heroes might do a few wrongs, but it is always for the ‘right’ reason, namely, the advancement of the ambitions of the British establishment and its allies.

Also on rt.com British spy-turned-novelist John le Carré, author of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, dies aged 89The Politicisation of intelligence

It is precisely this corporate-backed, empire-driven worldview that is so prominent in the novels of Fleming and his cohorts that le Carré began to oppose in his later life. The Iraq War of 2003 was a critical turning point, as it saw le Carré add his voice to the chorus of those opposing the invasion. In January 2003, he published an essay titled ‘The United States of America Has Gone Mad’ in which he declared, “America has entered one of its periods of historical madness, but this is the worst I can remember: worse than McCarthyism, worse than the Bay of Pigs and in the long term potentially more disastrous than the Vietnam War.”

The essay went on to note the corporate motives behind the Iraq War, and how many members of the Bush administration had deep ties to major oil corporations, asking, “Care for a few pointers? George W. Bush, 1978-84: senior executive, Arbusto Energy/Bush Exploration, an oil company; 1986-90: senior executive of the Harken oil company. Dick Cheney, 1995-2000: chief executive of the Halliburton oil company. Condoleezza Rice, 1991-2000: senior executive with the Chevron oil company, which named an oil tanker after her. And so on.”

Just weeks after publishing these words, le Carré joined the millions of Britons in marching against the war.

As the truth became clear about the intelligence used to justify the Iraq invasion, le Carré became even more outspoken. In a 2010 interview with Democracy Now to promote his book ‘Our Kind of Traitor’, he took aim at the role intelligence agencies play in advancing the Western corporate empire.

Le Carré said, “What I fear I have seen in the run-up to the Iraq war in this country is the politicization of intelligence to fit the political intentions of our masters. And to my mind, that was a terrible moment in the history, the visible history, of intelligence work in this country, where the intelligence service itself became effectively co-author and signatory to the so-called dodgy dossier, on the strength of which Colin Powell was able to present a dire picture of the threat from Iraq, which turned out to be untrue.”

He went on to excoriate former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, saying, “I can’t understand that Blair has an afterlife at all. It seems to me that any politician who takes his country to war under false pretences has committed the ultimate sin. I think that a war in which we refuse to accept the body count of those that we kill is also a war of which we should be ashamed.”

Also on rt.com ‘75,000 Russian informants’: UK think tank report mocked after they conduct only 16 interviewsBlowback from MI6

The former spy also offered a perspective on the never-ending tensions between the Western powers and Iran, commenting, “If people knew basically, for example, what we had done in Iran when we ousted Mosaddeq through the CIA and the Secret Service here across the way, and installed the Shah and trained his ghastly secret police force in all the black arts, the SAVAK, if people understood the extent to which we had humiliated Iran, then they would understand the later developments in Iran and Iran’s posture now. If people would look at the map and see the extent to which Iran is encircled by nuclear powers, they wouldn’t take it perhaps quite so seriously that Iran is seeking to arm itself with – if it is – with nuclear weapons.”

He added, “I remain terrified of the capacity of the media, the capacity of spin doctors, here and abroad, particularly the United States media, to perpetuate lies.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, MI6 were not happy with le Carré’s increasingly radical statements and he faced blowback for becoming such a public critic of British intelligence, and the wider empire of the Atlantic alliance. In 2019, the former head of MI6, Richard Dearlove, told attendees at the Cliveden Literary Festival, “We’ve all enjoyed enormously reading the Smiley books… and he does capture some of the essence of what it was like in the Cold War. However, he is so corrosive in his view of MI6 that most professional SIS [Secret Intelligence Service] officers are pretty angry with him… I rather resent the fact that he is trading on his knowledge and his reputation, and yet the feeling I get is that he intensely dislikes the service and what it represents.”

Dearlove waited until le Carré’s death before sticking in the boot in again, telling the Telegraph this week, “Because he was a great story teller, inevitably his pen both enhanced the mystique of MI6, but also stained its reputation – and there was a large dollop of vitriol in his ink for MI6. The impression that he leaves – and it lingers to this day – of the workings of MI6 is corrosive.”

Of course, Dearlove has both personal and professional reasons to speak ill of the dead and try to get the last word – he was head of MI6 during the run-up to the Iraq War, and is therefore heavily implicated in le Carré’s criticisms. Indeed, the infamous Downing Street memo refers to Dearlove, saying, “C (Chief of the SIS) reported on his recent talks in Washington. There was a perceptible shift in attitude. Military action was now seen as inevitable. Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy.”

Also on rt.com Russian embassy ‘spy-nest’: British media brings its anti-Russia hysteria to Ireland‘No James Bond work’

So, do spy novels like le Carré’s “enhance the mystique of MI6” or “stain its reputation”?

A large proportion of Britain’s most prominent spy authors worked for British intelligence, either before or during their writing careers. John Buchan, whose 1915 novel ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’ practically created the British spy story genre, worked for a military intelligence propaganda unit during World War I. Likewise, the first authorised history of MI6 confirmed that most of the early writers in the genre, including Somerset Maugham, Compton Mackenzie, and Arthur Ransome also worked for British intelligence during the war. World War II birthed a new generation of spies turned-authors, including Fleming, Graham Greene, Len Deighton, and Malcolm Muggeridge. Even John Bingham – the basis for le Carré’s character George Smiley – wrote spy novels while working as a spy.

Of this second generation, only Greene presented a critical depiction of geopolitics and covert operations, and for his troubles he was spied on by the FBI as a suspected communist.

The dominance of the spy fiction genre by real spies continued into the Cold War and includes Frederick Forsyth, who revealed in his 2015 autobiography that he was recruited by MI6 in 1968 – three years before he published his first novel, ‘The Day of the Jackal’. In an interview, he downplayed the 20 years that he spent working for MI6, describing it as “just running a couple of errands – no James Bond work, that’s just ridiculous.” Reflecting the same morally clear world of his novels, he explained that, “The zeitgeist was different. The Cold War was very much on. If someone asked, ‘Can you see your way clear to do us a favour?’ it was very hard to say No.”

However, he also revealed that he sent sections of his novels to MI6 for their approval, saying they gave him a number to ring when he had passages for them to review, and was told, “Send us the pages and we will vet them, and if they are too sensitive, we will ask you not to continue,” adding, “But usually the response was: OK, Freddie!”

Also on rt.com Desperately seeking spies: British intelligence is advertising for Russian-speaking spooksMI6 vetting of spy novels

Forsyth’s admission raises an interesting question – how many of these spy-authors submitted their works to the very intelligence agencies that they depicted in their books? And does this turn those novels and memoirs into de facto state-sanctioned propaganda?

Certainly, Ian Fleming submitted all of his James Bond novels to the Foreign Office prior to publishing them, to ensure that nothing in them met with their disapproval. He also maintained a good relationship with Allen Dulles of the CIA, which led to the later Bond novels becoming adverts not just for MI6, but for its American counterpart as well.

This review process has not been without its complications. In 2012, Dame Stella Rimington called for an overhaul of the entire process after problems with the reviewing and vetting of her memoir, ‘Open Secret: From Bored Housewife to Head of the Secret Service’. Around the time of Rimington’s public objections, MI6 consulted with the CIA on the issue of pre-publication vetting. For decades, the CIA’s Publications Review Board has vetted everything written and published by former CIA officers, from autobiographies to screenplays, but it is unclear if MI6 have set up their own in-house equivalent.

What about le Carré’s novels? According to an NSA document, he submitted all of his novels for review by British intelligence up until ‘A Perfect Spy’ in 1986. It is noticeable that his works after this point became broader in scope, always incorporating tradecraft and skullduggery but weaving in real life trends.

While his earlier novels focus on counterintelligence and covert operations, his later books incorporate government and corporate malfeasance, such as in ‘Our Kind of Traitor’, which homes in on how money laundering for billionaires and drug cartels is crucial to the banking system. Similarly, ‘The Tailor of Panama’ centres around an MI6 agent sent to look after British trade interests in the Panama Canal, while ‘The Constant Gardner’ reveals a plot by big pharma to conduct human experimentation in Africa.

Nonetheless, le Carré maintained a fairly romantic view of intelligence work until his later years. In his final interview for British TV, he spoke of his ‘informal’ recruitment by British intelligence when he was a student in Switzerland, saying, “It was in those days definitely a calling, and for all that I’ve written about it, it was a pretty decent calling, in the sense that we were very patriotic people, which I don’t think we are any more.” When prompted by Jon Snow to talk about the ‘dirty side’ of secret agents, le Carré commented, “That was the other part of the calling, so to speak. The message was that someone has to clean the drains, so we’ll do it.”

Perhaps this message sums up le Carré’s view of intelligence agencies, despite his increasingly critical outlook, that someone has to police a complex and dangerous world, so it might as well be MI5 and MI6. Just like with his novels, we are left with more questions than answers, and le Carré will remain an enigma that researchers may struggle to ever crack.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.