Rambouillet ruse? Why Trump could be setting up his North Korea talks to fail

President Trump has set the bar of success so high for his forthcoming meeting with Kim Jong-un, it is difficult to see how it could possibly be met.

As the New York Times noted last month, “To meet his own definition of success, Mr. Trump will have to persuade Mr. Kim to accept ‘complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization’ of North Korea — something that Mr. Kim has shown no willingness to accept in the past, and few believe he will accede to in the future.”

Such denuclearization would involve “the actual dismantlement of weapons, the removal of stockpiled uranium and plutonium bomb fuel from the country and a verification program that will be one of the most complex in history, given the vastness of North Korea’s mountains.” Furthermore, Trump has suggested that the North Koreans will gain nothing in return for this one-sided destruction of their defenses, until the process is all-but-complete; as one Trump official told the Wall Street Journal, “When the president says that he will not make the mistakes of the past, that means the U.S. will not be making substantial concessions, such as lifting sanctions, until North Korea has substantially dismantled its nuclear programs”.

In other words - give up your leverage first; then we’ll see. What Trump appears to seek is nothing less than a completely disarmed Korea that will pave the way for the “Libya solution” his people have openly suggested is the goal.

Obviously, North Korea will not go for that. The whole point of their nuclear program has been to ensure that their country avoids the fate of Iraq or Libya; which is why the intelligence community is generally united in their view that it will never be given up. According to Ryan Hass of the Brookings Institution, “virtually no North Korea analyst inside or outside of the US government expect Kim Jong-un to relinquish his nuclear weapons”, quoting former CIA analyst Jung Pak that Kim views nuclear weapons as both “vital to the security of his regime and his legitimacy as leader of North Korea”.

Meanwhile, the New York Times comments: “ask the people who have seen past peace initiatives whether they think this one will work out any differently, and they have serious doubts that Mr. Kim will give up his nuclear program for any price”, whilst for Stratfor, the complete denuclearization of North Korea is “a lofty goal that will be nearly impossible to ensure”.

So what is Trump doing? Surely he knows what he is proposing would be completely unacceptable to any North Korean leader, let alone Kim Jong-un?

But maybe this is the point. What if Trump, far from wanting to reach a deal, is actually deliberately pushing a proposal which is supposed to be rejected? After all, so long as he ensures his demands are unacceptable, he can offer the moon in return: recognition, technology, aid, lifting of sanctions, hell - why not? - even the removal of US troops from South Korea. Having such an offer rejected would allow Trump much more readily to be able to paint North Korea as the aggressor - unwilling to compromise, insincere in its desire for peace, etc, etc.

This is, after all, a time-honored tactic.

In February 1999, in the French town of Rambouillet, a series of meetings were convened between representatives of Kosovo’s multiethnic population and the US with the ostensible aim of resolving the conflict between Kosovan separatists and the Yugoslav government. For its part, the Yugoslavs had proposed a ceasefire, peace talks, the return of displaced citizens, and the establishment of a devolved assembly for the province, with a wide degree of autonomy.

This would clearly have gone a long way to addressing the conflict; but that very fact made it completely unacceptable to the US, desperate to justify their coming onslaught against Yugoslavia. Instead, they needed a ‘peace deal’ that would be rejected by the Yugoslavs, who could then be painted as the aggressors, paving the way for war. To this end, the ‘Rambouillet Peace Agreement’ was formulated. The document demanded complete de facto independence for Kosovo, whilst still allowing the province to influence the rest of Yugoslavia by continuing to send representatives to its federal institutions. Yet, just in case even this one-sided arrangement was accepted by the Yugoslavs, in chapter seven of the agreement, the US inserted a crucial clause: that NATO “personnel shall enjoy . . . with their vehicles, vessels, aircraft and equipment, free and unrestricted passage and unimpeded access throughout the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, including associated airspace and territorial waters”, whilst at the same time being "immune from all legal process, whether civil, administrative or criminal, [and] under all circumstances and at all times, immune from [all laws] governing any criminal or disciplinary offences which may be committed by Nato personnel in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia”.

In other words, Yugoslavia would have to not only submit to a full-scale occupation by NATO, but also give the occupiers the absolute and unaccountable right to abuse the population at will. Such a demand could never have been accepted by any sovereign country. But that, of course, was the point: this was an agreement penned precisely to be rejected, in order to paint the Serbs as the unreasoning aggressors. It worked perfectly: the ‘agreement’ was duly rejected, and the planned blitzkrieg of Yugoslavia followed, with 78 days of unrelenting aerial bombardment.

The same ruse was repeated the following year by US President Bill Clinton. At Palestinian-Israeli peace talks at Camp David, he made a proposal for a ‘final settlement’ of the conflict which allowed Israel to keep 80 percent of their illegal settlements along with sovereignty over a patchwork of roads linking them together and thereby cutting the West Bank into unviable bantustans - with refugees permanently denied the right to return to their homes in Israel. As former US president Jimmy Carter commented, “There was no possibility that any Palestinian leader could accept such terms and survive - but official statements from Washington and Jerusalem were successful in placing the entire onus for failure on Yasir Arafat”.

Indeed, through the distortions of Western media, a narrative emerged that Israeli President Ehud Barak himself had made this so-called ‘generous offer’, the spurning of which demonstrated the Palestinians hatred for peace and unwillingness to settle for anything less than driving the Jews into the sea. In fact, the Israeli side themselves had never accepted Clinton’s proposal, and had issued twenty pages of concerns they had with it. On the last of the Clinton-chaired meetings - the one from which Barak’s supposed offer emerged, held in Taba in 2001 - Barak later said that “it was plain to me that there was no chance of reaching a settlement… Therefore I said there would be no negotiations and there would be no delegation and there would be no official discussions and no documentation”. Nevertheless, the official narrative, to this day, recalls that the Palestinians rejected the Israelis’ ‘generous offer’ - and therefore only have themselves to blame for their continued slaughter.

The EU set up Yanukovych in the same way. In 2008, the EU and Ukraine agreed to negotiate what was supposed to be a trade agreement. Five years in the making, the EU Association Agreement was finally unveiled in 2013. But by then, the EU had included a clause on defense cooperation with the EU, effectively turning the country into an unofficial NATO member. Such a measure was guaranteed - and designed - to tear apart a country like Ukraine, a multiethnic polity with deep and historic ties to both Russia and Europe, whose unity rested on strict adherence to a policy of neutrality in terms of East-West rivalries. Furthermore, Yanokovych had an explicit democratic mandate for such neutrality, having been elected on precisely this basis. The Association agreement was duly rejected, as it was presumably intended to be - setting the stage for the Western-backed ‘Maidan coup’ and civil war which followed and continues to this day.

So Western governments certainly have form in crafting proposals designed to be rejected, in order to justify escalation. And the US has every reason for doing so with North Korea today.

Trump’s North Korea policy throughout last year was one of warmongering rhetoric and the ratcheting up of tensions. Whilst this was to some extent successful in bullying China and others into agreeing to harsher sanctions, this ‘consensus’ began to fall apart as Trump’s team stepped up their war talk at the end of the year, with defense secretary Mattis warning of “storm clouds...gathering” and national security advisor McMaster claiming that the odds of war were “increasing every day”.

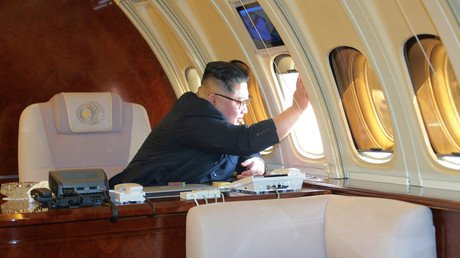

This ramping up of tension did not go down well in either Korea, and rapid moves to de-escalate were undertaken, with North Korean involvement in the winter Olympics a symbolic, but important, signifier of greater North-South cooperation to come. Then, in his New Year address, Kim Jong-un began a diplomatic charm offensive with the South which gained rapid results. A summit was set up between the leaders of the two Koreas, which eventually took place in April when Kim Jong-un became the first North Korean leader to cross the border into the South since the Korean war. The summit agreed to pursue denuclearization of the peninsula and to secure a formal Peace Treaty, with an outline peace arrangement to be reached by the end of the year.

This emerging detente between the two Koreas has hugely undermined Trump’s warmongering. In an article entitled “As Two Koreas Talk Peace, Trump’s Bargaining Chips Slip Away”, Mark Landler pointed out that “the talk of peace is likely to weaken the two levers that Mr. Trump used to pressure Mr. Kim… A resumption of regular diplomatic exchanges between the two Koreas, analysts said, will inevitably erode the crippling economic sanctions against the North, while Mr. Trump will find it hard to threaten military action against a country that is extending an olive branch”. Landler went on to quote Jeffrey A. Bader, a former Asia advisor to Barack Obama, that, following the North-South rapprochement, said “It becomes awfully hard for Trump to return to the locked-and-loaded, ‘fire and fury’ phase of the relationship”. Worse, “Inside the White House, some worry that Mr. Kim will use promises of peace to peel South Korea away from the United States and blunt efforts to force him to give up his nuclear weapons”.

Trump, therefore, urgently needs to snuff out this rapprochement if he is to return to the bellicosity that marked his Korea policy hitherto. As Landler wrote, “Mr Kim...made a bold bet on diplomacy” - and Trump needs to ensure that it fails. The best way of doing so is by putting himself at the head of it.

If Trump is indeed planning to use the Rambouillet ruse to reignite tensions against the North, it is important that he spin his designed-to-be-rejected offer as somehow incredibly generous. And in recent weeks there have indeed been moves in that direction.

First of all, Trump has appeared to accept that denuclearization might not need to happen in one fell swoop, telling reporters that whilst “It would certainly be better if it were all in one…. I don’t think I want to totally commit myself.” Next, Trump went out of his way to guarantee Mr. Kim’s safety. “He will be safe. He will be happy. His country will be rich,” the president said. You can already imagine Trump’s words when his ‘generous offer’ gets rejected: “we offered him security. We offered him prosperity. We offered him phased elimination. And he rejected all of it”.

Fascinatingly, it turns out that Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton has actually already suggested precisely the Rambouillet ruse. According to the New York Times, “Two weeks before he was recruited as national security adviser, [Bolton] said a meeting between Mr. Trump and Mr. Kim was useful only because it would inevitably fail, and then the United States could move swiftly on to the next phase — presumably a military confrontation… ‘It could be a long and unproductive meeting, or it could be a short and unproductive meeting," he said on Fox News.

Even among officials who worry about war, there is sympathy for his view that “failing quickly” would be valuable. Meanwhile, Stratfor’s analysis of the likely prospects for the forthcoming summit concluded that “it may also reinforce the idea that if the two leaders can’t negotiate a way out of the conflict, then perhaps a diplomatic solution isn’t possible and talk of a military solution to the United States’ North Korea problem could return...Without some change, we’ll probably find ourselves back on the path to containment, if not on a course toward military action to end the North Korean nuclear and missile program once and for all”.

Whether military action is realistically possible against North Korea, however, remains a serious question. Most analysts agree that the fallout from any retaliation - both against the 28,000 US soldiers stationed in South Korea, and against US allies in Seoul and Kyoto - would be unacceptably high. James Stavridis, former NATO Supreme Allied Commander, is typical in his view that there are “no military options which would result in fewer than several hundred thousand casualties and perhaps as many as 2m to 3m”.

So if war is not on the cards, to what end would Trump seek the rejection of his offer?

One answer has already been suggested - to scupper the emerging North-South co-operation that threatens to erode US influence on the peninsula. Summit failure would give Trump a perceived ‘moral right’ to bully the South into ending its outreach and returning to the US position of isolating the North.

But another reason could lie in Trump’s trade war with China, the opening shots of which have only just been fired. Any supposed North Korean intransigence could provide Trump with cover for initiating secondary sanctions against North Korea’s supposed ‘allies’. Congressional law already allows Trump to initiate secondary sanctions against anyone trading with the victim of primary sanctions, but with the current atmosphere of rapprochement, it is difficult for Trump to justify using these against China at present.

A North Korean ‘walk-out’ would provide the perfect excuse for stepping up economic warfare against China under the guise of sanctioning Korea. Indeed, Trump has already been setting up China as a potential scapegoat for any failure to reach a deal, claiming that Kim’s position had hardened following his meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping. “There was a different attitude by the North Korean folks after that meeting,” Trump told reporters recently, “I can’t say that I’m happy about it.”

The entire trajectory of Trump is, after all, not one of conciliation, but of escalation - on all fronts. Escalation against immigrants, against the working class, against Iran, against China, and even against his supposed chums in Moscow. There is absolutely no reason to think that North Korea is some kind of magical exception to this golden rule.

Setting up a deal guaranteed to be rejected, but which can be spun as incredibly generous, is, of course, no mean feat. This is especially true given that Kim has now repeatedly stated that he is willing to give up his nuclear weapons. Indeed, this possibility cannot be entirely ruled out: after all, North Korea’s conventional capacity alone - not to mention its mutual defense treaty with China - arguably provides as much deterrence as is necessary to prevent an invasion, as those casualty figures quoted above bear out. In this case, the devil will be in the detail - and more specifically in the timings of the granting of concessions. Trump is likely, in my view, to offer what appear to be very generous concessions, but make them contingent on unacceptably obtrusive verification measures or unachievable levels of ‘proof’ before any of them kick in. Perhaps they will just copy and paste chapter seven of the Rambouillet Agreement in its entirety. A secret clause demanding NATO occupation of all of North Korea would probably do the trick.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.