Kirkuk to Dunkirk: Kurdish journalist fights to stay in UK after fleeing assassins (RT EXCLUSIVE)

A Kurdish journalist is fighting for UK asylum after serving with American forces in Iraq, narrowly escaping assassination for his reporting, being labeled a torturer by US immigration, and entering Britain illegally smuggled inside a lorry, RT has found.

Aram Fareeq Abduljabbar, 32, arrived at the Grande-Synthe refugee camp in Dunkirk, northern France, on January 25 before crossing into Britain concealed in a lorry on March 1. However, his journey had begun six years earlier when he was targeted for his reporting while working for the Kurdistan Post.

On September 9, 2011, Aram says he narrowly escaped death when gunmen fired on him from a black BMW in the streets of Kirkuk in northern Iraq. The incident, which had come after repeated threats and intimidation, finally forced him to skip the border into Turkey.

“I don’t have a choice,” said Aram, speaking to RT in the Dunkirk camp in February. “My life is not safe in Iraq.”

After a stint in sheltered accommodation in Wakefield, Aram is now living in Bradford, northern England, awaiting a Home Office ruling on his case.

His story almost seems like a microcosm of the wider refugee crisis.

A vocation

Aram left school in 1995 and went to work at his father’s market stall, selling clothes and polishing shoes. Three of his paternal uncles had been killed by Saddam Hussein’s regime, he says, so supporting his family took priority over further study.

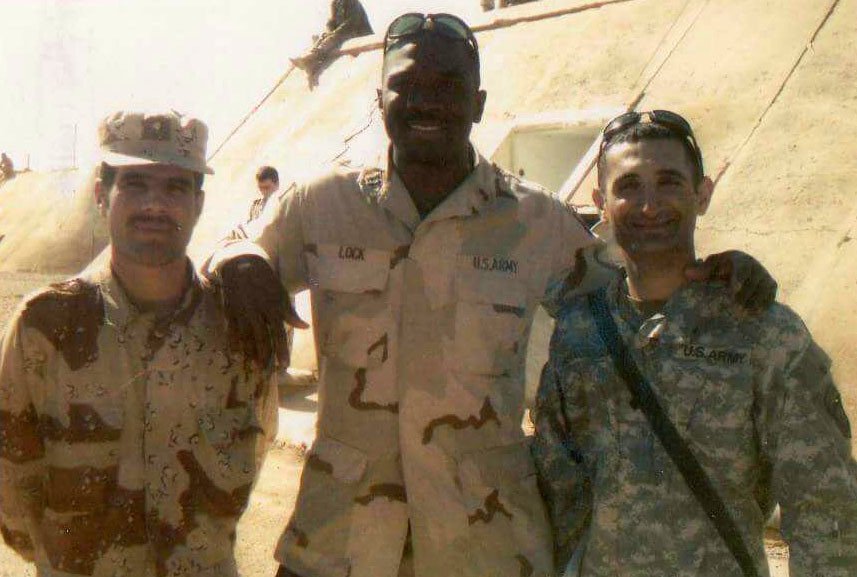

When he came of age in 2000, Aram joined the Kurdish armed forces, the Peshmerga, with whom he could earn extra money. When the US Army invaded northern Iraq and toppled Saddam in 2003, Aram’s brigade, 16 Sulemani Division 4, was amalgamated into the Iraqi National Guard.

Besides training Aram to man military checkpoints, the Americans also taught him and other Iraqi troops in their charge about human rights, including freedom of the press. It was this introduction that spurred Aram to become a journalist, which he took up while on fortnightly leave from his unit. Quitting the military in 2006, Aram began writing and broadcasting full time.

In 2010, he started work at the Kurdistan Post, where he took a particular interest in exposing corruption. However, the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) were not fond of the paper’s line, and his troubles soon began, Aram says.

Powerful enemies

The young reporter’s collaboration with US forces had already courted ill favor, making him a target of terrorist groups. Aram says he twice survived improvised explosive devices (IEDs) intended for him in Kirkuk, and now has difficulty hearing in his left ear.

Because his family had suffered so much under Saddam, Aram wanted to use his platform to highlight allegations against KDP President Masoud Barzani, who he accused of working with the Baathist regime to suppress Kurdish opposition.

By raising such awkward issues, Aram made some powerful and determined enemies.

Aram says he was attacked multiple times by KDP heavies because of his work. In 2009, he says he was set upon by thugs in Suleimani, who broke his nose. He was later stabbed near the Kurdish parliament in Erbil.

In Iraq, journalist Sardasht Osman abducted, killed. Wrote on corruption. #EndImpunity#IDEIhttp://t.co/goYLAvh3bhpic.twitter.com/nrwTJdXNdL

— CPJ (@pressfreedom) October 28, 2014

Human rights groups say the KDP had Aram’s friend and fellow journalist Sardasht Osman abducted and killed in 2010. They also claim party militants gunned down Soran Mama Hama, also a reporter, in 2008. Kawa Garmyane, another of Aram’s friends, was killed in the city of Kalar in 2013 before he could publish corruption allegations, this time by suspected PUK assassins.

By that time, Aram had already left the country.

‘Leave or die’

One day in 2011, the phone calls started.

“By telephone some terrorist every day, every day call me, ‘I kill you, you need to stop the b******t… I kill you like Sardasht Osman,’” Aram told RT.

The caller, who spoke in Kurdish but dialed from a Fallujah area code, told Aram he must stop reporting on the KDP and Barzani, and that he must leave the country or be killed.

Taking the threats seriously, Aram went to the police.

Kirkuk’s police authority is suspected of having close ties with the political establishment – particularly the PUK. Officers at first dismissed the phone calls as a practical joke, but later made it clear that Aram should not be reporting on the affairs of the KDP and PUK. Aram was on his own.

On September 9, the assassins struck.

Aram was on his way to Tuz Khurmatu just south of Kirkuk when a group of men in a black BMW opened fire.

Although Aram escaped without injury, he was convinced that he would die if he stayed in Iraq, so he left his job and family and set out on a journey that would eventually bring him to Britain.

No shelter

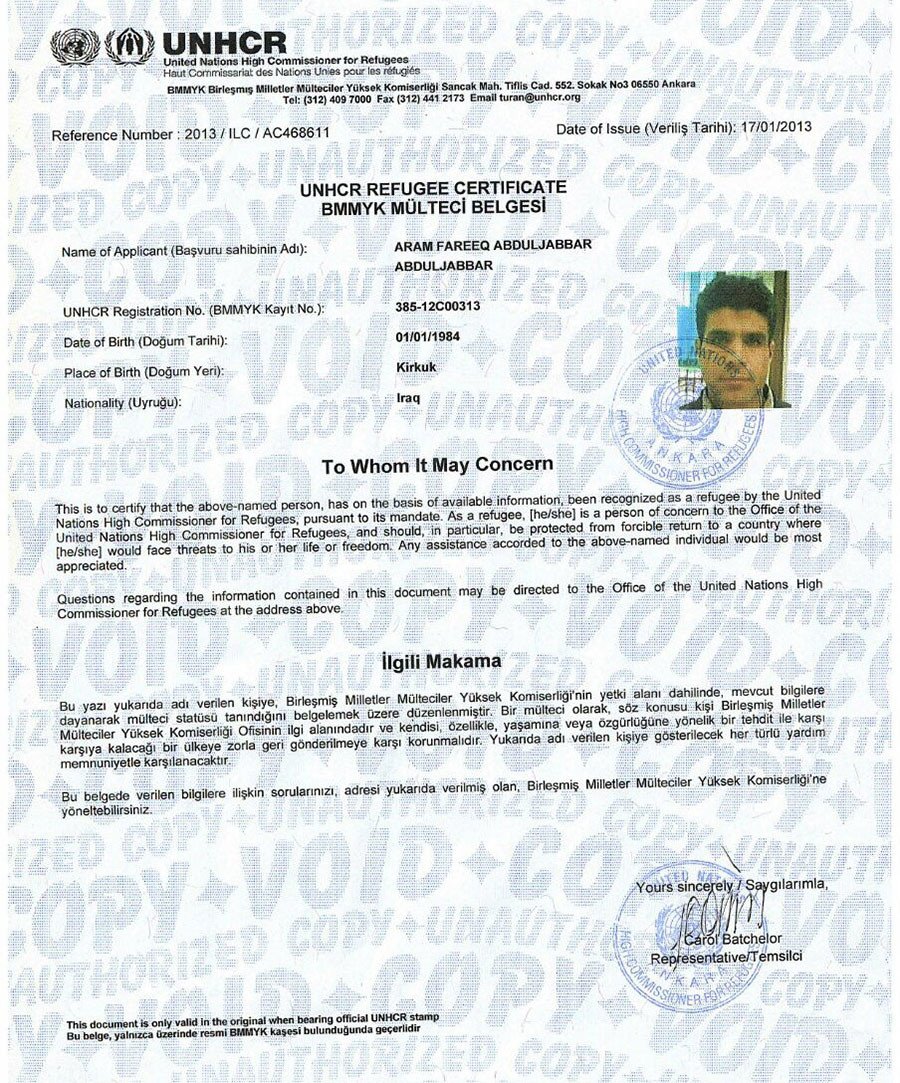

Aram made contact with the UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, which sent him to Kayseri, deep in the heart of Turkey, where he soon found himself unable to earn a proper living and in squalid conditions.

He applied for refugee status at the end of January 2012, but it would be a full year before he received his official documentation.

Desperate to secure asylum, he reached out for support from the media industry.

“Aram contacted us back in 2013,” said Monir Zaarour, Middle East and Arab World Co-coordinator for the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

“He sent us details of his case, but we were unable to verify the details of his story, as we rely mainly on our affiliates in the ground.

“I believe he didn’t report the threats he received to the Kurdistan Journalists’ Syndicate before he left the region to Turkey. However, we sent a letter on his behalf to the UNHCR in Turkey to support his case,” Monir noted, while saying that Aram’s account is entirely believable.

“Iraq remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, including the Kurdistan Region of Iraq,” he said, noting that “several journalists have been assassinated in the last few years in the region because of their critical reporting.”

British Home Office guidance on humanitarian protection defines the threat of “unlawful killing” as “where there is a real risk that a person would be unlawfully, that is extra-judicially, killed by the state (or agents of the state), or there is a real risk of targeted assassination by non-state agents and there is no effective protection and no feasible internal flight alternative.”

Aram’s asylum case appeared to be open and shut, but a red flag suddenly appeared.

Accused of torture

Having worked closely with the Americans during the Iraq occupation, Aram felt he stood a good chance of being granted asylum in the US, so he traveled to Istanbul to meet with the International Catholic Migration Commission (ICMC) to discuss his eligibility.

He was rejected.

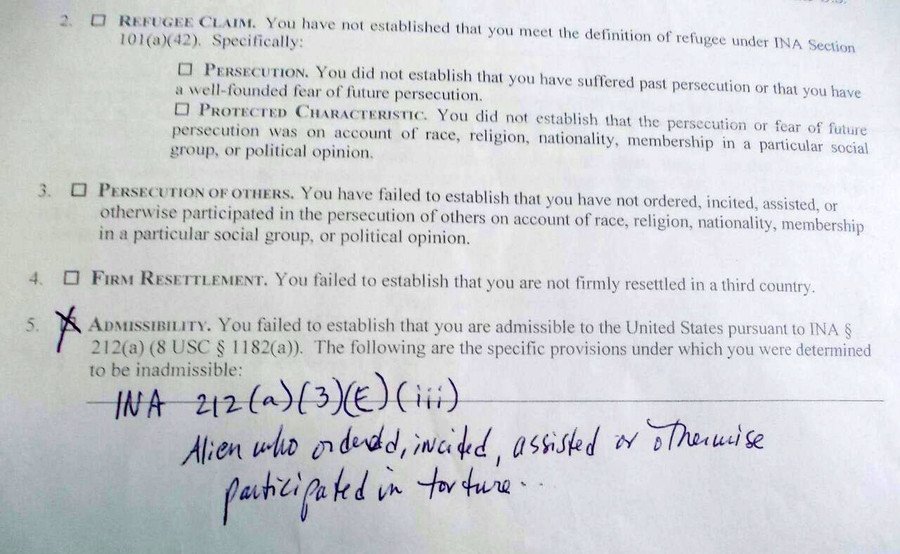

On June 17, 2013, US Citizenship and Immigration Services said Aram was not admissible under provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) because, it stated, he is an “alien who ordered, incited, assisted or otherwise participated in torture.”

Aram denies the allegation, insisting that he had been misinterpreted during the screening interview. While he admits that, as a journalist, he witnessed the Iraqi army committing acts of torture, he insists that he did not participate.

RT has been unable to independently verify Aram’s story.

Accepting that there may have been a translation issue, Aram was told he should wait for a review, when he could better explain his case. However, frustrated by the delay, he took his case back to the UNHCR to try for asylum elsewhere.

After years of waiting while living precariously, the UNHCR finally told Aram he would not be given asylum in Turkey.

After this setback, Aram’s Iraqi friends urged him to leave Turkey and loaned him money for his journey onward. On January 8, 2017, six years after his ordeal had begun, Aram paid a group of smugglers to take him to Italy.

He crossed the sea in a small boat with several other families, all taking the same uncertain leap from one unwelcoming continent to another.

Illegal entrant clandestine

Aram was fingerprinted by Italian police on January 14. After several failed attempts to cross into France, he paid a smuggler €600 to spring him across the Italian border. From Nice, he traveled to Paris and, from there, he arrived in Dunkirk on January 25.

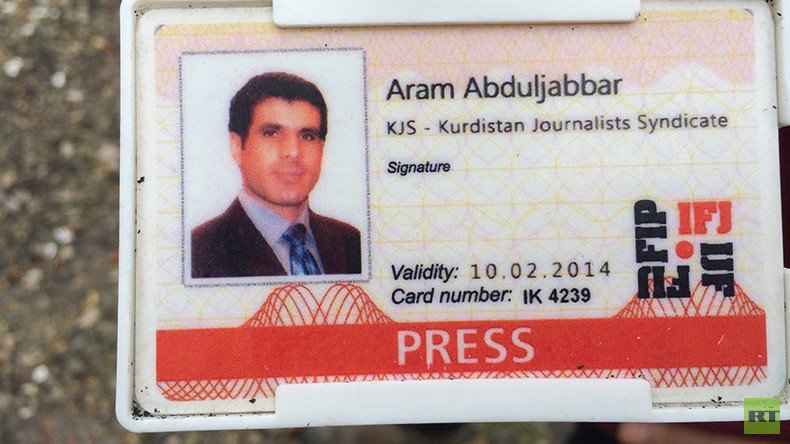

It was here that RT met Aram, carrying his expired IFJ press card and eager to share his story on February 7.

Some weeks later, on the brink of giving up, Aram crossed the English Channel concealed inside a lorry with the help of smugglers and set foot in London for the first time on March 1.

As an ‘Illegal Entrant Clandestine’, the British Home Office considered Aram “liable to detention” and sent him to Wakefield’s special Initial Accommodation center, Angel Lodge, where he lived under curfew, banned from leaving town under the watch of private security giant G4S.

He was soon moved into the community in Bradford, where he now awaits his asylum ruling.

Contacted by RT, a Home Office spokesman said: “We do not comment on individual cases, but judge every case on its individual merits.”