One country, many wars: Social media study exposes divisions among Syrian opposition

A study of more than 1.7 million tweets on the Syrian conflict shows that hostilities are not between two sides, but rather between many factions - each with their own agenda and ideals.

Derek O’Callaghan of University College Dublin led an international team of researchers who studied more than 600 of the most popular accounts reporting about the war on Twitter, and over 14,000 channels on YouTube.

The study’s authors stated they expected to find two parties involved in the conflict, each becoming more radicalized since the start of the study period in 2011. They said they expected to draw parallels between the two sides and Republicans and Democrats in the US, as well as with Islamists and secularists in Egypt.

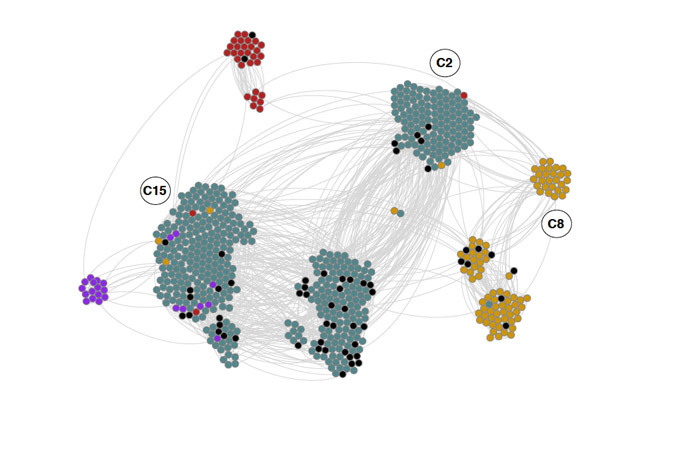

Instead, they found a “convoluted” picture of four distinct groups, each existing primarily in their bubble of shared links, posts, and images that matched their version of the war.

The two groups with the largest social media presence were the moderate opposition and the radical Islamists, followed by a much smaller output from accounts describing the war from the Kurdish minority’s perspective. The fourth most active group but smallest in number were those depicting the government’s view of the war.

The contrast between the content posted by these groups is illuminating.

Describing the Islamist feeds, the authors say that “photos tweeted by these accounts include many of weaponry and attacks, also close-ups of ‘martyred’ fighters and a small number of individuals holding up severed human heads.”

The vast majority of the posts in this group were made in Arabic and were consumed by a local or regional audience.

Much of the moderate opposition’s tweets were in English, aimed at a worldwide audience with the intention of stimulating international attention towards the conflict. The posters themselves often “appear to be members of the Syrian diaspora, identifying themselves as presently located not in Syria but elsewhere in the Middle East (e.g. Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, UAE), or in the US or Europe.”

Their coverage of even major Syrian stories differs wildly.

For instance, popular jihadi social media accounts did not post any videos referring to the August gas attacks in Damascus for two days, while the internationally-minded moderate opposition’s accounts uploaded 440 videos in the 24 hours after they occurred.

Though the rifts between various opposition groups have become more manifested as of late – including internecine fighting – studying these opposed platforms can still provide insight, particularly if outsiders use the content as a source to better gauge the mood in the country.

Meanwhile, the authors say they will perform “further analysis of these groups, with a view to monitoring the flux in group structure and ideology.”