Gender pay gap decreases… for all the wrong reasons

The gap in pay between men and women is closing, but not because women are earning more. Men are earning comparatively less than they should due to stagnant wages and inequality is on the rise, according to a new report.

Wages for the vast majority of American workers have remained stagnant since 1979, as pay has not kept pace with increased productivity. Combined with the continued wage gap, the stagnation has hit women harder than men, according to the latest report from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank focused on low- and middle-income workers.

“[W]age growth for women <strong>and</strong> men has failed to keep up with productivity gains in recent decades ‒ a trend that has done much to harm women’s wages,” the study’s authors, Alyssa Davis and Elise Gould wrote in their report, ‘Closing the Pay Gap and Beyond’. They noted that “gender wage parity does not improve women’s economic prospects to the greatest possible extent if wages for men and women remain equal but stagnant in the future,” adding, “Wage growth is a women’s issue.”

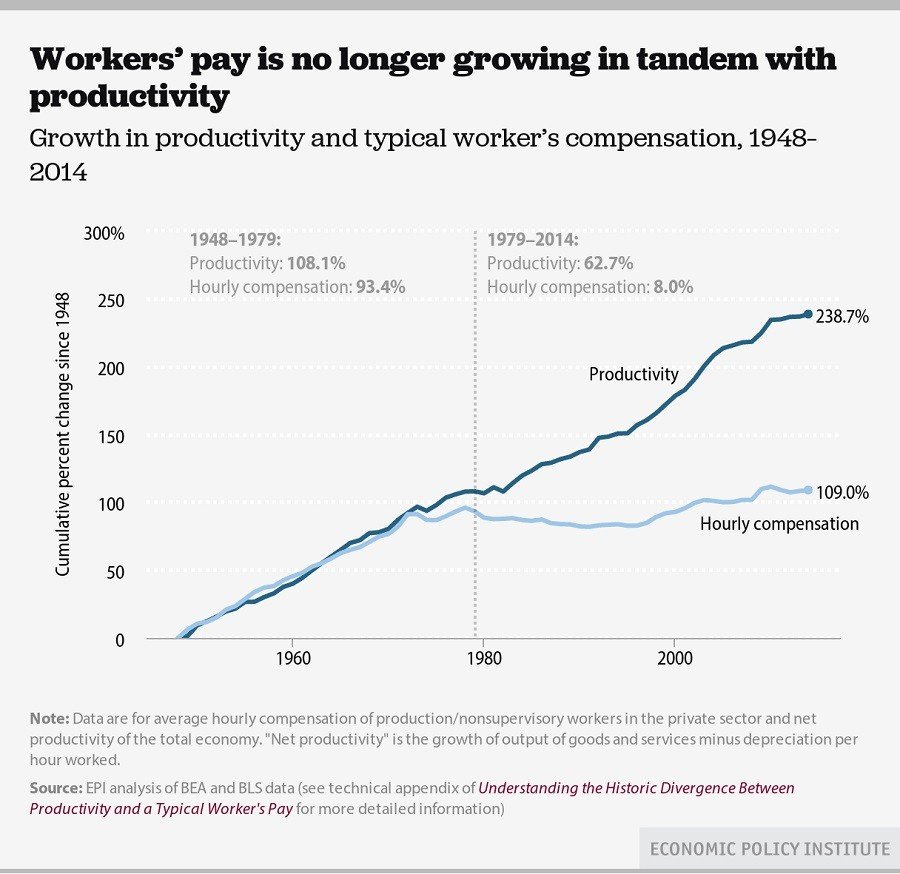

The gap between compensation and productivity began rapidly increasing around 1979, after rising roughly in tandem between 1948 and the mid-1970s, according to the report. Since then, productivity has risen consistently, though at a slightly lower rate than before, a total of 62.7 percent, while hourly compensation grew only 8 percent over that same time period.

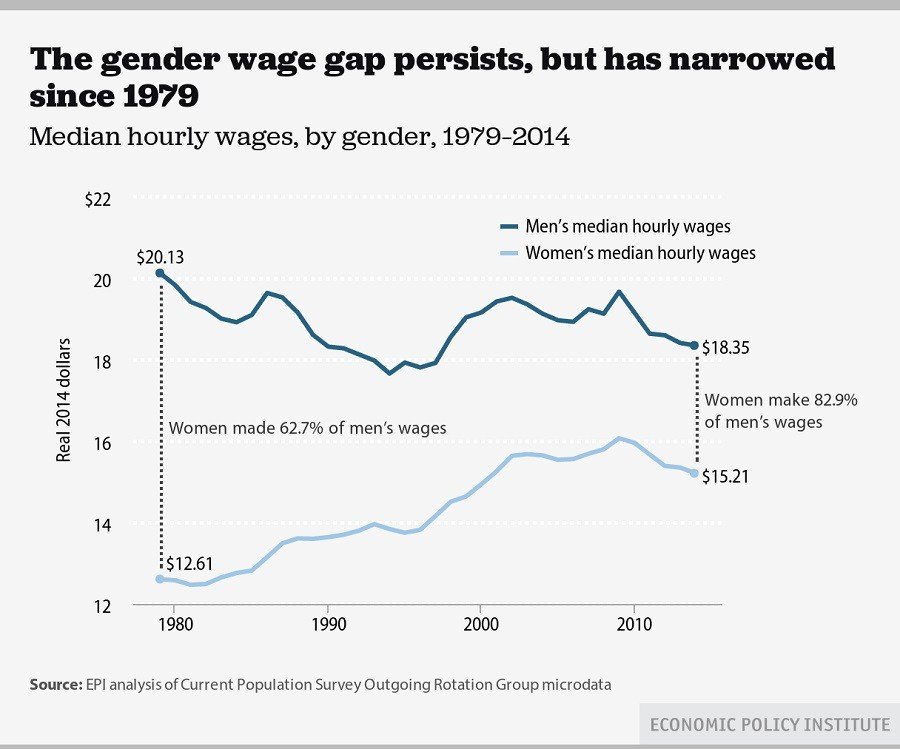

“About 40 percent of the progress made in closing the wage gap since 1979 was due to men’s wages declining in an era of increasing inequality,” the authors wrote. “Remedying unfairness of pay for women is necessary, but wage parity gained simply because male wages dropped is no cause for celebration.”

In 2014, the hourly wage of the median woman ($15.21) was 82.9 percent that of the median man ($18.35), they found. They noted that gaps occur regardless of wage percentile, race and ethnicity, or educational attainment

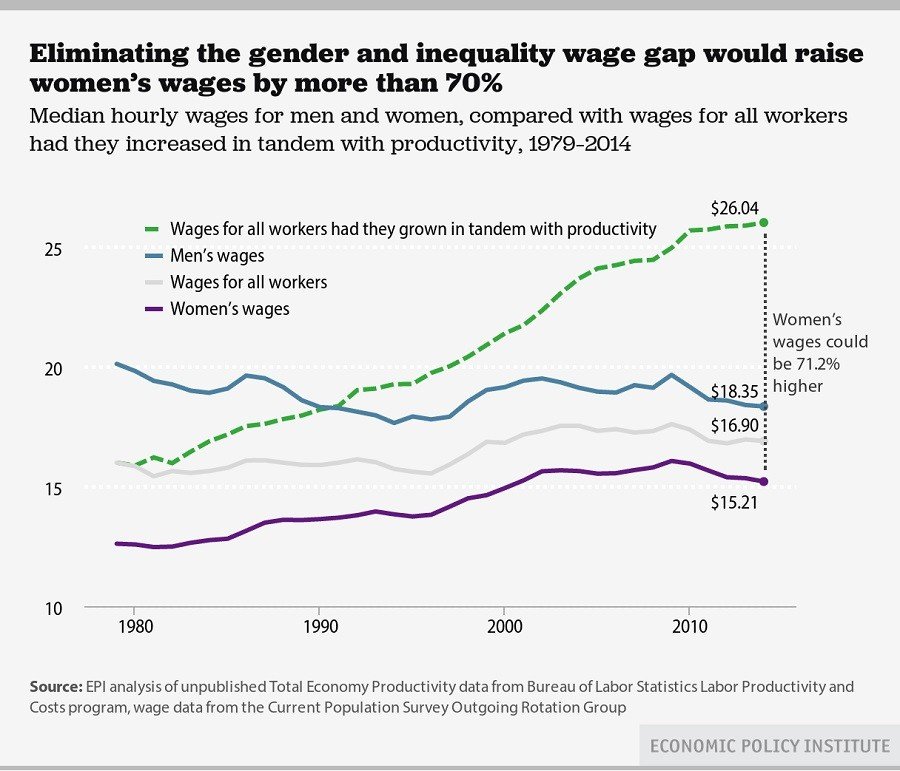

“If we had closed the gender wage gap and had inequality not increased over 1979–2014 (i.e., had wages grown in line with productivity), the hourly wages of the median woman could be over 70 percent higher today ‒ $26.04 instead of $15.21,” Davis and Gould wrote.

Nearly half of the disparity between what women should be earning if there was no pay gap and what they are earning is due to overall inequality from stagnant wages, or about $5.32 of the missing $10.83. Another 16 percent ($1.69) of the disparity is explained by gender inequality, while the remainder ‒ 35.3 percent or $3.82 an hour ‒ is due to the compounded effects of closing these two gaps together, the study found.

The report’s authors offered several pie-in-the-sky recommendations for ending discriminatory practices contributing to gender and race inequalities, and for boosting the bargaining power of low- and moderate-wage workers. Their general suggestions for ending inequalities included changing the culture of work to value work–life balance, deterring the segregation of genders into specific occupations, requiring more transparency in compensation data, and addressing the distribution of unpaid care work in the household by making it easier and more affordable for both men and women to spend more time at home.

To increase the workers’ bargaining power, Davis and Gould advised raising the minimum wage, especially for tipped workers, so they could achieve parity with the regular minimum wage; providing earned sick and paid family leave; and updating labor standards to raise the salary threshold for earning overtime, to crack down on harmful practices like wage theft and to regularize work schedules.

Although the the EPI report shows that the gender pay gap is most notable among top earners, a report released by PayScale in early November shows that the controlled pay gap ‒ an "apples-to-apples" analysis of men and women working the same jobs and controlling for factors such as experience, location, hours worked, education and more ‒ is a mere 2.7 percent, meaning women earn 97.3 cents to a dollar earned by a man with a similar background in a similar position. The median male pay is $62,000, versus $58,600 for women. Yet the two reports agree that the pay gap widens closer to the top of the corporate ladder.

Looking at the uncontrolled pay gap ‒ a straight comparison of all male and female wages ‒ women actually perform worse than the oft-cited 78 cents on the dollar statistic. PayScale found that women earn 25.6 percent less than men ‒ 74 cents on the dollar ‒ with the male median pay being $60,200, while the median pay for females is $44,800.

PayScale analyzed more than 1.4 million salary profiles to reach its conclusions about the much smaller controlled pay gap.