NIH failed to notify employees about smallpox discovery, despite promises to be more open

Employees at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. learned about the discovery of decades-old smallpox vials from news reports – not their employer. It marks the second time in three years that NIH has stayed mum on potential public risks.

Only July 1, employees found a box of vials in boxes that appear to be from the 1950s when they were cleaning out an unused laboratory storage room in preparation to move the lab over to the Food and Drug Administration’s main campus in nearby Silver Spring. The current lab has been operated by the FDA since 1972.

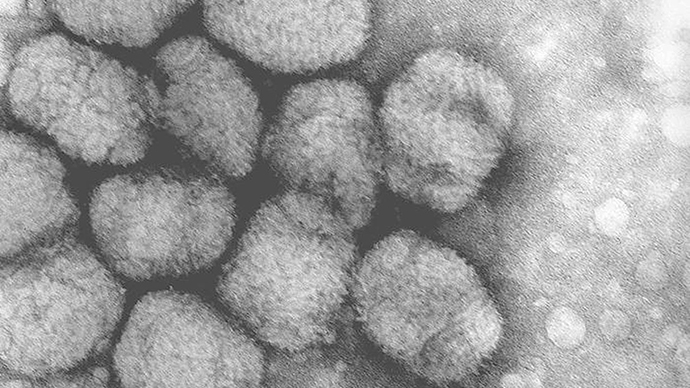

Of the 16 freeze-dried vials, six were labeled as containing variola, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says is “the severe and most common form of smallpox.” The labels on the other 10 vials were unclear as to what they contained.

On Monday, the CDC arrived at the NIH campus to remove the specimens to their high-containment facility in Atlanta, where overnight testing in the Biosafety Level-4 (BSL-4) Lab confirmed the presence of smallpox. The Georgia-based agency is currently performing additional testing to discover whether the materials inside the vials are viable. This testing could take up to two weeks, the CDC said in a Tuesday statement.

That statement, which was made over a week after the smallpox vials were found, created a news frenzy. Also on Tuesday, NIH posted on its blog for employees to sign up for AlertNIH, a managed communications service that allows employees and contractors to receive emergency information on both personal and government devices.

AlertNIH was not used at any point to alert the agency’s 18,000 Bethesda-based employees to the presence of smallpox at the sprawling campus.

They find smallpox in a building I go in at NIH and don't sent me an email. But they send me an email when there is a bear on campus.

— Ben Harris (@roboben12) July 9, 2014

A researcher told the Washington Post that employees should have been told, even though the CDC said there was no exposure risk to the public.

“I think the responsible thing to do would have been to inform us without us having to find out through the media,” said the researcher, who works at the clinical center on the main campus and did not want to be identified for fear of retaliation.

It's a bit freaky that I used to work in Building 29A at NIH where, according to the Washington post, the smallpox was found. Yikes!

— J.P. McWatters (@mcjiggs) July 9, 2014

An NIH spokeswoman told the Post that the agency did not notify employees because there was no risk to them.

Smallpox found in Maryland at the NIH, Obama spoke within 2000 ft. of it in 2009. #Obama#NIH#Smallpox#WHOhttp://t.co/YibJ0R0FCB

— Jimi Devine (@JimiDevine) July 9, 2014

The CDC notified its employees about the arrival of the smallpox vials via email midday on Tuesday.

“We’ve learned that you simply can’t overcommunicate when it comes to an event like this,” CDC spokesman Tom Skinner told the Post.

Nothing like learning I've had #smallpox next door! http://t.co/vXnsFRAwpq IMO, this says we should NOT destroy current samples. @marynmck

— Miriam E. Tucker (@MiriamETucker) July 9, 2014

NIH came under fire in 2012 for not immediately reporting a deadly superbug outbreak in 2011 to state and county officials or to the public, the Post reported. In that case, an antibiotic-resistant strain of the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae spread through the research facility starting in June 2011, infecting 18 patients by August of that year. Twelve of those patients died, and seven of those deaths were directly attributable to the bacteria.

The agency did not contact Maryland authorities until the situation worsened in December, when they asked the state epidemiologist for advice. But neither the state nor NIH shared that information with Montgomery County, where Bethesda is located, just outside Washington, DC.

The public was not informed until August 2012, when NIH researchers published a scientific paper about the superbug. In November of that year, the agency and state and local officials signed a pact that NIH will notify the county of rare or potentially high-profile diseases or outbreaks that might alarm the public, even if there is no public health risk, Carol Jordan, the county health department’s director of communicable diseases and epidemiology, told the Post.

Although the outbreak “was probably not a risk to the public,” Jordan said that “nobody wanted a repeat of what happened during the Klebsiella outbreak over there.”

“This was a learning experience that we hadn’t had previously,” Montgomery County Council President Roger Berliner said to the Post about the superbug. “They are very open and willing to share with us at any point in time,” even in situations that pose only a “borderline” risk to public health, he said at the time.

But it now appears that the agency may not have learned its lesson after all.

Sure #glad#NIH is now searching their campus, given the 16 #smallpox vials left lying around. Hubs goes there weekly to play chess (1/2)

— Diane McIntire Rose (@sistrum42) July 9, 2014