Russia or Brussels? Foreign policy becomes key battleground in Moldova's presidential election

Moldova heads to the polls on Sunday for the second-round of its presidential election. But, while voters focus on the country's coronavirus response and its faltering economy, ties with Russia are also a key topic for debate.

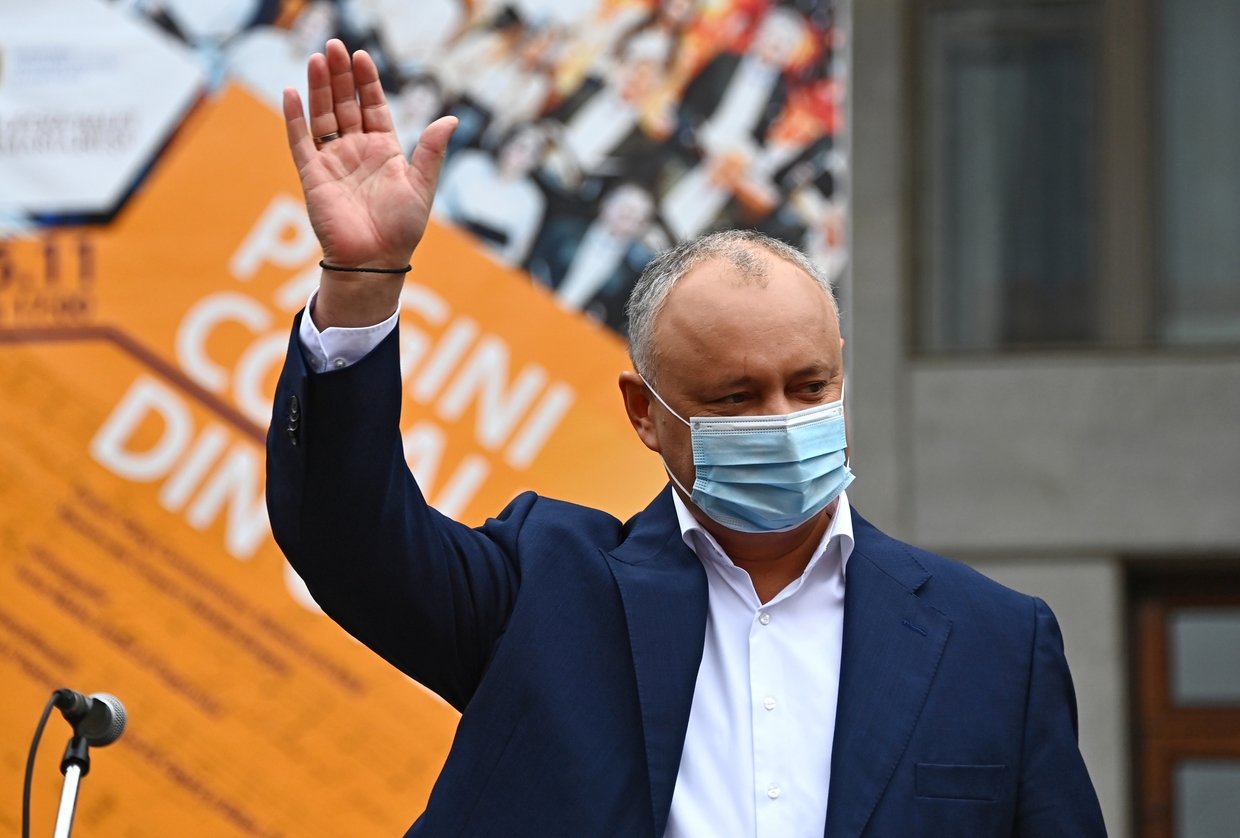

The incumbent, President Igor Dodon, is coming to the end of his first term in office and seeking re-election. The one-time Socialist Party leader faces a tough challenge from his liberal former prime minister and ex-coalition partner Maia Sandu, who topped the first round of voting with 36 percent of the vote. Dodon came in a close second with around one in three votes cast for him.

The former Soviet Republic, which borders Romania and Ukraine, is one of Europe's least popular destinations for tourists. However, it has attracted one high-profile visitor in Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has made multiple trips to the country in the name of building closer relations. In return, his counterpart, Dodon has visited Moscow dozens of times during his time in office, positioning himself as a close ally of the Kremlin.

Putin offered Dodon the same support in 2019, as his allies in the Socialist Party struggled to form a coalition government after hotly contested parliamentary elections ended in stalemate and plunged the country into a political crisis. The Russian president pledged to keep supporting in the Moldovan leader, "so that they eventually get rid of these [opposition parties] who – to put it mildly – usurped power… and, despite possible internal differences, find strength to build cooperation in the interests of Moldova and its people."

The situation was only resolved by the formation of an unlikely alliance between the historically 'pro-Russian' Socialists and the 'pro-EU' Party of Action and Solidarity, led by Sandu, who took on the role of prime minister under the terms of the agreement. Putin praised the arrangement for putting an end to the political turmoil, saying that "what President Dodon and his former opponents, from what can be called the pro-Western parties, have done now is a step towards building a capable, civilized and modern-day state."

Now standing to replace Dodon as president, Sandu has tapped into relations with Russia as a dividing issue for Moldovan voters. Her party continues to call for closer ties with countries like Germany and Poland, and portrays itself as supportive of Western-style social liberalism. Herself a former economist with the World Bank, she has pledged to seek financial support for the country from the European Union.

Dodon, by contrast, has called for an "equilibrium" to be maintained in relations with Moscow and Brussels, who he describes as Moldova's "foreign friends and partners." However, tensions over ties to Russia have created political problems for him in the past, and the president accused nominally pro-EU opposition parties, including Sandu's, of "provoking a crisis" in April by attempting to block a Kremlin-backed loan of more than $230 million to the country. He wrote on social media that "it is not the conditions that concern them, and not the details of the agreement, but the fact that Moldova will receive the money."

Also on rt.com Moldovan election: opposition candidate Maia Sandu leads first round, but incumbent Igor Dodon still in contentionMoldova's economy, already one of the poorest in Europe, has been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic and is dependent on support from abroad. A UN report in October predicted that the country's economy would contract by "6.7 per cent this year" with the pandemic having "disrupted every aspect of life."

Sandu has made the nation's ailing finances a key part of her campaign, claiming that "one third of Moldovan (businesses) are on the verge of bankruptcy because the current authorities haven't been helping the economy at all."

Corruption in Moldova also continues to be a major issue, and the Western state-funded Transparency International NGO reports that the country is among world leaders in illicit dealings, with one in five Moldovans paying a bribe for public services in the past year.

The fragile coalition government of socialists and liberals made progress on the issue, but eventually came to an impasse over processes for appointing top legal officials in a row that brought the agreement to an end.

In an interview with journalists last month, Sandu argued that diplomatic ties were suffering because of illicit dealings, saying that "relations with the EU and US have been going from bad to worse, because Igor Dodon has been trying to establish good relations only with Russia; but even with Russia, he has been using this for his personal interests; not to solve the country's problems."

Dodon himself has lashed out at foreign influence, claiming that Moldovans living abroad, for example in Western Europe, and voting by post were "out of touch" with the needs of those still living in the country. Tallies show that around 70 percent of those voters had backed Sandu. He added that "we can say that the diaspora represents, in a real way, a parallel electorate for Moldova."

Transparency International, which receives millions of euros in grant funding from countries across Europe and the US, struck back at Dodon, reiterating allegations that his ties to Russia are for personal gain. Veaceslav Negruta, a Moldova-based analyst at the NGO, exclaimed "'Parallel electorate'? The lives and health of many people here at home depend on these people [in the diaspora]. They are constantly thinking about those back at home. They are better connected with their homes, with Moldova than a president who is serving foreign interests."

For its part, Moscow has expressed concern over political influence in the country. In October, the country's foreign intelligence service (SVR) warned of "preparations for the arrival in Moldova of a group of American 'colour revolution' specialists with political tasks."

Also on rt.com Autumn of discontent? Moldova is next US target for ‘color revolution’, Russia's chief spy warns ahead of presidential electionIf the vote on Sunday was to split across these lines, Dodon would likely emerge the winner. The candidates who placed third and fourth in the first round, Our Party's Renato Usatii and the Șor Party's Violeta Ivanov, are both broadly considered to be Eurosceptic and pro-Russian. Together, their vote share accounts for more than 20 percent – the whole margin of victory.

However, while Moldova's politicians might see economic and political opportunities in positioning themselves as pro-West or pro-East, these labels seem unlikely to resonate at home. Notwithstanding how polls show that Moldovans are fairly evenly split in their support for Brussels and Moscow, low pay and corruption are more likely to concentrate the minds of voters, one in five of whom live below the poverty line. Most Moldovans may not have geopolitics at the front of their minds when they vote on Sunday, but the election will undoubtedly be watched closely by those in Moscow and Brussels, as the future of one of Europe's poorest nations is decided.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!