If Canada wins a seat on the UN Security Council now, it’s just another vote for Washington

If Canada’s current foreign policy is any indication, should it win a UN Security Council seat on Wednesday, it would more likely buttress the positions of Washington than to pursue independent, let alone principled positions.

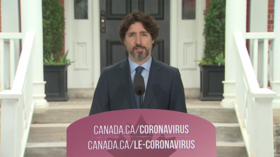

When Canada's largest online news siteasked readers whether they support Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s efforts to get a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council (UNSC) or not, it should have probably been little more than a formality.

Not only does the Toronto Star often reflect the positions of the Liberal Party, but its readership tends to lean to the Center and hold the sort of values that align with the UN mission as well as with Canada’s projected image as a sort of international ‘good neighbor.’

Surprisingly, however, patrons weren’t convinced with the idea that “Canada deserves a seat on the UNSC.”

A recent reader poll in the Toronto Star asks whether Canada deserves a seat on the U.N. Security Council.The answer is a resounding 'no'.I agree.#humanrights#cdnpolipic.twitter.com/kMSxsk4hEe

— Dimitri Lascaris (@dimitrilascaris) June 6, 2020

Though it certainly wasn’t a scientific poll, it is still indicative of the aversion that many have towards the bid, and for a variety of reasons.

Media on the Right has snubbed the government’s campaign on grounds like the declining representation in peacekeeping missions, as well as criticisms of the Liberals’ handling of the Covid-19 outbreak and immigration policy. Others have resorted to inflammatory gripes regarding Trudeau’s bid to secure the support of African nations, with the Globe and Mail’s Robert Fifie accusing the Canadian leader of “buying off African dictators.”

Despite having spent the better part of four years campaigning, Trudeau is having an increasingly hard time making the case, in and out of the country, that Canada can be a value added on this body.

Canada has been elected to the Security Council on six occasions since 1947, but not in the last two decades. Under the Liberal government of Jean Chretien, Canada received 75 percent of the vote in the first round to secure a position for the 1999-2000 term.

For decades, both Liberals and Conservatives governments were successful in convincing their international counterparts that Canada would be a “responsible, competent, moderate middle power,” a voice that would promote multilateralism on a stage built to uphold the status of the post-war superpowers. Former Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau pushed for a review of the pros and cons of having a seat, and ultimately decided on pursuing the post even though it might “oblige the government occasionally to take public positions on issues which might not be popular” with the electorate.

But this Trudeau doesn’t do things like his father did, and neither is Canada the same actor that it used to be.

If Canada’s current foreign policy is anything to go by, its votes in the Council will likely just add weight to whatever Washington is pushing for, not any independent, principled position.

This is especially true when looking at Latin America and the Caribbean, where Canada has played a leading role in the US-led attempts to unseat Venezuela’s government, including stewarding the so-called Lima group, while at the same time maintaining ambiguous positions around the dubious elections in Honduras and Brazil, and tacitly supporting the coup in Bolivia. The country also had little to say about the violent suppression of protesters in that country as well as in Ecuador, Chile or Haiti, who are all currently led by US-backed leaders.

Outside of the region Canada has displayed this same tendency, including acting as a proxy for the United States in its saber-rattling towards China by arresting Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou.

Canadian troops also make up over one-third of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s 1,400 strong ‘deterrence mission’ in Latvia, while sending just 41 troops to UN peacekeeping missions.

Ottawa has also gone to extraordinary lengths to bolster arms sales to Saudi Arabia, including using $650 million of taxpayer money to back the production of combat vehicles so the Kingdom can continue to starve and massacre Yemenis.

Canada wants a seat on UN Security Council. Also Canada:- Sends billions in arms to Saudi Arabia- Trudeau signed off on $14 billion in light armored vehicles to Saudi Arabia calling it a "stabilizing force"- sniper rifles & light armored vehicles used in conflict in Yemen pic.twitter.com/91RSfISdPL

— Camila (@camilateleSUR) May 26, 2020

It is because of this sordid foreign policy record, as well as criticisms of duplicity when it comes to climate change, that the Left in Canada has also joined the chorus who say the country shouldn’t have a seat at that table.

“Canada is not acting as a benevolent player on the international stage,” reads a petition signed by the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute, which has garnered the signatures of over 3000 individuals and organizations, including national unions, current and former lawmakers and renowned activist David Suzuki.

Even in the years before the current administration, Canada's positions in the global arena were increasingly being shaped by the commercial interests of Canadian companies and the geopolitical imperatives of Washington. This was seen as one of the reasons why Canada was looked over for the UNSC during Stephen Harper’s Conservative government.

Trudeau promised a return to the Canada outlined by his father but, by all accounts, he has failed to deliver. The other two contenders for the seat, Ireland and Norway, have not only been better at meeting their obligations to this organization, but have also shown willingness to take positions that don’t just echo those of the power-brokers.

The international situation is delicate, to put it mildly. The Canadian prime minister says his country wants to have a voice when it comes to decisions about what world will emerge from this current global crisis, especially the pandemic and the looming global economic downturn.

Simply put, however, Canada has shown that its vote can be bought by campaign financiers and trade partners, especially the aggressive one next door. That’s the ‘neighbor’ Canada is most concerned about being good to these days, and that just won’t do.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.