Prof. Schlevogt’s Compass № 4: Why in-house work will not be extinct anytime soon – a look at the ‘inverted office power pyramid’

Some pundits say that there are around 1.4 billion prime ministers in India. The reasons for this hyperbolic and satirical characterization are as follows: Apparently, everyone in this former British colony thinks that he is better positioned to lead the country than the actual prime minister, and there seem to be as many different opinions in Bharat as there are citizens.

Likewise, opinions about work-from-home (WFH) differ dramatically (as can be seen, for example, in the wide-ranging comments to my preceding column). In essence, it is a high-involvement topic comparable to high-involvement products such as cars and smartphones, about which consumers care, talk, and argue a lot. Views about the desirability of WFH range from either-or choices to varying degrees of hybridity (combining office and remote work). As regards the latter variant, there are hotly contested arguments about the optimal level of hybridity. Put in a nutshell, you will obtain as many different answers as if you were to ask people in a room what temperature should be chosen on the dial of an air conditioner.

Related to the arguments along the continuum between office work and WFH, armchair experts offer a wide variety of reasons for emerging trends in remote or hybrid work. In particular, this applies to the recent, seemingly unstoppable post-pandemic megatrend of bosses in different countries whipping employees back to the office (see Prof. Schlevogt’s Compass № 3). Yet, in most cases, the reasons given are rather superficial and reductionist, such as a CEO’s alleged narcissism. Clearly, a more sophisticated, comprehensive and dynamic approach is needed to look into the crystal ball as regards the future of work. Such a methodical treatment is especially important to truly understand why the office is there to stay and play a pivotal role (even in a hybrid world of work) at least in the near future.

To evaluate the relative permanency of a phenomenon, you need to understand the fundamental driving forces at play in accordance with the London School of Economics (LSE)’ Virgilian motto “rerum cognoscere causas” (to know the causes of things). This approach is more useful than just presenting descriptive reports or using working from the office as a brand label under the cover of which old cliches are repeated. It also matters for making judgments as to whether a change in an economic pattern constitutes only a temporary fad or an enduring shift.

The following factors, which are partially interrelated, suggest that the office will remain a pivotal gathering place, most likely in conjunction with some remote work, whenever necessary. This verdict undermines fanciful and sweeping Great Reset ambitions, aiming for revolutionary changes to the way we work. Most importantly, we will see that work in the office in many circumstances accomplishes the two most fundamental tasks faced by any organization, that is, coordination and motivation, better than work from home. Thus, the fact that remote arrangements often are not effective is primarily due to fundamental structural reasons, not just the lack of an executive’s competence to manage such novel arrangements.

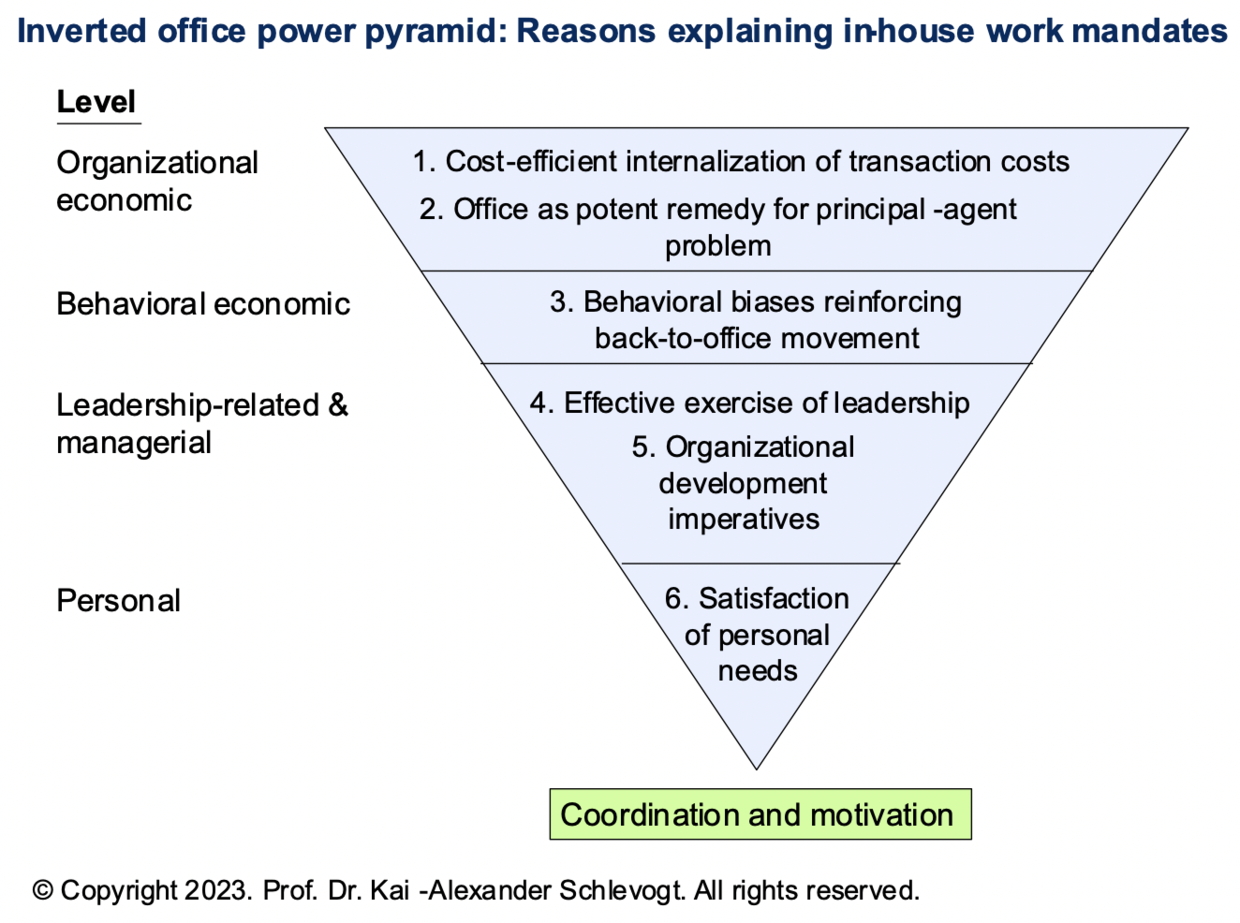

Let us have a look at my detailed “forces at work” analysis of the reasons for the return-to-office megatrend, which are synthesized in my “Inverted office power pyramid” model (see Figure 1). The name is derived from the office’s mighty impact and enduring power to smoothly complete the above mentioned pivotal organizational tasks of coordination and motivation; the pyramid is inverted, since it starts from a macro-level explanatory domain and ends pointedly with factorial micropatterns More specifically, the model covers the following levels: (1) Organizational economic, (2) behavioral economic, (3) leadership-related and managerial, and (4) personal.

Figure 1

1. Cost-efficient internalization of transaction costs

As regards the first reason for the shift back to the office, it is useful to understand one of the key reasons why firms exist at all. The British economist Ronald Coase compared markets with firms as alternative coordination mechanisms. He argued that entrepreneurs will produce a good or service in-house when the transaction costs of doing so are lower than those incurred by procuring it on the market. Examples of transaction costs are the outlays needed for procuring and processing information, as well as the costs of negotiating, writing, monitoring and enforcing contracts. Those transaction costs tend to rise in proportion to increases in complexity and uncertainty, among other things.

In a logical extension, we might argue that work will be performed in a physical office if its associated transaction costs are lower than if the same work were to be

performed remotely. There are strong reasons to believe that, oftentimes, this is currently the case, explaining the corporate urge to call workers back to the office. For example, a complex issue might be easily resolved during an ad hoc office meeting. In comparison, relatively high transaction costs may arise from scheduling a formal virtual meeting of dispersed individuals to solve the given issue.

It is instructive to consider an earlier model of remote work and how it fared over time. In fact, before the Industrial Revolution, work from home was the norm. In the 17th century, the so-called ‘putting-out system’ (also called the ‘domestic system’) was widely used in western Europe. During this proto-industrialization stage, entrepreneurs delivered materials to subcontractors who produced a final good for them - most commonly at home. During the Industrial Revolution, this system, with a few exceptions, became superseded by the factory system, which leveraged significant economies of scales and the power of expensive machines in a centralized location for the purpose of comparatively cost-efficient and high-quality manufacturing. The economic and, as we will see, managerial imperatives for moving production in-house are comparable to office mandates nowadays. Therefore, remote work in the post-industrial era is currently relocated back to the office, which has proven its superior value. In this sense, resorting to widespread work from home would now be a regress, not progress to a brave new world.

2. Office as potent remedy for principal-agent problem

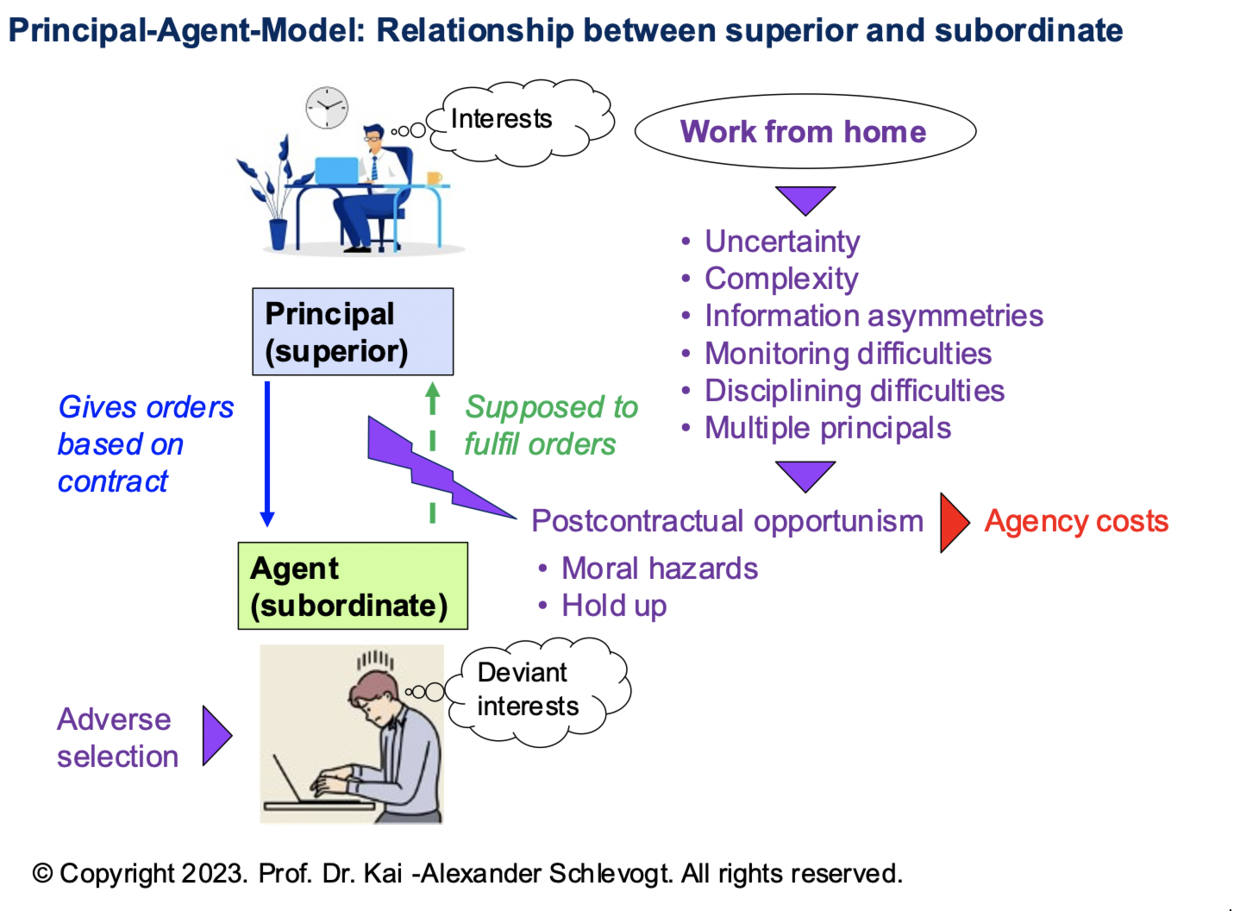

“Principal (P)-Agent (A)-Theory” matters a lot in economics and business. Here is a short primer: According to the P-A model (see Figure 2), a conflict may arise between two self-interested parties in a transaction. In particular, a so-called principal might hire an agent and give him an order, but the agent may have deviant interests and – in an act of postcontractual opportunism – simply not oblige. Postcontractual opportunism includes so-called moral hazards (excessive risk-taking behavior when its costs are assumed by another party) and hold up (one party reneging on a commitment after its bargaining power has increased due to prior commitments by the other party). ‘Adverse selection’ (a process yielding a multitude of ‘lemons’ in used-car markets, for example) might result in a pool of particularly pernicious agents.

Figure 2

Here is an example of the P-A-problem: After ownership and control became separated in publicly held companies, a class of professional managers came into existence, who at times behaved contrary to the owners’ interests. An example would be a manager’s predilection for ‘empire building’, such as the acquisition of a fleet of private jets, which might unduly deflate the profits accruing to the owners.

The potential for postcontractual opportunism and, in turn, ‘agency costs’, which are the tolls arising from the conflict of interest and concomitant opportunistic behavior of the agent, increase, among other things, if there is uncertainty and complexity, information asymmetries exist (such as agents having more information than principals), it is difficult for principals to monitor and discipline agents, and there are multiple principals. The last problem is particularly prevalent and virulent in today’s matrix organizations, where an agent might have to report to two or more bosses. Those might not agree on the objectives for the agent, even though it might be in their best interest to do so – constituting an example of the collective action problem or, in game theory, the prisoner’s dilemma. Given the havoc that ruthless agents can potentially wreak on their principals, much thought is spent on effective ways to reduce such structure-induced conflict. Let us now apply these ideas to office work and telework respectively.

There is strong evidence that agency costs increased due to the WFH spree during the pandemic (with additional problems occurring in the case of widespread digital nomadism). For example, shirking became more popular during the crisis, as seen by the rising popularity of midweek golf or, even worse, midday golf among remote workers (including those higher up in the hierarchy). WFH led to such increases in agency costs due to several reasons: The work environment became more uncertain and complex, it became more difficult for employers to monitor their remote employees, information asymmetries increased concomitantly (despite electronic surveillance systems, which could be used in the office, too) so bosses did not always know what their subordinates were doing during working hours, it became harder for superiors to discipline their remote subordinates, and the multiple-principal problem worsened (since it became more difficult for principals, who were also working remotely, to agree on common objectives for their agent).

Here is an example of problems with monitoring work from home: In a service company operating in an African country, remote workers intent on shirking made the false claim that there were frequent electricity outages in their residential area. This allegedly prevented them from accessing the internet and using their smartphones (which, however, they could have presciently charged!).

In-house work mandates can be explained as a remedy to decrease agency costs. For example, in the office, the task environment might be simpler and more predictable than in a virtual setting. Moreover, it may be easier for a boss to supervise the work of his employees, for example, by looking over their shoulders (thus reducing ‘monitoring costs’ in P-A speak). This is an example of behavioral control, which is more effective than output control when output is difficult to measure, among other things. Better monitoring in turn may reduce the amount of private information and shirking by employees (a form of ‘residual loss’ in P-A speak). Furthermore, the boss may be able to reprimand underperforming subordinates on the spot. Finally, multiple principals could possibly coordinate the objectives to be given to a single subordinate of them more effectively.

It should be noted here that ‘Scientific Management’, developed by Frederick Winslow Taylor, an American mechanical engineer, at the turn of the last century, can be understood as a means employed by managers to correct information asymmetries and thus raise productivity. In 1911, Taylor published his key insights in the book ‘The Principles of Scientific Management’. Time and motion studies of the work performed by employees made it possible to determine how a job may be best performed and how long it would take to do so. Using this method, managers became privy to the exclusive production knowledge of craftsmen, who previously had used their information advantage in the form of trade secrets to extract unjustified high pay. Using their newly gained knowledge about work processes, managers could calibrate differential piece rates, which aligned the interest of principal and agents, in accordance with standardized output targets.

Even nowadays, scientific management and associated cost control systems are still in widespread use, including in service companies such as McDonald’s and UPS. If work is entirely performed at home, though, the power balance shifts back to the employees, who possess private knowledge about their craft, be it physical or intellectual. This applies to both sectors of a dual labor market, that is, the primary, high-value added sector comprised of highly skilled workers and the secondary, low-value added sector comprised of low-skilled workers.

3. Behavioral biases reinforcing back-to-office movement

Insights from behavioral economics are also important to analyze trends in the future of work. Let me again start with a short primer on basic concepts. Biases are unconscious mental shortcuts that enable human beings to reduce the amount of information to be processed and thus make quick, but often wrong decisions. For the purpose of studying the fundamental reasons explaining why the office will remain pivotally important, the so-called proximity bias is important. Put succinctly, this cognitive shortcut prompts a person to develop closer relationships to people who are physically near to him and thus more trusted than to those who are remote. Curiously, this principle was already proposed by Aristotle, who stated that friendship depends on close people meeting each other.

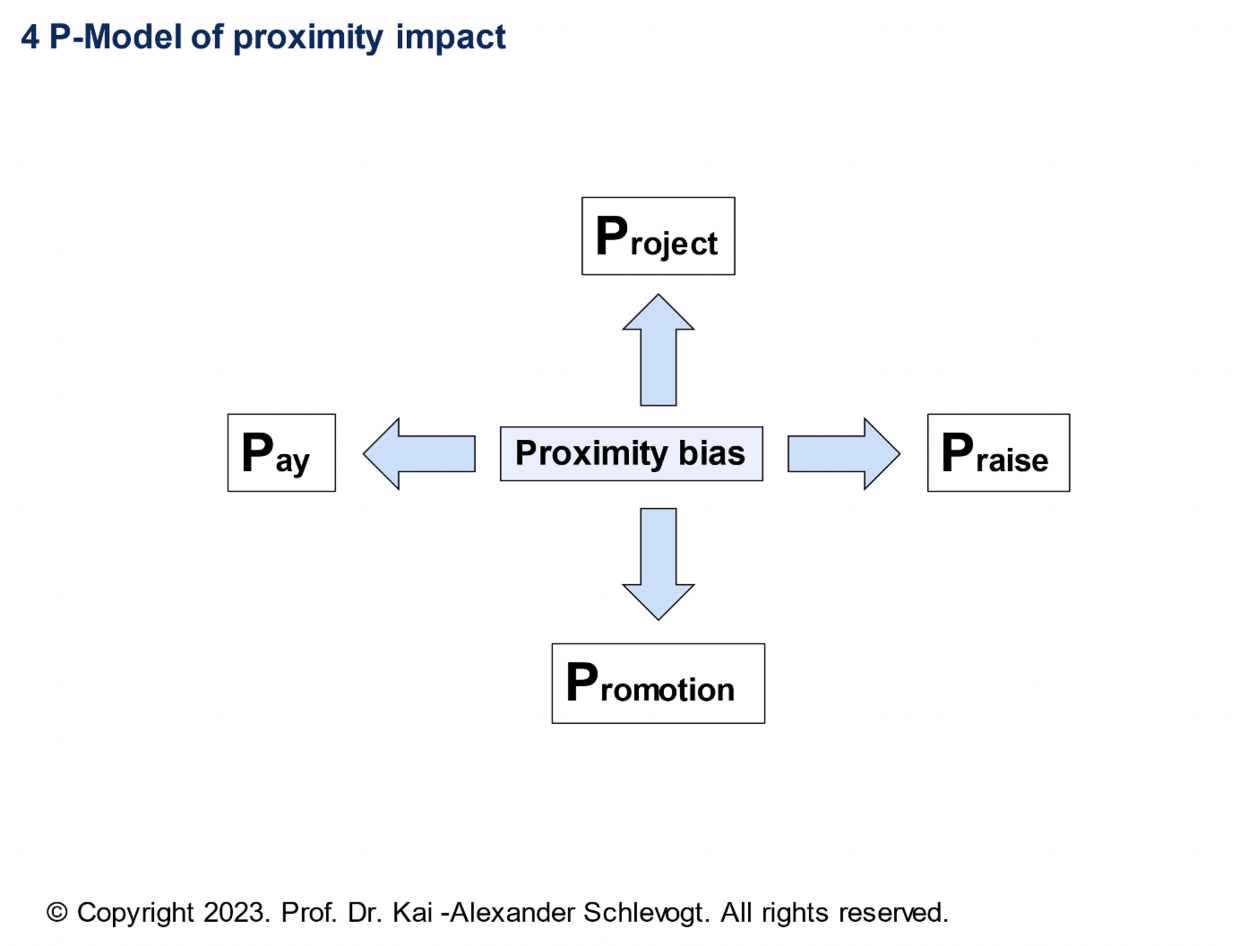

By extension, the proximity bias implies that bosses are likely to develop closer links to office workers than to remote workers – irrespective of the behavior and performance of both groups. This often leads to more favorable treatment of office workers, summarized in my “4-P model of proximity impact” (named after the first letter of each respective result; see Figure 3).

Figure 3

In particular, proximity bias often results in allocating projects to subordinates who enjoyed more face time with their bosses (P1), praising this group of employees (P2), promoting it (P3), and raising its pay (P4). For example, one can easily picture a situation in which a manager seeks feedback on an idea from someone who is physically present rather than a remote worker. He might also be more inclined to discuss the establishment of a new team with those who happen to be in the office and then select its members from this group of office workers. Proximity bias is reinforced by the so-called ‘halo effect’, whereby people with a distinct characteristic – in this case their proximity – leads to preferential treatment. The halo effect can even prompt managers to turn a blind eye to below-average performance of close people. All of this results in a ‘two-class society’, with a superior strata of office workers (constituting the in-group) and remote workers who are second-class citizens (constituting the out-group).

In a larger setting, careers are usually made at the headquarters, not in foreign markets, no matter how large they are. As a consequence, even powerful and highly decorated expatriated ‘mini czars’ from pivotal countries such as Russia and China are usually overlooked after their return, when bosses in the headquarters discuss promotions.

Unequal treatment – paired with superior information by office workers - is likely to unleash a dynamic trend: Ambitious remote workers, who have come to understand the vicinity-induced preferential treatment of their colleagues in the office (perhaps because they have read this column!), are likely to return to the office on their own accord. This trend will be reinforced by another cognitive shortcut, that is, crowd bias. Put simply, this bias prompts people to follow the herd, in this case, the group of remote workers returning to the office.

Besides, managers are more likely to issue sweeping office mandates (possibly even barring remote work altogether and thus creating a non-hybrid work setting) to level the playing field, prevent exclusion and thus systemically and structurally eradicate irrational and accidental favoritism based on propinquity. Across-the-board work mandates for all employees also avoid favoring those with shorter commutes for whom it is easier to work at the office. [To be continued]

Prof. Schlevogt's next column will uncover additional fundamental forces at work driving the seemingly unstoppable return-to-office megatrend.

Note to readers: Please feel free to submit your questions related to a wide variety of political-economic issues in the comment section of this column. Prof. Schlevogt will subsequently endeavor to address these issues in his future columns.