#1917CROWD: Amazing color photos of Russian Empire’s final years & the man who took them

Millions have seen his depictions of the pre-revolutionary Russian Empire, yet precious few remember the name of the chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky. On his #1917CROWD page, the tsarist-era artist opens up to his Twitter followers.

RT’s #1917LIVE social media project, which lets you experience the fateful events of the Russian Revolution in real time, also lets its readers join this historical adventure by creating their own accounts and tweeting under the #1917CROWD hashtag to bring voices of the past to life.

READ MORE: Be part of revolution on Twitter & write your own history with #1917CROWD hashtag

Devoted fans will know Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky by his famous photo-portrait of writer Leo Tolstoy. His revolutionary color tricks and photographs of his time dazzled people in an era of glum black and white photography.

In May 1908 I visited Lev Nikolayevich #Tolstoy in his property Iasnaya Polyana. Here is his portrait and his study #1917LIVE#1917CROWDpic.twitter.com/nVPulWNneT

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 24, 2017

A full-fledged scientist and inventor, he was born into a noble Russian family in 1863 at an estate in central Vladimir Governorate.

He spent a lot of his time giving lectures on his revolutionary photographic method, taking his cue from the three-color principle first developed in the XIX century.

My technique: the images are captured in black/white on glass plate negatives, using red, green and blue filters. 1/2 #1917LIVE#1917CROWDpic.twitter.com/Vq0QuYJ55V

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 18, 2017

He is the first color photographer from Russia. In 1905, at the dawn of more or less usable technologies in this regard, he set about documenting the life and modernization of the Russian Empire with a view to historical education.

Well, and what city is close to Staraya(Old) Ladoga? Of course children, it's Novaya(New) Ladoga! 1909 #1917CROWD#1917LIVE#RussianEmpirepic.twitter.com/6dbhFsIGav

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 16, 2017

Helping Prokudin-Gorsky in his quest is a whole army of European contemporaries, sharing their own approaches to synthesizing color photographs. However, little progress would have been possible without the financial and technological support and promotion he received from Tsar Nicholas II himself.

Happy Holy Friday dear friends and relatives, dear France and Russia, dear America and Prussia #1917CROWD#1917LIVEpic.twitter.com/M6XC3FusPW

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 14, 2017

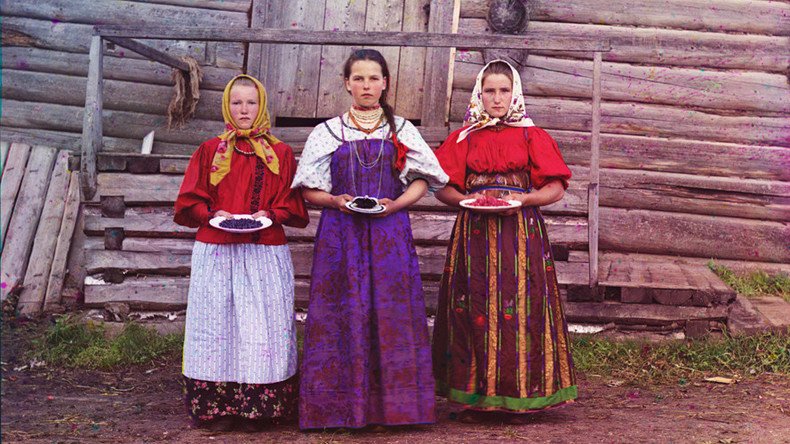

His photographs not only captured the grand capital of St. Petersburg – they also span thousands of miles of the vast empire, documenting its nature, architecture, monuments, bridges and churches as well as the diverse people living there.

Group of children sitting on the hill behind the Church of Saint Paraskevi, Belozersk 1909 #1917LIVE#RussianEmpirepic.twitter.com/YigSoPuOUd

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) May 20, 2017

The method of three-color photography used by Prokudin-Gorsky revolves around taking three photographs in black and white, each through color filters that mimic the basic color spectrum perceived by the human eye – red, green and blue.

Good morning World. Have a wonderful day #1917LIVEpic.twitter.com/NMkFey2F2T

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 26, 2017

The three pictures are then superimposed on top of each other to create a color photograph.

In 1906, brothers Auguste and Louise Lumiere, who were among the first filmmakers in history, introduced him to their revolutionary Autochrome plate technique.

Peasants haying, near Belozersk / Sheksna River at 1909 #1917LIVE#RussianEmpirepic.twitter.com/OLiHisRobt

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) May 22, 2017

But Prokudin-Gorsky was already hard at work on his own technique, a synthesis of existing ones he picked up on his studies in Berlin, Paris and St. Petersburg.

Numerous patents were issued to Prokudin-Gorsky in the 1910s (and will be into the 20s as well) in several countries, including the UK, France and Germany.

Pinkhus Karlinskii 84 years old, 66 years of service. Supervisor of Chernigov floodgate, 1909 #1917LIVE#1917CROWD#RussianEmpirepic.twitter.com/LCCXLsGZFm

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 14, 2017

Helping him document the modernization of the empire was a specially-outfitted railroad car provided by the Tsar. in addition, Prokudin-Gorsky was granted special access to off-limit areas with close cooperation from the bureaucrats of the empire.

This year, I will show you what I love most: the beauty of my country, its peoples and their cultures. My studio in Petrograd⬇#1917LIVEpic.twitter.com/qrrr2V2wfs

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) April 14, 2017

After the Bolshevik takeover in October 1917, he is faced with a tough choice – leave for good, or continue his work under the new government.

Prokudin-Gorsky will eventually leave in 1918 and settle in Paris, where he will die in 1944.

Saint Paul dam in Deviatiny. 1909 #MariinskyCanal#Vytegra River #RussianEmpire#1917LIVE#1917CROWD#Девятиныpic.twitter.com/ibn9tIXrEK

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) May 12, 2017

His rich portfolio will leave behind a treasure trove of 3,500 negatives. Upon his departure, the Bolshevik authorities confiscated some prints they deemed too risky or sensitive. Others were moved to France and later acquired by the US Library of Congress.

A total of 1,902 negatives and 710 prints without the associated negatives remain. To this day, none have ever been found outside of the library.

Fire Squad in the city of #Vytegra , 1909.#RussianEmpire#1917LIVE#1917CROWDpic.twitter.com/eCvYAK9ViC

— Prokudin-Gorsky (@SPGorsky_1917) May 8, 2017