Like mice, humans might soon have their brains controlled externally

Scientists have succeeded in remotely controlling the movements of mice. If human beings are next, how can we deal with the moral and ethical implications of this discovery?

The legendary John Steinbeck took the title of his most famous novella from Robert Burns’s poem "To a Mouse":

“I’m truly sorry Man’s dominion / Has broken Nature’s social union, / And justifies that ill opinion, / Which makes thee startle, / At me, thy poor, earth-born companion, / And fellow-mortal! // The best laid schemes of Mice and Men / Gang aft agley, / And leave us nought but grief and pain, / For promised joy!” (“Agley” is a Scottish word for “awry, wrong.”)

The situation described in these lines is that of a human being apologizing to a mouse for breaking “nature’s social union” due to his thirst for domination over the natural world, which justifies the mouse’s fear of humans and poor opinion of them. The human also concedes that, even if his scheme was well-meant, it turned ugly, causing nothing but grief. But can we imagine the same scene taking place between the human scientist and the mouse on which he performed the following experiment?

New types of human brain cells found in quest for understanding its development & dysfunctions https://t.co/oyf819qRI5pic.twitter.com/E7baUHTU8O

— RT (@RT_com) August 19, 2017

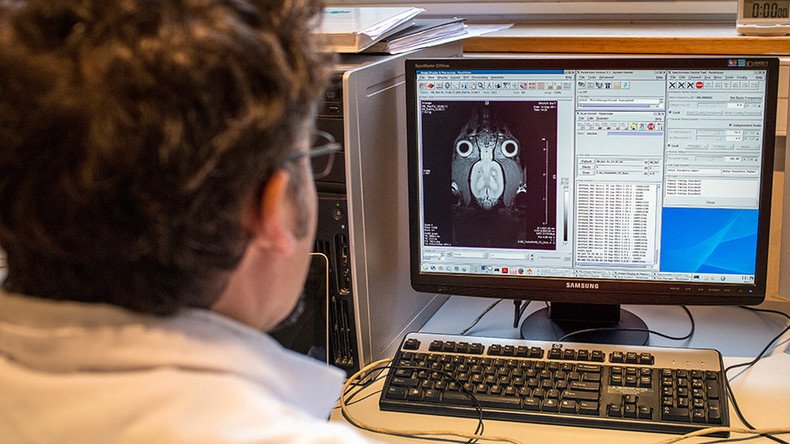

Imagine someone remotely controlling your brain, forcing your body’s central processing organ to send messages to your muscles that you didn’t authorize. It’s an incredibly scary thought, but scientists have managed to accomplish this science fiction nightmare for real, albeit on a small scale, and they were even able to prompt their test subject to run, freeze in place, or even completely lose control over its limbs. Thankfully, the research will be used for good rather than evil, for now at least.

Forced actions

The effort, led by physics professor Arnd Pralle PhD, of the University at America’s Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences, focused on a technique called “magneto-thermal stimulation.” It’s not exactly a simple process — because it requires the implantation of specially built DNA strands and nanoparticles which attach to specific neurons. But once the minimally invasive procedure is over, the brain can be remotely controlled via an alternating magnetic field. When those magnetic inputs are applied, the particles heat up, causing the neurons to fire.

Despite only being tested on mice, the research could have far-reaching implications in the realm of brain research. The holy grail for dreamers like Elon Musk is that we’ll one day be able to tweak our brains to eliminate mood disorders and make us more perfect creatures. This groundbreaking research could very well be an important step towards that future.

This qualified hope: that the research “will be used for good rather than evil, for now” sounds like the well-known doctor’s jokes about “first the good news, then the bad news.”

Because when a new invention like the direct digitalization of our brain is sold to the public, the media, as a rule, begin by pointing out the medical benefits and new opportunities to diminish suffering. Even Stephen Hawking’s little finger – the minimal link between his mind and outside reality, the only part of his paralyzed body that Hawking can move – is no longer needed: with his wired mind, he can DIRECTLY cause his wheelchair to move, as his brain can directly serve as a remote control device. But, as they say, what goes out must come in; and the digitalization of our brain opens up unheard-of possibilities of control.

‘Living dead’: Billions of people simply not needed in emerging global economy (Op-Ed by Slavoj Žižek) https://t.co/1tHx1PPznN

— RT (@RT_com) September 18, 2017

Not so new

Incidentally, the news we speak of is not exactly fresh: already in May 2002, it was reported that scientists at New York University had attached a computer chip able to receive signals directly to a rat's brain, so that one can control the rat (determining the direction in which it will run) by means of a steering mechanism (in the same way one runs a remote-controlled toy car). For the first time the will of a living animal, and its spontaneous decisions about the movements it will make, were taken over by an external machine.

Of course, the big philosophical question here is: how did the unfortunate rat experience movements which were effectively decided from outside? Did it continue to experience it as something spontaneous (i.e., was it totally unaware that its movements are steered?), or was it aware that something was wrong and that another external power was directing its movements?

Even more crucial is to apply the same reasoning to an identical experiment performed with humans (which, ethical questions notwithstanding, shouldn’t be much more complicated, technically speaking, than the case of the rat).

When it comes to the rat, one can argue that we should not apply to it the human category of experience, while, in the case of a human being, we need to ask this question. So, again - will a steered human continue to experience his movements as something spontaneous? Will he remain totally unaware that his movements are steered, or will he become aware that something is wrong and an external power is deciding his movements?

And, how, precisely, will this external power appear: as something inside the person, like an unstoppable inner drive, or as simple external coercion? If the subject will remain totally unaware that their spontaneous behavior is steered from outside, can we really go on pretending that this has no consequences for our notion of free will?

Intelligence linked to 52 ‘smart genes’, scientists discover https://t.co/mdm26QVKLspic.twitter.com/n7QgoIYVKw

— RT (@RT_com) May 28, 2017

Real world example

With a little bit of irony, one can claim that we already have a case of such a steered human being in our political reality. For instance, when Greece’s Alexis Tsipras, a partisan of anti-austerity politics, after triumphantly winning a referendum saying NO to EU financial pressure, all of a sudden changed his position and agreed to enact the toughest austerity policies. Was it not as if the financial and political powers in Brussels pressed a button and make him act like their remote-controlled toy? Many observers noted that, after this change, when Tsipras appears on TV screens in the company of big European leaders, there is something strange in his behavior: he often just stands and smiles, as if he is not fully aware of his acts.

While this is little more than a political joke, perhaps in rather bad taste, of course big questions do explode here, not only basic philosophical ones but also political ones. When Musk says “we’ll one day be able to (do this or that)” – WHO will this “we” be? Corporations, governments, or anyone with money?

However, one thing is clear: science and philosophy will have to combine their forces. It happens from time to time that a similar idea appears in two different fields of theory which do not intercommunicate at all – say, in “postmodern” speculation and in empirical science. This is what has happened in the last decades with the idea of theoretical anti-humanism or of an inhuman subject which played an important role in contemporary French thought, from Foucault and Lacan to Badiou.

How are naked mole rats able to last 18 minutes without oxygen? https://t.co/hCcprD8Owspic.twitter.com/NwDsSReq1T

— RT America (@RT_America) April 21, 2017

Lately, the cognitive sciences have proposed their own version of anti-humanism: with the digitalization of our lives and the prospect of a direct link between our brain and digital machinery, we are entering a new posthuman era where our basic self-understanding as free and responsible human agents will be affected. In this way, posthumanism is no longer an eccentric theoretical proposal but a matter of our daily lives.

Can these two aspects be brought together into a unique theoretical perspective, or are they condemned to speak different languages (“postmodern” theory reproaching cognitivism as a naïve naturalist determinism, and cognitivists dismissing “postmodern” theory as an irrelevant speculation which remains rooted in the traditional philosophical space)? Perhaps only such a dialogue can save us.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.