Prestige does not necessarily mean progress: A history of the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize has stirred controversy for decades. Who decides on the winners of this prestigious award, and does their choice reflect courage or conformity?

It’s Nobel season again – that time of year when Scandinavian dignitaries gather to announce the winners of some of the world’s most sought-after prizes in chemistry, physics, medicine, literature and, of course, peace. While the natural science awards are typically greeted with a vague accolade from the media and public, which, Morgan Freeman’s efforts on Through the Wormhole, notwithstanding, remains blissfully ignorant on the subject, the prizes for literature and especially peace can become the subject of controversy.

Is the Nobel Peace Prize really fair? Does it reflect who has contributed most to their respective field or are the awards merely an excuse to invoke a cause célèbre and drown out more important matters?

To truly understand how and why the Nobel Peace Prize is given out, it’s necessary to know a thing or two about the institution’s founding principles.

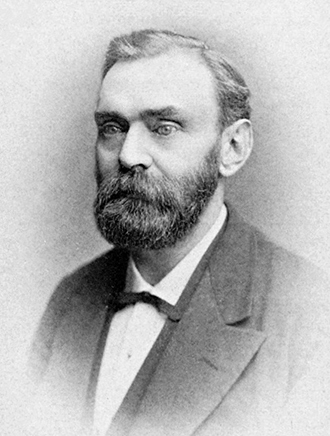

The life and times of Alfred Nobel

Alfred Nobel, the eponymous founder of these enviable prizes, is best known for inventing dynamite, an explosive with primarily industrial applications. His day job as an armament tycoon who invented and refined other explosives more suited to warfare is less well-publicized today, as is his heavy involvement in his brothers’ Caspian Sea oil business. However, during his own lifetime, Alfred Nobel was a very wealthy and even somewhat controversial figure. When his brother Ludvig died, one newspaper, under the mistaken impression that Alfred was the Nobel brother who had died, penned an obituary for him (eight years too early, as it later transpired), naming Alfred “the Merchant of Death,” before passing the less-than-flattering comment that he had made his fortune out of finding ways to kill more people faster.

It is widely believed that this serendipitous mistake served as Alfred Nobel’s wake-up call to consider his ultimate legacy. In this version of events, Nobel would be cast in the role of a Victorian Iron Man, determined that the evil he had brought the world be balanced by good, with a side option of someday being portrayed in celluloid by Robert Downey Jr. It is believed that to this end, he bequeathed the majority of his substantial fortune to found the Nobel Prizes, much to the surprise of all who knew him.

Nobel, however, was no radical. At the time of his death in 1896, democracy, as we know it, had not been established in Europe and Nobel was not an advocate of efforts to do so. Not for him the idea of mass rule or the common man participating in affairs of State. The Nobel Prizes were to hold with propriety and be an elite, invitation-only affair. Over a hundred years later, this elitism is still reflected in the prize selection process, including the selection process for the Peace Prize.

The Peace Prize Selection Process

Given the propensity of media to celebrate the Nobel Peace Prize as a contribution to humanity, it might come as a surprise to learn that only certain “qualified” individuals are permitted to submit nominations, namely:

- Members of national assemblies and governments of states

- Members of international courts

- University rectors; professors of social sciences, history, philosophy, law and theology; directors of peace research institutes and foreign policy institutes

- Persons who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

- Board members of organizations that have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

- Active and former members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee

- Former advisers to the Norwegian Nobel Committee

Since no one in this elite nominating circle has any personal interest in rocking a system that they have done very well out of, it is quite heartening that divisive figures like American whistleblowers Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning ever make it onto the nomination list.

However, once through the nomination process, one’s chances of winning are greatly improved if their cause is the type more conducive to establishment interests or better yet represent the type of cause that no one is willing to argue about. Political correctness rather than revolutionary gusto is the asset to hold here. This is because the final decision on the winner lies in the hands of a five-member Committee appointed by the Norwegian Parliament. Committee members are usually former politicians who are chosen to reflect the parliamentary composition.

Current members are:

-Thorbjorn Jagland, briefly Prime Minister of Norway in the 1990s and Secretary-General of the Council of Europe since 2009

- Kaci Kullman Five (a former Conservative MP and Minister for Trade)

- Inge-Marie Ytterhorn – former MP for the Progress Party

- Berit Reiss-Anderson – former Labor Party member and head of the Norwegian Bar Association

- Gunnar Johann Stalsett – former Chairman of the Centre Party

Not only is this a crowd unlikely to be caught swinging from the chandeliers and shouting “let freedom reign” it is hard to imagine the internecine warfare of national party politics allowing them to agree on much besides the fact that child exploitation is not quite all right.

In fact, incessant politicking, and the narrow selection process, has led to a surprising number of people failing to procure the prize (in its 114 year history it has only been awarded 95 times) which must be granted during the nominee’s lifetime. While the selection committee did manage to hand out the award to Martin Luther King Jr. (1964), Polish Solidarity activist Lech Walesa (1983), apartheid-opponent Desmond Tutu (1984) and Mother Teresa (1979), Mahatma Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, Nigerian environmentalist Ken Saro-Wiwa, and Czech dissident Vaclav Havel all missed out, having at one time or another stepped on the wrong toes, while Nelson Mandela was only attributed the award jointly with F.W. de Klerk (a long-time white South African politician) in 1993, arguably well past the period when he could have used the legitimacy conveyed by the award the most. Considering the Prize’s checkered record and politically-fraught selection process, the youth of one of this year’s winners (Pakistani child education activist Malala Yousafzai) may have been more of a help than a hindrance – at 17 she hasn’t had much time to give opponents a handle against her and that is often a vital precondition of going home with the hardware.

The Purpose of the Nobel Peace Prize

The purpose of the prize, however, must also be considered. It’s not, contrary to public opinion, simply an award for saintliness. According to Nobel’s will, the prize was to go: "to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

So little has been done to abolish or reduce standing armies that the committee tends to focus on the other two criteria, often in a surprisingly directive manner. This year, they pointed out that the award would be shared by a Muslim Pakistani (Malala) and a Hindu Indian Kailash Satyarthi who work to end economic exploitation of children. The message would seem to be that, at the very least; some fraternization between nations is going occur on the podium. As civilians without direct political power, Kailash and Malala will likely find this an easier task than some previous winners have. Indeed, some of the Committee’s most controversial decisions have been engendered by their apparent desire to not so much reward peace-making as to dabble in it themselves. To hand out the award, in other words and hope that reality will follow suit.

Perhaps the most controversial instance of the Committee’s desire to play politics was the 1973 joint award of the Peace Prize to Henry Kissinger, the then US National Security Advisor, and Le Duc Tho, a leading figure in the North Vietnamese forces for negotiating a ceasefire. Le Duc Tho declined the prize on the grounds that the ceasefire hadn’t been implemented, becoming only the second person in history to do so. Henry Kissinger had no such compunctions, either about accepting the prize, which he did “with humility,” or about continuing to prosecute the Vietnam War for another two years post-acceptance, while the medal presumably gathered dust on his shelf.

A similar kerfuffle erupted when the award was given to Yassar Arafat, Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin in 1994 for negotiating the Oslo Accords between the parties of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Rabin, Israel’s Prime Minister at the time would be shot dead by a right-wing Israeli mere months after receiving the prize and twenty years on, we seem further from peace in the region than ever. As the closing chapter in this controversial trilogy, Barack Obama carried home a peace prize in 2009, just one year into his first term as US President. The Committee had apparently hoped that renditions, unauthorized wars, drone strikes and Guantanamo Bay would soon be relegated to history. Five years later, the best that can be said is that it’s rather fortunate PR that Malala was injured by the Taliban and not by a drone strike ordered by her predecessor and fellow Laureate. It could have made for some awkward on-stage moments.

As these examples indicate, there is a certain tendency for the Nobel Peace Prize to go not to people who have achieved anything particular, but who might be susceptible to the public pressure of trying to live up the prize once awarded. Thus, it is not so much about picking the best or the greatest or, indeed, the only worthy recipient. With only one yearly prize to hand out, tactics play a big role and this is complicated by the considerable rewards at stake.

The Money

It’s arguable that much of the prestige of a Nobel Prize is generated by the fact that it is backed up in hard cash: approximately $1 million worth. It would be hard to imagine nominators and committee members failing to consider where that money could be spent most effectively. It might help nominees to fall into a sweet-spot where they champion a cause which exists, but whose scope is relatively limited. Seen this way, guaranteeing childhood education might be a more feasible target than ending State surveillance. Fiscal considerations may also explain why the reward so often goes to United Nations agencies and international NGOs – usually about once every five years. While many of these organizations arguably do not contribute to world peace in the manner that Nobel envisioned over a hundred years ago, they often suffer from budgetary deficits and $1 million can certainly plug some holes. As the stewards of Nobel’s vast fortune, decision-makers tend to go for the safe option on where his money should be spent, rather than gambling on new or untested ideas.

Conclusions

The science prizes may be given out for progress (or so we, in our ignorance, assume), but it helps to think of the Nobel Peace Prize as more of a statement piece: the product of a long consultation process between the global gentry and the guardians of an armaments tycoon’s fortune. As such, it is no surprise that, if anything, the Peace Prize values tend to lag behind the global progress most citizens would like to see by a good decade if not more. It’s not that people tend to disagree with the choice of recipients, more that while there are undeniably some hold-outs (most prominently in regards to this year’s awards, the guy who shot Malala in the head), they tend to represent a point upon which broad consensus was reached several fashion cycles back.

Some people might be disappointed at the Committee’s various choices, hoping for a more progressive, militant or radical stance from this agenda-setting institution, but, as Austin Powers would have said, that’s not their bag, baby. Just because something is the most prestigious doesn’t mean it is the most progressive. Quite the opposite.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.