‘Too late for UK to stop Romanians and Bulgarians immigration influx’

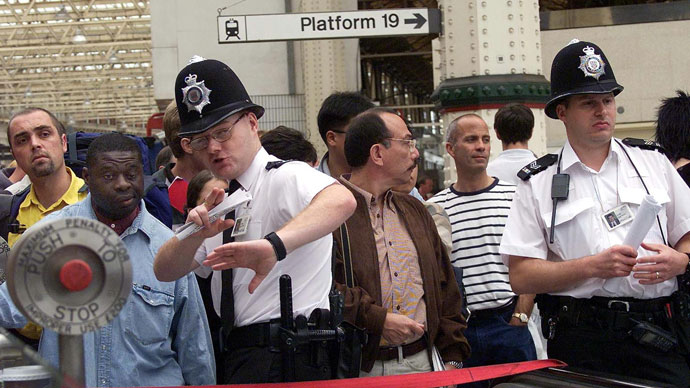

Following the Woolwich murder, the UK again saw a sharp rise in anti-Muslim sentiment. Though London has long grown into a majority minority city, Britain has yet to become a successful multicultural society, analyst David Goodhart told RT.

The multicultural and multi-faith London was shaken to its core

when 25-year-old Lee Rigby was brutally killed and beheaded in

late May in broad daylight by two people shouting "Allahu Akbar!"

The incident saw anti-Muslim sentiments grow in the British capital, with the English Defence League (EDL) laying the blame for the Woolwich murder on Islam and staging a protest in London.

Another European capital has also seen a recent rise in ethnic

tensions, with clashes in Stockholm raging for days between

police and themostly immigrant population.

These recent developments echo statements by top EU politicians like Angela Merkel and David Cameron on how multiculturalist policies have failed, though no alternative has been offered so far.

The next immigration challenge the British face is dealing with Romanian and Bulgarian immigrants, who can easily migrate to the country next year after restrictions are lifted on these two EU members, who joined the union in 2007.

RT spoke with David Goodhart, the director of the nonpartisan think tank Demos and the author of 'The British Dream,' which looks at postwar multiculturalism, national identity and immigration in the UK

RT:In the book you make the case that liberal immigration is undermining the bonds that hold Britain together. Can you elaborate on that for us? How so? Why did you write a book on that?

David Goodhart: Well, it is trying to look at the historical, economic, social arguments around immigration. And so it’s a huge, controversial, fascinating subject. I’m looking at the postwar period and how it’s affected the British society. I try to look at it as objectively as possible and look at the success stories and the failures. Not only from the point of view of people coming here, but also from the people who are already here. And we tend not to look at immigration from the point of view of how it’s affecting the already-existing communities in Britain.

RT:As you say yourself, this is a very controversial topic. Why do you think this is such a divisive issue, particularly in Britain?

DH: I don’t think it is any more divisive than it is in any other place. I mean the people overwhelmingly are not in favor of large-scale immigration. Throughout history that has been true and that remains true even in our societies today, which are on the whole much more liberal, much more tolerant with much less racial discrimination. People still have a bias in favor of the familiar. It always has been and it always will be. So, it’s not particularly controversial here at the moment I think. It has become politically very sensitive here. The outcome of the next general election in Britain in 2015 could well hang on the number of people who come here when our labor market is fully opened to them from Romania and Bulgaria at the beginning of the next year.

RT:Which political parties if any do you think are actually on point with this issue right now?

DH: One of the big stories of British politics in the last generation is the gap, the difference between left and right has narrowed, but the gap between the whole of the political class and the voter has widened. And immigration is sort of emblem of that widening. It applies to other areas too, like welfare, Europe. And these are issues that Labour in particular is very sensitive on, rather exposed on. But the instinct and intuition of the MPs is often a mile away from the ordinary voter. If anything, Conservatives tend to be closer to the ordinary voter on these issues.

RT:You titled your book ‘The British Dream.’ What exactly do you mean by that? What is the British dream?

DH: This is obviously borrowed from the idea of the American dream. The idea that if you want to be a successful, an open multiracial society, you need to tell yourself stories of that. You need to tell yourself stories about good immigration, about successful minority people, who are contributing to Britain, not damaging the interests of the people who are already here. And we do have those stories, we indeed have more of them than America, which is full of extremes and remains a very racially divided and organized, and very violent society.

And I don’t think we want to go down that road. So, the paradox is we need to borrow some of the American language and the easy talk about patriotism. American nationalism manages to include almost all people that go to America. We need to borrow some of that language in order to avoid American outcomes.

RT:You particularly seem to pinpoint that, in your

opinion, integrating poorer nationalities into richer society

doesn’t necessarily ensure a richer life. Critics would say that

that overlooks the fact that integration obviously provides

greater security. And this is sort of a backbone of our welfare

state. What would you say to them?

DH: Of course, if people are coming from poorer countries,

they usually become richer and more secure. But nobody can

reasonably start from the point of view of the world as a whole.

Well, some people do. There are lots of people in the academic

world, some people on the cosmopolitan left of politics, people

who I call the 'global village-ists.' We are not a global

village. We as human beings are generally more particularists.

Our allegiances sort of flow out from family and friends to

towns, to nations, to the whole world, not the other way around.

And it doesn’t make sense if you believe in the nation-state,

which I do.

I think without nation-states the world would be a ghastly place,

it would be like ‘1984.’ Democracy requires relatively

small manageable units of people, in which people speak the same

language and understand each other. The world would really be a

terrible place without nation-states I think. Nation-states

remain the foundation of most of most of the political goods in

the world. But if you can have nation-states, you have to put the

interests of fellow citizens first, otherwise what’s the point in

being a national citizen? If you find your rights are overridden

by the rights of somebody with whom you feel no allegiance from a

distant part of the world?

RT:What are your thoughts on the labor market being opened up to Romanians and Bulgarians?

DH: It’s hard to stop it now. We are still part of the

European Union. This was written in the rules way back in 1957,

it’s part of the treaty of Rome, it’s free movement. I think it’s

being wrongly interpreted in the sense that was never intended in

1957 that the European Union should be an economic space which

included countries and groups of countries with average standards

of living one-fifth or one-quarter of rich countries like

Britain. And free movement in that context is completely

different to free movement as it is in practice happened between

1957 and the early 2000s. Hardly anybody lived permanently in

another European state. I think it was not 0.1 percent of the

population who in 2000 lived permanently in another EU state.

RT:Do you see that as part of the problem, that as we

are dealing with the immigration issue here in Britain, we are

also having to balance with our commitment to the EU?

DH: The big negative shock particularly for the poor

people in Britain came with the opening for East Europeans –

Romania and Bulgaria issues are a continuation of that, a sort of

late phase of the 2004 opening. So, it’s too late to stop it. You

can try to demagnetize the country as much as possible. And

Britain is a very attractive place to come for a number of

reasons. Partly it is because of the English language, partly

because we are a pretty tolerant country where there are lots of

minority groups already.

There are already 200,000 people here from Romania and Bulgaria who’ve come under various temporary work schemes. How do you prevent the big increase is sort of technical question. We simply won’t know. I think actually not that many people will come. Like in 2004, all of the other countries are opening up at the same time. Many Romanians and Bulgarians have closer connections to other richer EU states. It’s been sort of ugly, all of this moaning about Romanians and Bulgarians, when actually all of the hostile publicity may have put people off coming.

RT:What would you want people to wake up to when it

comes to immigration?

DH: London is a great multicultural city. But London has

experienced a huge amount of so-called 'white flight.'

Lower-income people mainly in the outer suburbs leaving London

because they think it’s changed too fast for them. And that does

include the change in ethnic composition of the place where they

live. And I think you can’t say London is a successful city, as

between 2001 and 2011, 620,000 white British people left the

capital, which is why now London is a majority minority city.

Quite unexpected.

None of the academics picked that up because they weren’t

watching the outflow. It’s easy enough to track the inflow. But

they don’t live in the suburbs, where this was happening. And I

think we do have to worry about that, if we want a balanced

society. On integration people have conflicting intuitions. On

the whole people want to live among people roughly like them.

That can evolve over time and become broader. But we also think

that a healthy society is one where there is a lot of

communication and contact across ethnic and social boundaries.

And we are not seeing enough of that in Britain. And we do have,

I think an integration problem.

RT:Do you think that can be just an issue of time and

patience?

DH: It is partly. And you can see that already with the more successful groups in the suburbs of northwest London, where there are lots of British Hindu Indians professionals living in the same suburbs as their white counterparts. But then there are certain groups that are less successful and are not integrating so fast. They may be just a generation or two behind. And that’s the optimistic story and may be true. But even for them I think it wouldn’t harm to speed it up with integration.

RT:When it comes to how Britain is handling the issue

of immigration in particular, how do you view our relationship

with the EU, as contributing or not to that?

DH: Part of the point of the Euro was to disperse German

power and to prevent the rise of nationalism in Europe, and it’s

done precisely the opposite on both fronts. We now have serious

national resentments particularly in countries like Greece that

have had policies imposed on them by Brussels and Berlin. And the

way that the Euro has developed is also giving all power in

Europe essentially to the German Chancellor. And David Cameron in

his speech a couple of months ago on Europe declared there would

be a referendum a couple of years after the next election. He’s

further reinforced that.

And he has handed Britain’s destiny in Europe to Angela Merkel by saying we are going to renegotiate terms of Britain’s membership in EU, after which I will present these new terms to the British electorate and I hope that they will approve them and we will stay in the European Union, but who will decide whether we get what we want and anything that’s presentable as some kind of victory to the electorate, it must be Angela Merkel or whoever the German Chancellor in 2017.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.