In Washington, money trumps votes: Is the US still a democracy?

The United States for years has touted itself as the “world’s oldest democracy,” but it doesn’t seem to be as democratic as it might appear.

It’s a claim based mainly upon a document – the US Constitution – that back in 1788 established a system of three branches of government; executive, legislative and judicial. The first two of which were to be elected and the third, appointed and approved for life by those who the people had elected.

On paper it sounded good, but even from the outset the US was never really a true democracy, which means “government by the people.” Women only got the right to vote in 1920 and black people were widely blocked from voting in the South until the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The US as a democracy might seem credible, but a pair of political scientists, analyzing two decades’ worth of polling and looking at legislation passed by Congress, claim it is not as democratic a country as it might appear, this time for a new reason.

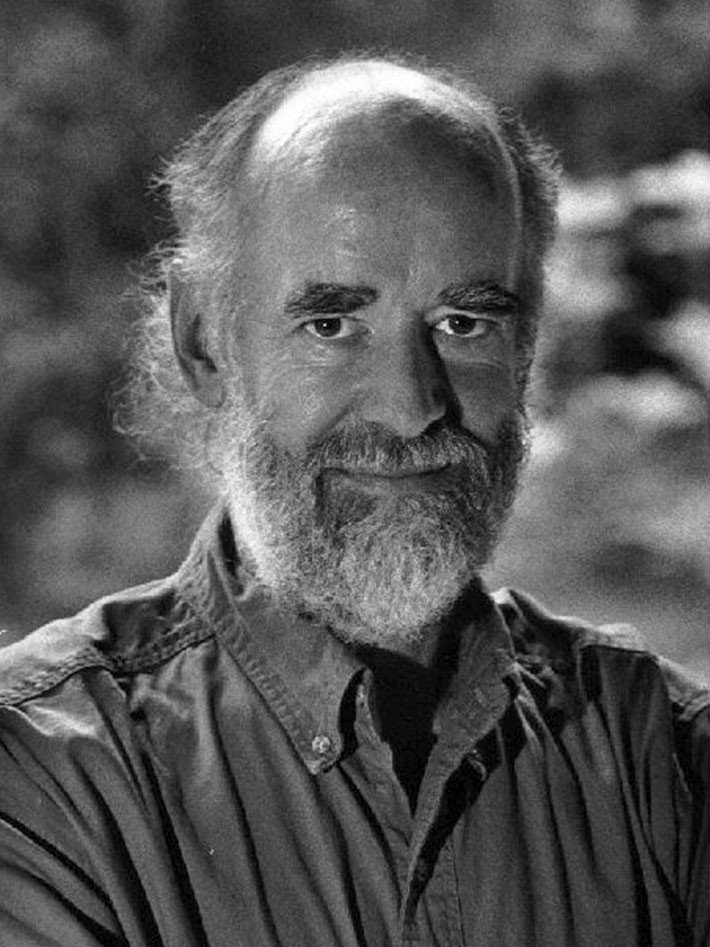

Prof. Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University in their recent book Democracy in America?, have found that only two percent of the legislation passed by Congress since 2006 has been in line with the wishes expressed by the vast majority of US citizens. The rest, they say, has been legislation supporting policies and actions advocated not by the people but by corporations and the richest 10 percent of the population.

Examples:

* By wide margins, Americans have supported the idea of expanding Medicare, the socialist-style of government-operated health insurance system that is currently available only to the elderly and permanently disabled, and the idea of increasing Social Security benefits paid out to retirees and the permanently disabled. Instead of that happening, Congress planned to chip away at most retirees’ benefits and raise the individual’s cost of obtaining Medicare coverage.

* By wide margins, Americans favor making the federal tax system much more “progressive” with significantly higher taxes on the rich and on corporations, but Congress has instead repeatedly offered tax cuts to corporations and lowered the tax on the wealthy, and has raised taxes for much of the middle class.

* Most Americans want strict regulation of the large banks that caused the 2008 financial crisis and a resulting major recession, but Congress over the past few years has been reversing stricter bank regulations that were put in place during the Obama administration.

In their book Gilens and Page write: “The preferences of the average American appear to have only a miniscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.”

Gilens and Page attribute what they call a dramatic decrease in popular influence over government policy in the US to the increased role of money in American politics. This has been due to both a legislative weakening of laws banning large and even direct corporate donations to presidential and congressional campaigns, and to court decisions overturning laws that sought to outlaw or restrict such legalized bribes. As well they point to a widening gap between the wealth of average Americans and the truly wealthy – both a cause and an effect of the weakening of democracy at the national level.

It wasn’t always quite that bad, suggests Prof. Page in an interview with this reporter. Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, politicians in Washington still had to react to popular public pressure. In the early 1960s, for instance, a massive movement developed among black Americans and their white supporters calling for civil rights, like the unfettered right to vote and an end to segregated schools, public restrooms and restaurants.

This movement was accompanied by huge uprisings in most major US cities by frustrated black residents. In response Congress passed landmark civil rights and voting rights legislation. Federal authorities also aggressively challenged segregation. A few years later, in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, an equally massive movement against conscription and the US war on Vietnam helped bring that unpopular war to an end, marking the first defeat of the US military in its history.

Page, in a comment for RT, said, “I would argue that antiwar protesters did in fact hasten the end of the war,” suggesting the protests like those against the Vietnam War or demanding civil rights, can counter money politics by both “raising the costs for policy makers” and by succeeding in “demonizing opponents” and “building a large coalition based on shared values.”

He adds that the current situation, with money appearing to control Washington politics, could be changing for the better. Pointing to the recent Congressional elections in November, which saw a number of conservative Republican and even Democratic members of Congress lose their seats to often younger and more radical opponents.

“The nascent democracy reform movement has real potential” to shake things up in Washington, he says.

The results of that election, which led to a shift in control of the House of Representatives from Republicans to Democrats, but more importantly, to a greater role for more radical newly elected Democrats, are forcing “establishment Democrats” to “move to deal with” the radicals’ agendas and “preempt challenges to their power,” Page suggests.

If Page is right, and if a popular movement to challenge the influence of big money on politics grows, with calls for candidates to refuse large campaign contributions and corporate support, the influence of money on politics in Washington could start to be seriously challenged in the coming years.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.