Brawler, drinker, womanizer, hero? Trying to piece together the truth of Yuri Gagarin

On the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s death, instead of trying to delve into the unknowable minutia of his final flight, an attempt to understand what really made the first man in space tick down here on Earth.

Gagarin died at 34, before he had a chance to live through the Moon landing, Perestroika or the fall of the Soviet Union, and before he could tell his own story. Almost everything that is known about him is second-hand information colored by personal and official biases. Much remains unavailable in archives.

But that makes the man who was undoubtedly once the world’s biggest celebrity only more fascinating.

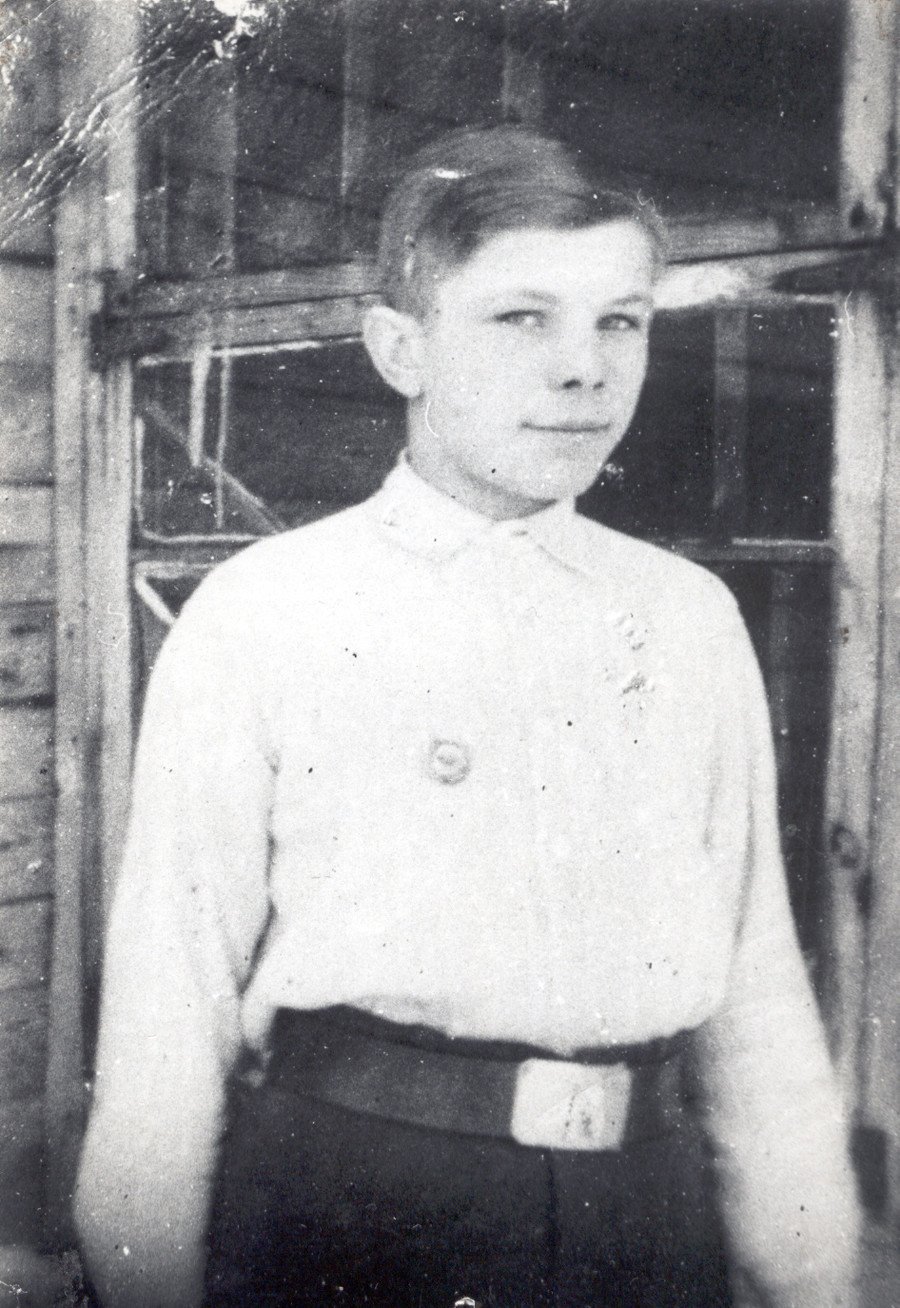

1. Accounts of Gagarin’s childhood under Nazi occupation, although authored by his relatives, read like the Gnostic gospels of an infant Jesus, with Yuri chosenness already signposted by acts of prepubescent heroism. It may be true that he helped rescue one sibling hung up onto a tree “like a Christmas decoration” and another used by Germans for “target practice,” all while trying to sabotage the life of a stereotypically cruel German who quartered himself in the family home ‒ or it could be a family lore elevated to Soviet propaganda myth-making.

2. In the first three-dimensional account, published by a classmate, the tween Gagarin gets drunk on spirit from an unattended cistern, peeps on a sunbathing girl from his class, and goes on moonlit dates with another. Described as unusually mature for his age, he is a born leader and a moral rebel, always ready to fend off other gangs with fists and still-plentiful weapons in an atmosphere of simmering post-war violence.

3. In recollections from his school, metallurgical training college, and later pilot academy Gagarin is most reminiscent of Max Fischer from Rushmore – the boy who joins every club, and seizes every single opportunity, however unsuitable. Despite being 5”2 he is the captain of the basketball team, he plays trumpet in a band, he takes photographs… That last hobby doubles as an icebreaker with attractive girls, most of whom like his courage in taking the first step (though a few find him overbearing… and too short). He is a “bouncing ball” ready to overcome every obstacle, often catching up with more privileged youths through quickness, willpower and ambition. This matches up well with accounts of Gagarin throughout his life.

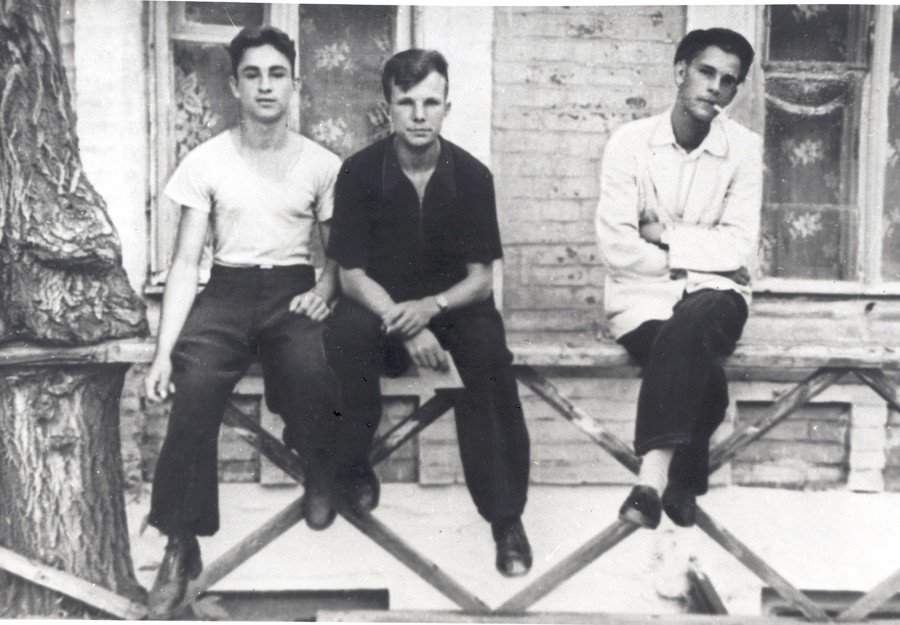

4. Not everyone is taken in by the boy scout enthusiasm that makes Yuri a teacher’s pet. From the age of fifteen, when he travels to Moscow, he spends most of the next decade living in dorms, sometimes 30 men to a room. In his Orenburg pilot school he is appointed the leader of his cadet squad and is put in charge of the waking times, morning exercise and other disciplinary routines of his fellow students. He is a stickler to the rules (and possibly a snitch) and three others warn him to go easy. He doesn’t listen and this is one brawl he doesn’t win: in the middle of the night three students wrap themselves in towels and batter Gagarin, who spends weeks in hospital afterwards. The three men are expelled and given jail sentences for the assault.

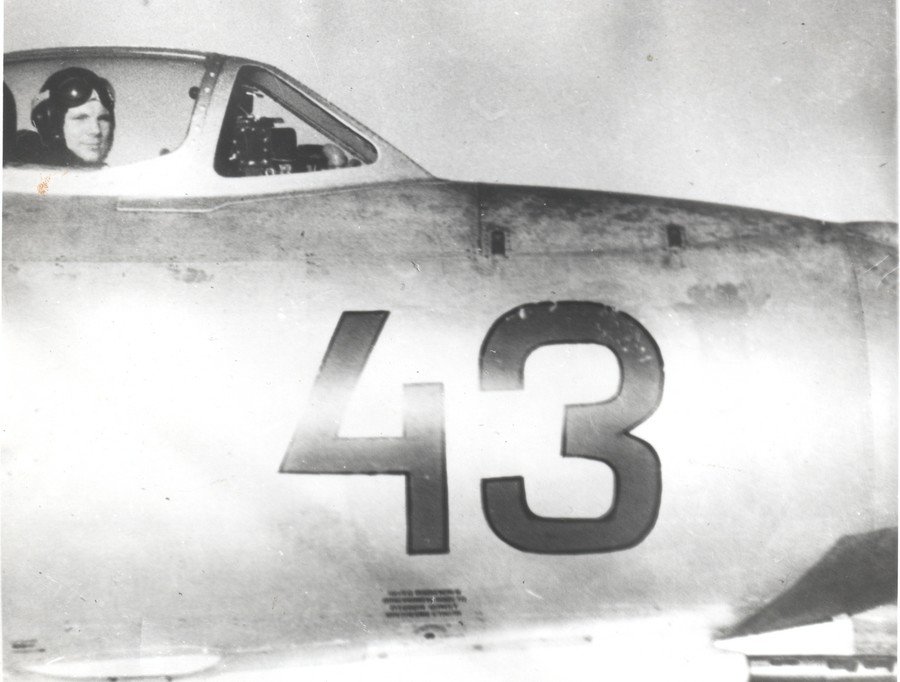

5. He initially struggles to land his MiG-15 and stands on the verge of expulsion, but he is allowed to prove himself after taking off in a flight he wasn’t even sanctioned for. He graduates and is stationed in Lapland. In fact, as would perhaps be expected of someone who traveled through his life journey, Gagarin receives several similar lucky breaks ‒ up to a point. The MiG-15 is also the plane in which he will die.

6. Gagarin is not just funny, he is “always on.” Some of the other 19 trainee cosmonauts find the incessant stream of retorts, stories and pranks exhausting and irritating, but it serves Gagarin in good stead during the scientifically sadistic training. He sings romantic hits to observers on the one-way radio while moored for days in an isolation chamber. Gagarin can also be disarmingly honest. When doctors give a toxic agent to the cadets to test their reaction, he is the first one brave enough to admit he is unwell, and in the final selection interview, he confesses when he doesn’t know the answer to questions. Even when he tries to be ingratiating by staying behind to ask for personal guidance from his superiors, his ploy is so transparent and lacking in malice that he comes across as guileless.

7. But Gagarin does lie – about the emergency in which his re-entry module fails to promptly separate from the service block, causing the cosmonaut to spin frantically at huge g-forces, thinking he might die, though the modules come apart and the trajectory stabilizes. Gagarin offers to include the incident in his flight report, but Soviet space tsar Sergey Korolev asks him not to “for the good of the program,” reassuring the cosmonaut that the malfunction will be studied internally. Gagarin also goes along with the fiction that he landed in his pod, not with a parachute, which the Soviets feared could lead to their space flight failing to receive official recognition from the FAI, which demanded that a space explorer must complete the journey in his craft.

8. At first he resorts to his formidable social skills to answer the repetitive, sometimes inane, occasionally politically loaded questions he is asked during his unceasing trips abroad, gently evading answers about the space program or Soviet policy he is not entitled to give, even though he become the unofficial (smiling) face of Kremlin’s diplomacy. With time he develops routines, weaving corny space metaphors into his speech – a diamond shown to him reminds him of the Earth from space, while Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida is “brighter than any star he has seen up there.” Though frankly, he is so iconic, anything he says at all is a bonus, and crowds often just want to touch, embrace, or kiss him. When he gets back to his hotel room, he sews buttons onto his uniform to replace the ones torn away, though there is still time in the evening to be whisked away to the occasional jazz concert or cabaret.

9. Gagarin stays away from the sharper edges of politics in his pronouncements, and tries to humanize the clichés he delivers in his speeches with personal examples. But he is both a sincere Communist and unremittingly loyal, letting his name be used for all Soviet causes, for instance, the condemnation of internationally famous Soviet poet and internal dissident Evgeny Yevtushenko. He later tries to make it up to Yevtushenko in person.

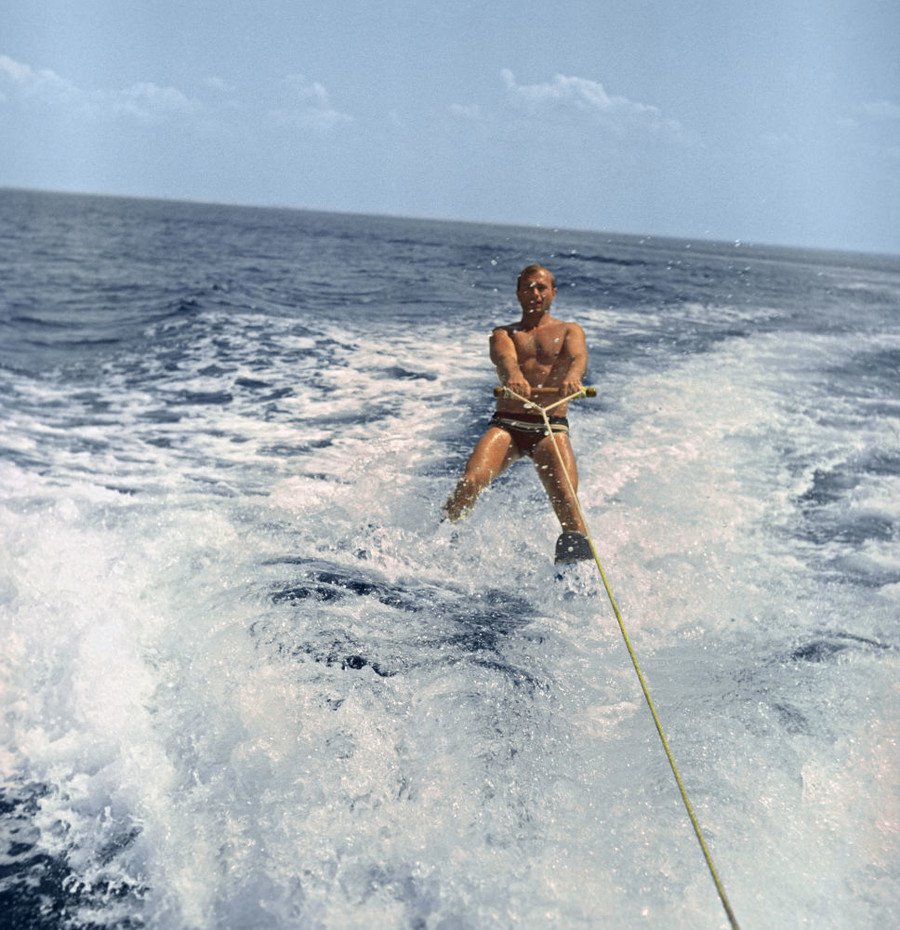

10. He begins to “dress like a dandy” and drives the only Matra Djet sports car in the whole of Moscow, making him an easy target for police officers, who haul him in for a chat. He “stops exercising systematically” and by the mid-1960s he gains about 8kg, with jowls below a receding hairline. General Nikolay Kamanin, his direct superior, notes with disappointment the “eagerness” with which Gagarin accepts offers for a drink, though just as often, he needs no invitation. Kamanin, a nationally-known war hero, whose aviation exploits far outstripped those of his charges, is the virtual chaperone for Gagarin, and his successor in space, Gherman Titov. After years in the barracks, where every decision was made for them, his proteges retain the dynamic of overgrown naughty schoolboys during a holiday in Crimea in 1961, sneaking away from their stern master to drive a speedboat, go fishing, or party at a local restaurant.

11. It is here in Foros, a patch of the Crimean coast beloved by the Soviet elite where his transgressions go beyond the tolerable. Anna Afanasova is one of the nurses at the sanatorium where he whiles away his hours playing billiards, and sneaking off for cigarettes. Unlike the others, she is not overawed by the spaceman, which inflames his desire only further (“No one chases those who want to be caught,” he supposedly tells her). On the final day, Gagarin gets so drunk he goes to bed in the afternoon, before getting up again in the evening to resume his carousing. On the verge of midnight he told his wife, Valentina, that he was going upstairs, but instead of his own room, somehow found his way to Afanasova. In her own words, Gagarin told her that he’d come to gift her a signed photograph, and then grabbed her arms and began kissing her. It is at this moment that Valentina’s voice rung out down the corridor, and outside the door. Realizing there was no easy explanation for this, the cosmonaut leaps straight out of the window, and falls down head-first onto the curb. Valentina runs out of the room, and screams that her husband is dead. He is not, but the seriousness of the injury exceeds the trivial circumstances. Severe concussion, fractured eye socket, and a scar that will unbalance his face for the rest of his life (“the Earth has left its mark,” he deadpans).

For the public a lie that he fell down carrying his young daughter; for the wife, a story about how he was going to give her a jump scare by rushing out of the room; and the truth – never to be known other than by those in that room. Whether the incident was typical of Gagarin, and whether any straying was a reflection of an early marriage collapsing under the strain of new temptations, is something that none of those involved have deigned to comment on.

12. Gagarin believes he will go to space again, and not just anywhere – but the Moon. He joked about going there with his comrades when he pilots his first plane a decade ago, before a space program even existed, and kids that he “came from the Moon” when people ask him where he’s been. He lobbies for funding, and Moon colonization is the subject of his doctoral dissertation. He reads books by great aviators, asks pilots on planes where he is a passenger to take control (they always let him), and demands ‒ and finally receives ‒ his license to fly again. On March 27, 1968 he boards his training plane for a standard test flight outside Moscow. Neither Gagarin, nor any other Soviets go to the Moon, and in December 1972 the USSR’s Moon program is shut down.

Igor Ogorodnev, RT