Scientists to make gravitational wave announcement 100 yrs after Einstein's theory of relativity

US scientists will make a presentation about the search for gravitational waves – and will possibly announce their discovery. Astronomers have been searching for decades, as they are one of the most important variables in Einstein's theory of relativity.

The presentation – which coincides with the 100th anniversary of the publication of Einstein's theory of relativity – will take place at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana, on Thursday. It will be conducted by Neil Cornish, a professor in the Department of Physics and co-director of the MSU eXtreme Gravity Institute.

“Cornish will provide a status report on the effort to detect gravitational waves – or ripples in the fabric of spacetime – using the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO),” the university wrote in a press release.

Advanced LIGO: Gravitational Wave Detectors Upgraded: https://t.co/IkksJGjhKC by LIGO, Caltech, @NSFpic.twitter.com/cXtcPJLAvt

— Astro Pic Of The Day (@apod) February 7, 2016

LIGO is a system of two detectors constructed to spot tiny vibrations from passing gravitational waves. It was developed and built by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Caltech researchers, and funded by the National Science Foundation and other contributors. The identical detectors are located 1,865 miles apart, in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington.

The system is set up on the assumption that if a gravitational wave passes, it should stretch space in one direction and shrink it in the other.

It looks out for those changes by splitting a laser beam in two and sending the beams from two distant locations. If the beams traveled the same distance when they return, they have not been distorted. However, if they do not align upon return, something has disrupted them during the journey – potentially gravitational waves.

Rumors have been circulating for weeks that the instruments have picked up a signal, and that researchers are working on a paper about the discovery.

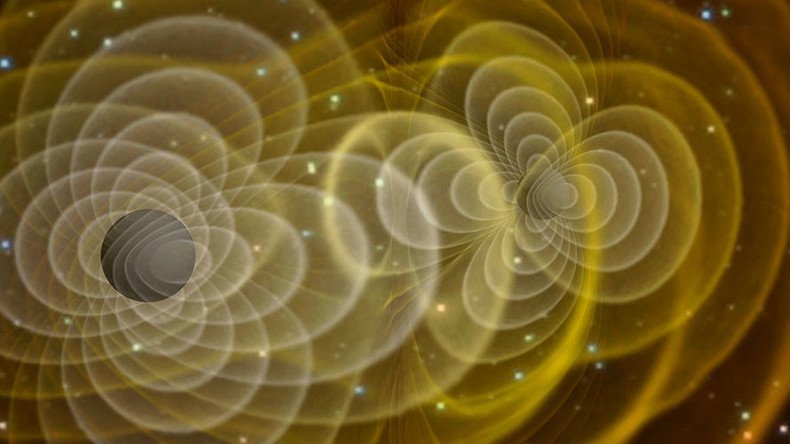

Einstein believed, as do those who support his theory of relativity, published in 1916, that the universe is made up of a “fabric of spacetime.” It is believed that massive accelerating objects in the universe bend this fabric, and cause ripples known as gravitational waves. For instance, they can presumably be caused by two black holes colliding, or two pulsars merging.

Astronomers have been searching for gravitational waves for decades, but have so far been unsuccessful. However, they are almost certain that they exist and are difficult to detect because by the time they reach Earth, the amount of spacetime movement they generate is incredibly small.

The discovery of gravitational waves would be a huge milestone for scientists, as it would allow them to observe the universe in a whole new way. The ability to analyze the information carried on them would potentially provide more insight into the Big Bang and other violent events in the history of the universe.

"They will carry information about their origins that is free of the distortion or alteration suffered by electromagnetic radiation as it travels through millions of light years of intergalactic space. With this completely new way of examining astrophysical objects and phenomena, gravitational waves will truly open a new window on the Universe, providing astronomers and other scientists with their first glimpses of previously unseen and unseeable wonders, and greatly adding to our understanding of the nature of space and time itself,” the LIGO website says.