Underwater electricity gave spark to life on Earth, NASA scientists say

There are lots of theories over how life on Earth came about, but there’s no doubt that energy is vital to living beings. NASA scientists proved that an underwater electrical boost may have been given to the first lifeforms.

We know one thing for sure: every living thing runs on electricity. It is required to produce the smallest of impulses and actions. Even thinking about something leads to synapses firing electrical currents back and forth. But where does that current come from and how did it come about that life needs it?

At this juncture, no one knows exactly what puzzle pieces led to the formation of life. But we’re getting closer. And scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, say they have just proven a monumental principle that was long theorized to be a major precursor to all life on Earth. And now we also know just how much electricity was needed to do so: under a volt.

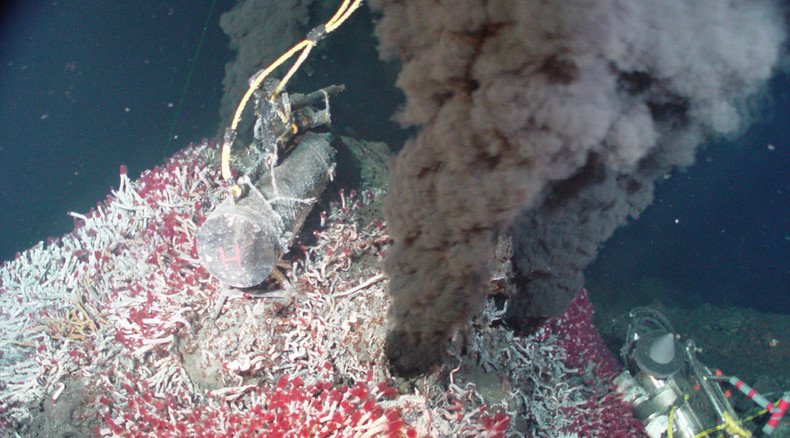

Many scientists have long believed the underwater hydrothermal vents are the answer; and that recreating those vents in lab conditions was the way to go to prove it. The chimney-shaped structures existing on the ocean floor and pumping out heat had already been recreated in lab conditions to test if the chemicals that bubble up from them spur the growth of molecules, bacteria, amino acids and so on.

Now it was time to take things up a notch and see if the vents could literally make electricity. And the results didn’t disappoint.

Called the ‘alkaline vent hypothesis’, the theory suggests that first life could not have made it without a hot boost of alkaline chimneys – tube-like structures that range from mere centimeters to several meters tall and are typically made from porous minerals.

Proposed in 1989 was the idea that the tiny membranes separating the compartments inside the vents contained within them electrical and proton gradients. Those gradients are thought to have emulated the processes critical to synthesizing living things. They did this by generating energy and organic compounds needed for simple organisms to grow.

"These chimneys can act like electrical wires on the seafloor," Laurie Barge with the JPL at Pasadena says. "We're harnessing energy as the first life on Earth might have."

Mankind’s missing microbe-link found in deep sea – study http://t.co/pGKIaF9EoIpic.twitter.com/Mqu4xTfuYt

— RT (@RT_com) May 7, 2015Great use can be extracted from the findings. The topic of the origins of life on our planet is full of pitfalls and wrongful assumptions.

"Life doesn't want to get electrocuted, but needs just the right amount of electricity," explains Michael Russell of JPL, the father of the hypothesis. "This new experiment confirms what that amount of electricity is – just under a volt."

Russell not only proposed the theory more than 25 years ago – he also theorized the vents’ existence a decade before they were discovered at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

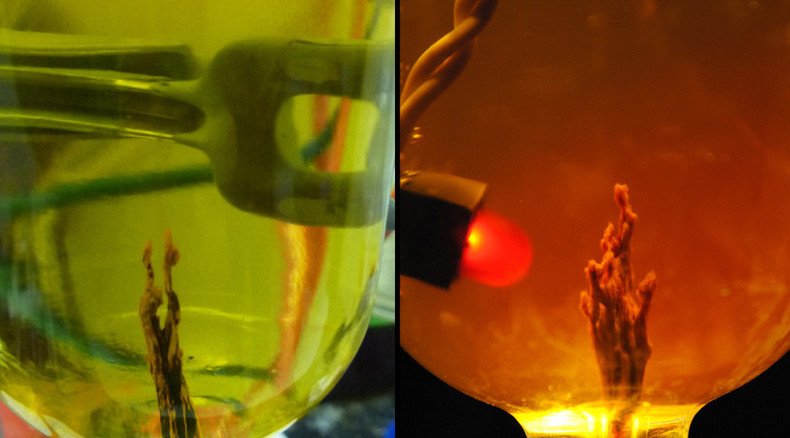

To prove the principle, the researchers submerged four chemical gardens in a fluid containing iron. That was all that was needed to get a light bulb to switch on, as Russell, Barge and Yeghegis ‘Lily’ Abedian, an undergraduate student and intern at JPL, proved.

"I remember when Lily told me the light bulb had turned on. It was shocking,” Barge recounts.

The chimneys were made of iron sulfide and iron hydroxide this time around – materials that can conduct electrons. But the team hopes to try new variations the next time around, when they assess the option that additional materials may have also contributed to the production of electricity.

"With the right recipe, maybe one chimney alone will be able to light the LED - or instead, we could use that electrochemical energy to power other reactions," Barge says. "We can also start simulating higher temperature and pressures that occur at hydrothermal vents."

Freeze-thaw cycles on Earth triggered life, new study claims http://t.co/eDYzbPQpvjpic.twitter.com/D3V7hyXeB9

— RT America (@RT_America) May 9, 2015This opens us up to exciting prospects – like testing materials thought to have led to marine life in the most intriguing places in our solar system, such as early Mars and present-day Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. The experiments would be a huge leap toward finding stuff out we previously could only ascertain while burrowing deep into Europa’s ice.

But electricity is just one piece of the puzzle, the JPL team explains. This and other accompanying studies – such as the one on how DNA seems to have spontaneously formed – will in time be assembled into a glorious singular vision of how life originates.