Secret of binging: Stress drives desire ‘for reward, not pleasure’

A new Pavlovian experiment on chocolate lovers from Switzerland has revealed that people under stress seek reward in self-indulging practices such as gambling, drugs, sex, or binge-eating – but don't necessarily gain extra pleasure from those activities.

For some, feeling stressed seems like a good excuse to eat a couple of sweets or pop open a bottle of alcohol. However, according to scientists at the University of Geneva, non-stressed people will typically derive pleasure more easily from those activities than stressed people will.

"Most of us have experienced stress that increases our craving for rewarding experiences, such as eating a tasty bar of chocolate, and it can make us invest considerable effort in obtaining the object of our desire, such as running to a convenience store in the middle of the night," said lead author Eva Pool in the press release. "But while stress increases our desire to indulge in rewards, it does not necessarily increase the enjoyment we experience."

In other words: Yes, you want that naughty treat oh-so-much. But no, it probably won't bring you any extra pleasure. So, will you consume more to try and quell your stress levels? Well, that’s a question.

Here comes chocolate

The research, published this week in the 'Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition' by the American Psychological Association, is based on an experiment on dozens of students who claimed they loved chocolate.

Three people were excluded for being under psychotropic treatment, as the scientists mentioned in their paper.

To stress out some of the participants, instructors asked them to put one hand in ice-cold water.

READ MORE: Fast food, slow kids: Eating junk leads to poorer academic results, study shows

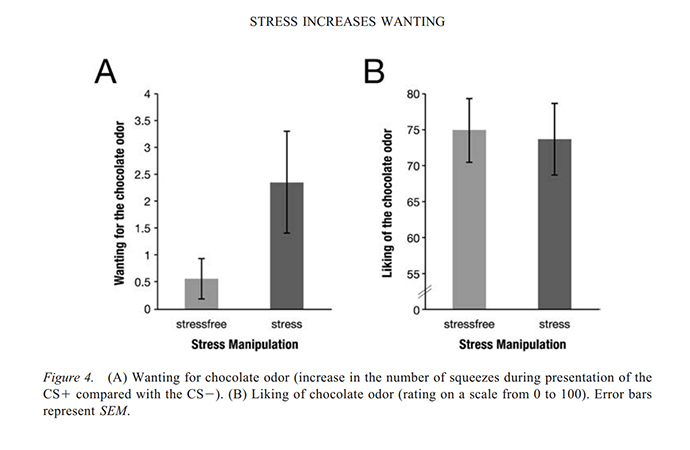

Following the test, the “stressed out” students had to exert three times as much effort to smell chocolate than the unstressed ones, who had kept their hands in lukewarm water.

However, the stressed group reported the same level of enjoyment from the delicious smell as the control group.

"Stress plays a critical role in many psychological disorders and is one of the most important factors determining relapses in addiction, gambling and binge eating," said another author, Tobias Brosch.

"Stress seems to flip a switch in our functioning: If a stressed person encounters an image or a sound associated with a pleasant object, this may drive them to invest an inordinate amount of effort to obtain it."

The research, which, in fact, needs further replications involving people, was based on a previous study with laboratory rats.

What made the experiment “comparable with relevant animal research” was the Pavlovian test, which excluded simple hedonistic drive. The researchers collected samples of participants' saliva to measure levels of cortisol, a hormone involved in stress response, before and after the test.

Participants also had to press a handgrip when they saw a special symbol indicating that they could have a chance to smell chocolate.

Wanting and liking can be separated and activated independently, as they rely on two distinct networks of neurons in the brain that only seem to correlate with each other, rather than being directly connected to one other, the research concludes.