Judge dread: What is the fate of the law in a key African state?

A confrontation has been unfolding in Kenya between the president and judiciary since last November, impacting significantly on the governance of the East African country.

After 1963, when Kenya gained its independence from Britain, the judiciary was perceived as an extension of the old government, and was perceived to protect colonial interests in its decisions.

It was therefore necessary to indigenize the institution by increasing the proportion of Kenyan nationals in key judicial positions. This process was slow and gradual, but it eventually resulted in a judiciary that reflected the true composition of the nation.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the government initiated a comprehensive strategy known as the Governance, Justice, Law and Order Sector (GJLOS) Reform Program. This recognized the importance of reforms in these areas for economic recovery. The enactment of a new constitution in 2010 positioned Kenya’s judiciary as an independent and effective guardian of the rule of law.

The constitution significantly restructured the judiciary, introducing measures to enhance its independence, accountability, and transparency. It also established the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) as an independent body responsible for promoting and facilitating the accountability and independence of the judiciary.

Elections results nullified

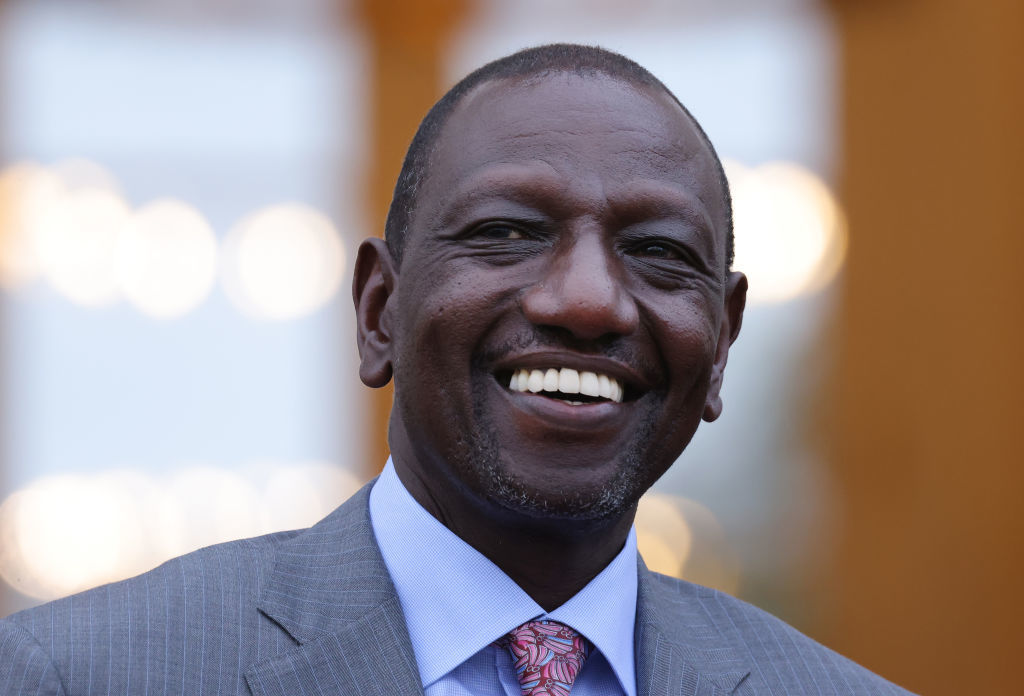

On September 1, 2017, Kenya’s Supreme Court made a historic ruling by nullifying the re-election of then-President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto, who is now the nation’s fifth head of state. In its ruling, the court said the country’s electoral commission had failed, neglected or refused to conduct the elections in accordance with the law, and the judges found that irregularities had compromised the integrity of the presidential poll.

It declared the election results invalid, null and void after finding that the elections had not been conducted in accordance with the requirements of the constitution, and ordered that a new poll be conducted in 60 days.

Opposition candidate Raila Odinga, who was the main petitioner in the case, refused to take part in the election re-run, demanding the reconstitution of the electoral body. Mr Kenyatta contested the re-run and won 98% of the vote.

This nullification of the presidential election results actually set a foundation for the beginning of a sour relationship between the government and the judiciary.

After their initial re-election for a second term was nullified, former president Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto described the Supreme Court judges as “conmen," and promised to deal with them.

In June 2021, Kenyatta declined to approve the appointment of six judges who had been nominated to serve in the Court of Appeal, and the Environment and Lands Court for “failing to meet the required threshold.”

The Kenyan constitution requires the president to approve the appointment of new judges after their nomination by the Judicial Service Commission. During his last term as president, Kenyatta and his government gained a reputation for disobeying and disregarding court orders, something President Ruto promised to rectify when he took office.

New president’s promises

When he took over in 2022, president Ruto announced that his first duty would be appointing the judges who had been rejected by his predecessor. During his campaign, Ruto has promised to appoint the judges and provide more funds to the judiciary. It had been expected by many that Ruto, who had fallen out with President Kenyatta, would reverse most of the decisions made by the previous administration, in which he had served as deputy president.

“My administration will respect judicial decisions while we cement the place of Kenya as a country anchored on democracy and the rule of law,” Ruto said during his swearing-in ceremony in the capital, Nairobi.

At the time, Ruto lauded the country’s Supreme Court for upholding his election, which had been challenged by the opposition, saying “the seven judges of the apex court demonstrated unmatched independence."

In the days that followed, President Ruto was frequently seen at events hosted by the judiciary.

Ruto fulfilled his promise and officially approved and swore in the judges who had been rejected by his predecessor. He also saw the operationalization of the Judiciary Fund to aid the planning and timely execution of judiciary operations and projects, and further eliminate previous challenges to delayed disbursements or budget cuts.

After slightly more than a year in office, however, Kenya’s head of state and the judiciary seem to be pulling in opposing directions after several courts delivered rulings that were not favorable to the government. When he took over, Ruto initiated massive reforms and projects that he counted on to fulfil his promise of providing jobs to millions of young people in Kenya.

Among the projects were an ambitious housing project that sought to construct affordable houses for millions of Kenyans. The majority of his flagship projects were halted by the courts after citizens filed petitions.

Confrontation begins

The confrontation between Ruto’s government and the judiciary started last November, when the High Court issued orders stopping the government from implementing a new housing levy to fund its affordable social housing scheme.

Judges stated the new tax lacked a comprehensive legal framework and was in violation of Articles 10, 201, 206 and 210 of Kenya’s constitution. The government then moved to the Court of Appeal to challenge the decision by the High Court but, on January 26, the appellate court upheld the decision, a move that did not go down well with the administration.

Following the ruling, President Ruto said his government would not tolerate what he described as “judicial impunity by corrupt judicial officers," accusing them of “deliberately trying to stall key government projects.”

“The impunity of bribing judges so as not to derail, delay, or sabotage Kenya’s imminent transformation will never happen under my watch. Not a single cent will be used to bribe anybody,” Ruto wrote on X (formerly Twitter).

He also accused unnamed judicial officials and people he described as beneficiaries of graft of teaming up to challenge his initiatives.

“A few people have gone to court and bribed the court to stop projects such as roads, universal health coverage and housing. We will not allow judicial tyranny and judicial impunity,” he said.

Mission to Haiti rejected

On January 23, 2024, another court declared the government’s plan to deploy police to Haiti as unconstitutional. President Ruto had committed to deploying 1,000 Kenyan police officers to lead a UN-backed multinational mission aimed at restoring peace and security in the troubled Caribbean nation.

In its ruling, the court said “any decision by any state organ or state officer to deploy police officers to Haiti contravenes the constitution and the law and is therefore unconstitutional, illegal and invalid.”

At some point, Ruto threatened to disobey court orders that restricted his key policies, and insisted that the plan to deploy police officers to Haiti remained on course.

“It is not possible that we respect the judiciary while a few individuals who are beneficiaries of corruption are using corrupt judicial officials to block our development projects,” he said.

The court also put a halt to the planned privatization of state agencies by Ruto’s government. In a national address in December, the president accused the judiciary of making decisions against state policies at the expense of the public interest.

However, Ruto did not publicly present any evidence of corruption nor did he name any individual judge when he accused them of illegal practices.

In January, during a church service, Kenya’s Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua announced that he would present a petition for the removal from office of Justice Esther Maina, a judge of the High Court, for alleged misconduct and corruption.

Gachagua claimed that Justice Maina had declared his wealth to be proceeds of crime without giving him a chance to defend himself. The deputy president would later back down after a meeting was called between the president and the chief justice.

Reuben Koborek, an MP for the ruling United Democratic Movement party, warned that parliament would be forced to slash the judiciary’s budget if the courts continued to issue unfavorable judgements against the government.

“Nobody including the president should use his position to sway judgements in their favor"

Ruto’s public attacks on the judiciary attracted condemnation, with Kenya’s Chief Justice Martha Koome calling on all judges and other judicial officers not to give into what she described as intimidation.

Koome told a press conference in Nairobi that the president’s attack on the judiciary had been a “recurring trend of discussing in public matters that are in courts,” something she said was intended to “intimidate judges to rule in a certain way.”

“It is regrettable that the leadership of the executive and legislature in their recent public declarations have threatened not to obey court orders,“ she said.

“These threats and declarations are extremely serious and a monumental assault on the constitution, the rule of law and the very stability of the nation, and can lead to chaos and anarchy in our motherland.”

The chief justice warned that disregard for court orders by the government would plunge the country into a constitutional crisis.

The Law Society of Kenya (LSK) also lashed out at Ruto, accusing him of intimidating the judiciary. Speaking to RT, outgoing LSK President Eric Theuri claimed that attacks by the executive on the judiciary were aimed at intimidating judges into giving rulings favorable to the government of the day.

“The intention is clear: to push judges into issuing rulings that the executive wants and this amounts to pure intimidation," Theuri told RT.

Brian Okoko, an advocate based in Kenya’s coastal city of Mombasa, warned that the intimidation of the judiciary could be “a recipe for the disregard of the rule of law.”

“We have a constitution that governs us and both the executive and the judiciary are bound by this constitution. Nobody including the president should use his position to sway judgements in their favor," Okoko told RT.

Lawyers protest

On January 12, lawyers held peaceful nationwide protests against the attacks on the judiciary, calling on the president to channel any complaints against judicial officers to the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) for investigations. The JSC is the body mandated to investigate and deal with cases of misconduct among judges.

Speaking to RT in Nairobi, Okiya Omtatah, a constitutional rights activist and senator warned that the attacks on the judiciary led by the president would likely erode public confidence in the most critical institution in any country.

“The judiciary exists to safeguard constitutional rights and the interests of everybody and to guarantee justice through civilized ways of conflict resolution but when a senior leader in the rank of a president attacks this institution, then the judiciary risks losing public trust," Omtataha told RT.

“The judiciary cannot be branded as bad and corrupt when it rules against our wishes."

Ruto’s meeting with the chief justice

After weeks of sustained attacks on the judiciary, on January 22, Ruto met the chief justice at State House in Nairobi, after which they both said in separate statements that “they were committed to upholding the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary.”

Opposition leader Raila Odinga described the meeting between the chief justice and the president as “an irresponsible move.” Odinga accused the executive of “trying to hold the judiciary hostage.”

International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) Kenya Chapter Chairperson Protas Saende told RT that the judiciary must maintain its independence, especially in the dispensation of justice and defending the rule of law.

“Any discussions that might seek to compromise the independence of the judiciary in administering justice and take over the disciplinary powers from the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) must be rejected in totality,” Sande said.

Days after the meeting between President Ruto and the chief justice, the Kenya Magistrates and Judges Association (KMJA) said it had “noted with deep concern the continued atavistic attacks against the judiciary, individual judges and magistrates by the political class even after the tripartite meeting.”

The KMJA warned that the courts would consider taking legal action against individuals attacking the judiciary and judicial officials.

What it means

The ICJ Kenya chapter warned that continued attacks on the judiciary would likely undermine the constitutional principles governing the separation of powers, and threatened Kenya’s rule of law and judicial independence.

Political analyst Bina Maseno observed that a war and falling out with the judiciary might greatly hamper Ruto's battle against graft, a key promise he made during his presidential campaigns.

“The judiciary is a critical component in the fight against graft because this is where those accused of graft should be charged. If the attacks on judges persist, then no judicial officer will be willing to preside over any graft case presented by the government, which will be a big blow to the president,” he told RT.

Maseno added that “any disregard of judicial decisions will likely affect Ruto’s international standing and there are development partners who will pull out in a situation where the government disregards judicial decisions.”

Lawyer Benard Ngetich warned that, if the government begins disobeying court orders and rulings, then the common man will have every excuse to act in the same manner.

“The rule of law states that if anyone including the government is dissatisfied by a court ruling, then they can proceed to a higher court for review and when the Supreme Court, which is the last resort, issues a verdict, then we all have to abide by it even if it may sound unpopular," Ngetich told RT.

He claimed that, if this trend is allowed to continue and the government gets away with it, then it may send a wrong signal to other African nations that a president or government can disregard court decisions.

“African democracies are fragile and if we cannot respect judicial institutions which are supposed to safeguard our democracy through the rule of law then we are on the path of destruction," he said.