The false choice of the Brexit referendum

As the Brexit referendum looms closer, British people probably feel that they have engaged in an exhausting level of public participation and that whatever the outcome of the referendum, democracy will have been served.

With the recent tragic murder of MP Jo Cox, questions have even been raised as to how easily vitriol may spill over into violence.

READ MORE: EU referendum: ‘Leave’ & ‘Remain’ make final pitch 24hrs before Brexit polls open

While, of course, a situation of mass political violence needs to be differentiated from the isolated criminal actions of Jo Cox’s deranged attacker, questions are rightly asked about how societies cope with issues that are as divisive as Brexit has proven to be, and how and why debate can become so irrational, if, mercifully, so rarely violent.

A key problem is that both elections and very occasional referenda are but crude tools for determining public opinion, and therefore, by their nature, they lead to oversimplifications of the issues at stake as well as a conflation of several issues into one umbrella question that different people may assume stands for different outcomes. Very general questions, such as whether or not Britain should leave the EU, become open to interpretation and therefore projection.

Aside from the extremely saddening attack on Jo Cox, little has been uglier in the Brexit debate than the issue of immigration, a point on which many Leave proponents believe that Britain has been too lax, and which they hope to restrict should a Brexit indeed occur. While this can hardly be deemed a selfless or altruistic view, reflecting all of the best mankind has to offer, it would be overly simplistic to categorize these views as purely motivated by racial hatred.

I personally suspect that if British people (whatever their ethnic heritage or genetic make-up) were skipping off to full employment after an affordable university education confident that, should they ever suffer a debilitating accident, a dignified and caring social safety net would be there for them, very few of them would really care whether their next-door-neighbors had blue-and-yellow stripes, flew a spaceship, and were building a temple to Baal in their backyard, much less what they happened to do for a living.

After all, everyone would have a backyard. And possibly even a house with an affordable mortgage.

I would argue that prosaically material things are at the bottom of what most people really want. But ‘Do you want a decent job?’ has somehow become encoded in, ‘Are there too many immigrants?’ – which has further been distorted to, ‘Do you think the EU sucks?’

It is the failure to address core issues such as the need for a living wage, a fair education system, and affordable housing that opens the door for this kind of proxy thinking on umbrella issues. Everything is interpreted into Britain’s membership or non-membership of the EU, but nothing is promised and nothing is certain.

And the fact that those core issues are not squarely addressed unto themselves by any side in the debate is no accident. The truth is that Brexit boils down to a choice between Neoliberalism by Hook or Neoliberalism by Crook, because at bottom the British national establishment and the European Union share similar methods of operation as well as similar policies.

While some may prefer to view a Leave vote as a resurgence of people’s sovereignty, the truth is that British ‘democracy’ has long operated more through skillful manipulation than genuine public consultation. In fact, the very form of voting in Britain is so inaccurate that electoral fortunes are often divorced from voter preferences for long years at a time.

In the 2015 election, for example, the Labour Party’s vote share increased by 1.4%, while the party lost 26 of its seats. It was a reversal of Margaret Thatcher’s results in the 1983 election – between 1979 and 1983, the Iron Lady lost nearly 700,000 votes, but gained dozens of seats in the House of Commons. As these examples indicate, the key to winning elections in Britain is not to win votes, but rather seats by channeling money into key ridings and ignoring lost causes. That money has inevitably come from wealthy interests, with both major parties having a history of courting everyone from real estate developers to financial investors, from media magnates to the alcohol industry. And since tickling money out of the wealthy requires some accommodation of their preferences, the British people now live under an aggressive program of disability cuts, healthcare privatization and labour casualization that only around a quarter of them ever saw fit to endorse with a vote.

There is no reason whatsoever to believe this essential state of affairs will change were Britain to leave the EU.

At the same time, while the will of the British people may have long been divorced from its politics, the European Union’s structure and policies are virtually identical.

The Remain campaign prefers to whitewash this by painting the EU as a group of bumbling bureaucrats. Former Deputy PM Nick Clegg, for example, recently lamented that it took the EU 30 years to agree to a “definition of chocolate – in part because the continental purists objected to the inclusion of vegetable fat, found in many British chocolate bars, as a key ingredient.” Clegg then claimed that, “[a] body that takes three decades to define chocolate can be described as many things — not least slow and bureaucratic — but an undemocratic conspiracy is hardly one of them.”

Unless, of course, you happen to know that the so-called Chocolate War that Clegg is referring to was not actually a dispute over confectionary tastes, but rather a concerted effort by some of the world’s largest chocolate manufacturers (Nestle, Cadbury, Mars, Hershey, Jacobs Suchard – owned by Philip Morris – and Ferrero), to open up the continental European market to their cheaply-produced chocolate.

Enlisting political institutions in trade wars is daily fare in Brussels. Browse through the European Commissioners’ online record of meetings and you’ll see that virtually every major global company, their lawyers, their PR agents and their sponsored groups of ‘independent’ experts meet with EU officials on a constant basis. From A for Apple to S for Sky to U for Uber, from G for Goldman Sachs to W for Weber Shandwick.

The results? While different businesses may be best served by slightly varying policies, non-business interests fall by the wayside entirely. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), and the crumbling of net neutrality are but a few of the recent policies to emerge from this style of ‘democracy.’

The Remain campaign is right about one thing and one thing only: this level of corporate involvement in policy-making should be so familiar to British people that they should feel right at home in Europe.

Just like there was no spoon in The Matrix, there is no actual choice in this referendum.

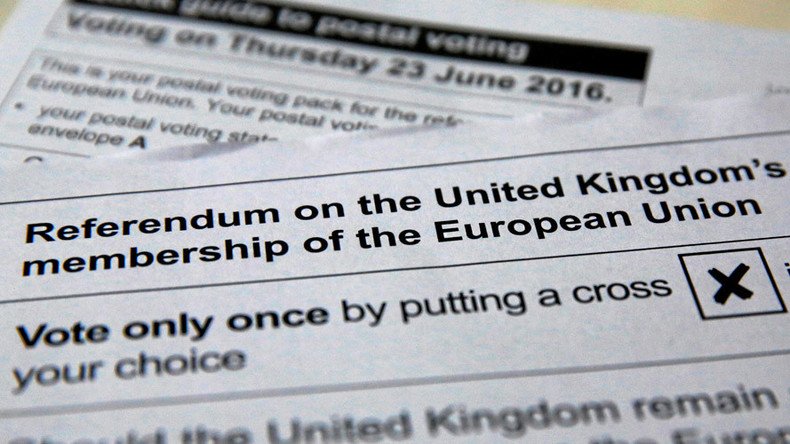

It may feel exhausting, and it may feel like everything under the sun from trade with China to national security has been discussed, but these issues have been discussed and speculated about only. None of them will appear on the ballot. The referendum itself will not directly address inequality, it will not address financial speculation, it will not address immigration policy or relations between the United Kingdom’s various regions. And despite the tragic murder of MP Jo Cox last week, nothing on the ballot paper will serve to make elected officials safer from violent attacks.

Instead the voter is asked to interpolate these issues into their vote, while guessing how a Brexit may affect them. This amounts to little more than scrabbling in the dirt trying to grasp the slightest advantage (real or imagined) between the promises and projections of wealthy and powerful Europhiles or wealthy and powerful Europhobes.

If the Brexit debate has been good for one thing, it has revealed the can of worms of simmering social issues in the UK. No matter what the outcome of the referendum is, it is highly unlikely that either the European or British elite will address these core points and, thus, tensions will continue to build. The debate will be over, but resolution will remain elusive.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.