Prosecutors in Aaron Swartz case targeted with threats

Documents pertaining to the federal investigation of Aaron Swartz will soon be made public, but first they’ll likely be redacted amid fears that those who aided in the prosecution of the late Internet activist will become the targets of harassment.

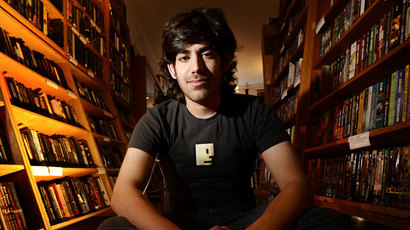

When Swartz, 26, committed suicide earlier this year, he left behind a legacy that has since been celebrated by a number of fellow activists and even members of Congress: Swartz co-founded the advocacy group Demand Progress, rallied for open access on the Web and helped code the website that eventually became Reddit.com. Upon his untimely passing, though, a highly controversial computer case that plagued the last two years of Swartz’s life was left behind as well.

The US Department of Justice eventually dropped their case against Swartz, but not until after his January 11 death. The DoJ had accused Swartz of illegally downloading millions of academic articles from the website JSTOR using a computer he left in a closet at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and if convicted he could have faced decades in federal prison. Attorney General Eric Holder would go on to say that government attorneys demonstrated “a good use of prosecutorial discretion” in going after Swartz, though friends and family of the activist have argued otherwise.

“Aaron did not commit suicide but was killed by the government,”Robert Swartz said while speaking at his son’s funeral earlier this year. “Someone who made the world a better place was pushed to his death by the government.”

In the wake of a widespread public backlash over what many have called prosecutorial overreach, MIT vowed to release documents that played a role in the federal investigation of Swartz. Only now, however, does the school say that it might have to hold onto some of that material. In a court filing last week, attorneys for MIT asked for those papers to be heavily redacted, citing concerns that those named in the investigation will come under attack: according to MIT’s legal team, Swartz’s suicide has triggered a number of cyberattacks waged at the school, and the people that pursued the case against him have become the targets of serious threats as well.

MIT says that the material should be censored because information identifying persons that played parts in Swartz’s case — investigators and others — could be the next victims in a wave of threats that have already targeted the school’s administrators and the Justice Department officials that accused Swartz of violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

“Since Aaron Swartz’s death on January 11, 2013, the MIT community has been the subject of threats to personal safety and breaches to its computer network, apparently based on MIT’s involvement in the events relating to Mr. Swartz’s prosecution,” begins a memorandum filed on Friday in support of the school’s motion to intervene and partially oppose a motion would bring those documents into the spotlight. “Despite these threats and breaches, MIT values openness, and in fact intends to release a report of its involvement in the Swartz case, along with related documents,” it continues. “Such openness, however, must take into account and address the potential for significant harm to individuals and MIT’s network.”

Less than two weeks after Swartz’s death, MIT’s computers were successfully compromised by no fewer than three cyberattacks: one in which a school website was defaced in tribute to Swartz and two instances where the university’s email system was hit by hackers. Releasing information about those attacks, attorneys fear, could expose vulnerabilities that would once again open the school up for exploitation.

Outside of the network, though, MIT’s attorneys worry that threatening messages and other future harassment may single out persons who played a role, substantial or not, in Swartz’s prosecution. The latest court filing reveals that supporters of Swartz have already taken a number of actions to voice their grievances against the Justice Department lawyers assigned to prosecute the activist, some that have even been perceived as death threats.

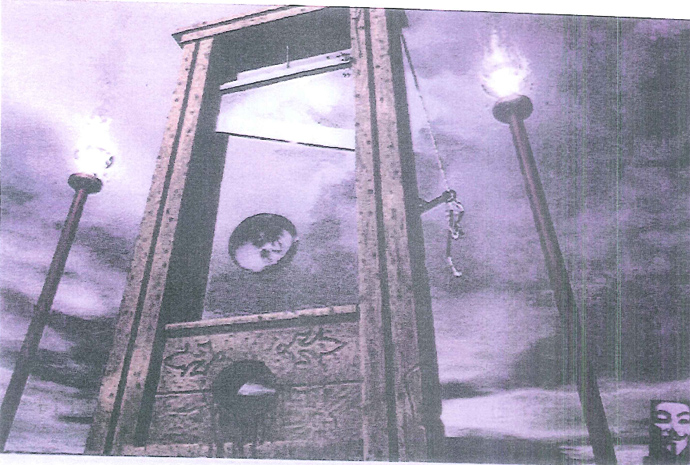

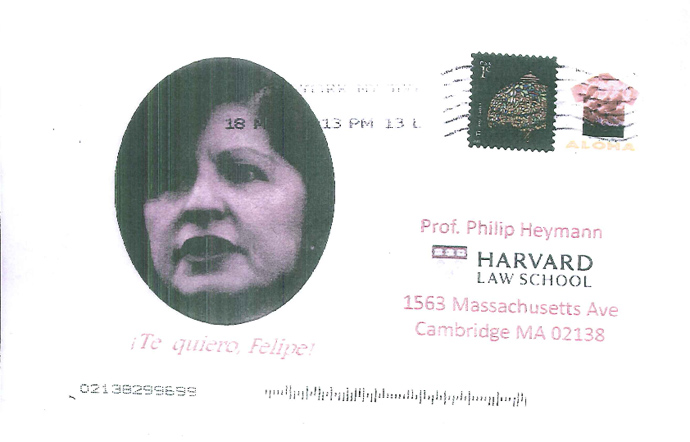

Cited in the motion are postcards that were sent to Stephen Heymann — a prosecutor in the Swartz case — and his father, Harvard Law professor Philip Heymann. The prosecutor, writes Pirozzolo, received a postcard that contained a crudely doctored image of US Attorney Carmen Ortiz’s disembodied head with the caption “Heckuva job, Steve” on one side, and a photo of the MIT president’s head under a guillotine on the other. The older Heymann allegedly received mail in which his own likeness was represented under the blade of the execution machine.

Ortiz has been singled out separately a number of times as well, including last month when three masked men protested outside of her suburban Boston home with a cake that was decorated to read “Justice for Aaron.”

Also cited in the motion are comments posted by readers of a Huffington Post article about the case. “I hope the MIT officials live with that fear for the rest of their lives for what they did,” one critic wrote. “If the courts will not punish these killers, the people must,” said another.

Submitted in evidence along with the comments is also a collection of emails sent to MIT’s administrators through the school’s website.

“Please pass on my contempt for the MIT Fascists who drove Aaron Swartz to his death. They will for ever [sic] be tarnished with this legal hounding of a genius,” reads just one of the messages. “Shame on them.”

"We know two simple things," Jack W. Pirozzolo, first assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Massachusetts, writes in the court filing. "First, there is now an unrestrained desire of unidentified individuals and groups to retaliate against people and organizations associated with the prosecution of Mr. Swartz and their family members. Second, the more people’s names and their involvement in the events leading up to the arrest of Mr. Swartz is publicized, the more likely they are to come to the attention of these vindictive individuals and groups and the more likely they are to be subject to harassment and threats."