Neck & neck Brazil presidential race casts doubts on Mercosur, BRICS

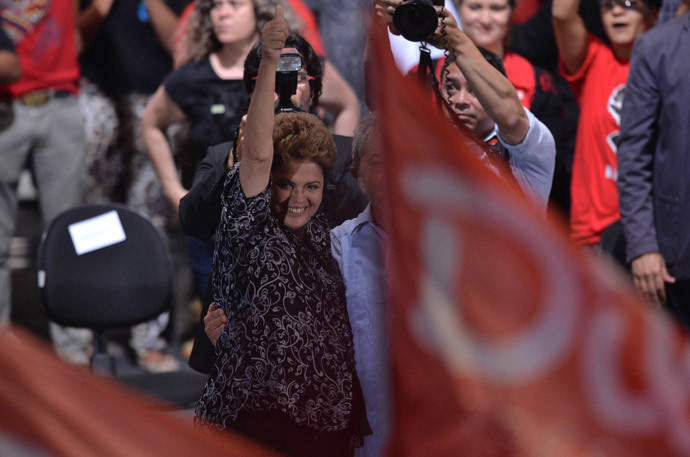

About a year ago everyone expected an easy ride for President Dilma Rousseff in her reelection campaign. Now, in the final week of Brazil’s election season, she is technically tied with opposition’s Aécio Neves.

About 20 percent of voters, who reject both candidates or seem too tired of politics to show up on October 26, are hearing desperate claims from the incumbent and her antagonist. It is likely Brazilians only know what will happen after the last vote is counted. That uncertainty makes the country’s future a big mystery. And that includes a big chunk of South America’s powerhouse foreign policy.

Neither Rousseff nor Neves want to give away much of what they intend to do if victorious. But the president’s closest allies have given hints. Rousseff’s foreign advisor Marco Aurélio Garcia says “South America is a big asset” and insists Mercosur - the region’s free trade zone - must be strong to keep Brazil’s position as a Latin American spokesman. Neves’ aide Rubens Barbosa, a former ambassador to Washington, says Brazil does better by imploding Mercosur (which includes Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay), so there is a deal with the European Union and diplomacy that is friendlier to the US.

Rousseff has shown the intention of improving her relationship with the Americans, which deteriorated after Edward Snowden informed that her phone was being hacked by the NSA. But that doesn’t mean she would scrap off the bank of BRICS nations, just launched with the presence in Fortaleza of Russian, Chinese, Indian and South African leaders. Neves’ appointee for the Finance Ministry, former Central Bank Governor Arminio Fraga, thinks differently about any state banks.

“I don’t know if there will be much left of them,” he said, in a reference to Brazil’s state banks fostering credit - which led to rising debts.

Brazil’s tradition is of a close relation with the US, which was interrupted by president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2003. He decided fight for a seat in the United Nations Security Council by becoming a regional leader and starting trade agreements with peripheral countries, including Africa and the Middle East. The big attention to China was also a milestone of his diplomacy.

Neves bets on a return to the traditional. Some of his excitable fans say that getting further from the US put Brazil closer to Cuba and Venezuela. If the opposition wins, Neves will have to hear those distorted views in order to govern.

Another important doubt lies with who Brazil’s foreign minister will be if Neves wins. The two frontrunners for the job are environmentalist Marina Silva, who lost her place in the run-off in the final week, and former São Paulo governor José Serra - a man who thinks Bolivia and Peru should get penalties for not stopping drugs from entering Brazil. Serra is also a critic of policies of BRICS leaders, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping.

If Rousseff is reelected, she is likely to keep minister Luiz Alberto Figueiredo, but there is pressure from Lula for her to bring back former minister Celso Amorim. Amorim crafted the diplomacy that is less dependent on the US and Europe. Those doubts most likely won’t end after the results are announced. The future of Brazil’s foreign policy could be known just by December, since whoever wins has a mandate beginning on January 1st of 2015.

But it’s all too close to call.

History says a bit about this moment in the campaign trail. Neves got a bump after beating Silva for the place in the run-off. But the final week of the campaign, in which emotional arguments tend to weigh more, could tip the balance towards Rousseff and her predecessor Lula - his presence on the TV screens has a strong impact in Brazil. The dead heat is making both candidates more aggressive, taking swipes at each other like Brazilians haven’t seen since 1989, in the first direct elections for the presidency since 1961.

Neves is betting on holding Rousseff accountable for a scandal at Petrobras, the country’s oil-giant. Brazilian federal police discovered a scheme under which officials were taking kickbacks from contractors to pay to political parties - mainly the President’s Worker’s Party. Some of that cash allegedly paid for her campaign in 2010. Although Brazilians tend to see her as an honest person, her party has accumulated too many corruption accusations since 2003, which has put many of her supporters off in this election.

The president is aiming at Neves himself and scandals involving nepotism and the construction of a small airport on land belonging to one of his uncles - the keys to the place were with his family during the time he governed Brazil’s second most powerful state, Minas Gerais. Media is more sided with Neves than with Rousseff, but the debates on national TV have been essential to level it all up. Brazilians watch more television and read little.

In the final days there will be also be campaigning in battleground states São Paulo and Minas Gerais. Neves is likely to win in both, but the margins are going to be decisive since Brazil’s northeast states will go massively with the government candidate anyway. In those, foreign policies won’t make any difference - what counts is the triumphant social programs and the sluggish economy in the past four years.

Although the election is still Rousseff’s to lose, the gap is becoming narrower and narrower. The expectation now lies on undecided voters making a choice soon before going to the polls. According to the Datafolha Institute, 13 percent of undecided voters could still vote for the president. Neves could get the support of 6 percent of the doubtful voters. That is why both candidates have become so aggressive in the last two weeks: by stimulating rejection of the other, they can get some voters out and fire up their fans to go to the polls. So far, Rousseff’s rejection is at 42 percent and Neves’ is at 38 percent - a draw in the limit of the margin of error.

Brazil’s place in the world in the next four years depend on how they appear to the public this week and on undecided voters believing their lives have improved enough in the last four years.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.