Big Bang? No, Big Chill! Australian scientists challenge universe creation theory

A team of Australian physicists have come up with their own theory on the universe’s creation. Challenging the “Big Bang” model, they now say it was a “Big Chill” – somewhat similar to water first freezing into ice and then cracking upon cooling.

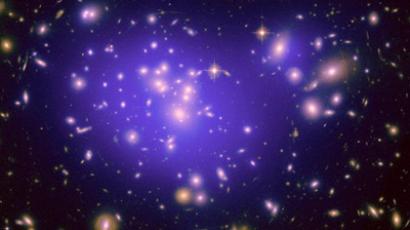

Researchers from the University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) brushed away the theory of the start of the universe as being a “big bang”. That model posits that our universe apparently inflated, expanded and cooled, going from very, very small and very, very hot and dense, to the size and temperature of our current universe. The followers of this prevailing theory believe it continues to expand and cool to this day.The Australian physicists, however, put forward a new concept which suggests that the secret to understanding the origin and nature of the early universe is in the cracks and crevices common to all crystals, including ice. The idea is that the early universe was liquid-like and it cooled, crystallized, and possibly cracked. Their report was published in the journal Physical Review D.Their research rests on a school of thought that has emerged recently. A new theory, known as Quantum Graphity, suggests that space may be made up of indivisible building blocks, like tiny atoms. These indivisible blocks can be thought of as similar to the pixels that make up an image on a screen. The challenge however has been that these building blocks of space are very small, and thus impossible to see.The Australian scientists now believe they may have figured out a way to see these “building blocks” – indirectly."Think of the early universe as being like a liquid,” says James Quach, a lead researcher on the project, who did the study as part of his PhD. "As the universe cools, in a similar way that water freezes into ice, structure becomes emergent. You get the 3D space we see around us, but also like water freezing into ice, you get defects.""The reason we use the water analogy is water is without form,” Quach explained. "In the beginning there wasn't even space. Space did not exist because there was no form."Just as ice cubes in our fridge crack, so did space, the theory goes.Quach and colleagues calculated the way light is scattered by these cracks and say that it is now possible for experimental physicists to look for this effect."Light and other particles would bend or reflect off such defects, and therefore in theory we should be able to detect these effects," says RMIT University research team member Associate Professor Andrew Greentree. Quach says this theory would be more complete than the Big Bang theory, which is based on Einstein’s theory of general relativity, but is unable to explain the moment of the Big Bang itself."Ancient Greek philosophers wondered what matter was made of: was it made of a continuous substance or was it made of individual atoms? With very powerful microscopes, we now know that matter is made of atoms," said Quach."Thousands of years later, Albert Einstein assumed that space and time were continuous and flowed smoothly, but we now believe that this assumption may not be valid at very small scales," he added.The team now says if their predictions are experimentally verified, the question as to whether space is smooth or constructed out of tiny indivisible parts will be solved once and for all.