Facts you need to know about Crimea and why it is in turmoil

With its multinational society and a long history of conquests, the Crimean Peninsula has always been a crossroads of cultures – and a hotbed of conflicts. Amid Ukrainian turmoil, every ethnic group of Crimeans has its own vision of the region’s future.

What is Crimea?

Now known as Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the picturesque peninsula shooting out into Black Sea from mainland Ukraine was for centuries colonized and conquered by historic empires and nomadic tribes. Greeks, Scythians, Byzantians and the Genoese have all left traces of their presence in Crimean archeological sites and placenames.

The Russian Empire annexed the territory of Crimea in the last quarter of the 18th century, after a number of bloody wars with the Ottoman Empire.

As part of the 1774 Kuchuk-Kainarji peace treaty the Crimean Khanate, previously subordinate to Ottomans and notorious for its brutal and perpetual slave raids into East Slavic lands, aligned itself with Russia. Soon Empress Catherine the Great abolished the Crimean Khanate, giving them a historic Greek name of Taurida.

Soviet citizens got to know Crimea as an “all-Union health resort,” with many of those born in the Soviet Union sharing nostalgic memories of children’s holiday camps and seaside.

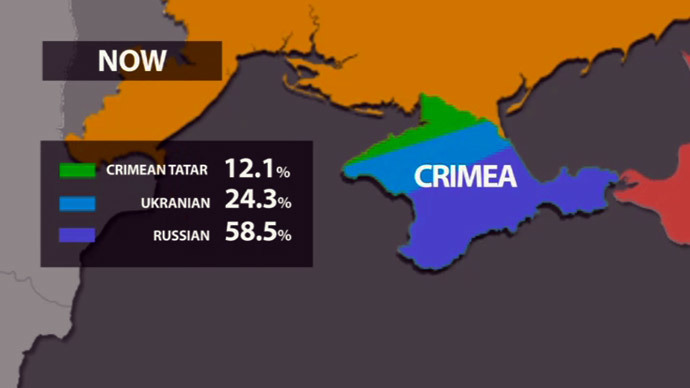

Who lives there now?

The majority of those living in Crimea today are ethnic Russians – almost 1,200,000 or around 58.3 percent of the population, according to the last national census conducted back in 2001. Some 24 percent are Ukrainians (around 500,000) and 12 percent are Crimean Tatars. However, in the Crimea’s largest city of Sevastopol, which is considered a separate region of Crimea, there are very few Crimean Tatars and around 22 percent of Ukrainians, with over 70 percent of the population being Russians.

An absolute majority of the Crimean population (97 percent) use Russian as their main language, according to a Kiev International Institute of Sociology poll. One of the first decisions of the interim Kiev government directly hit Crimea, as it revoked a law that allowed Russian and other minority languages to be recognized as official in multicultural regions.

What's happening now?

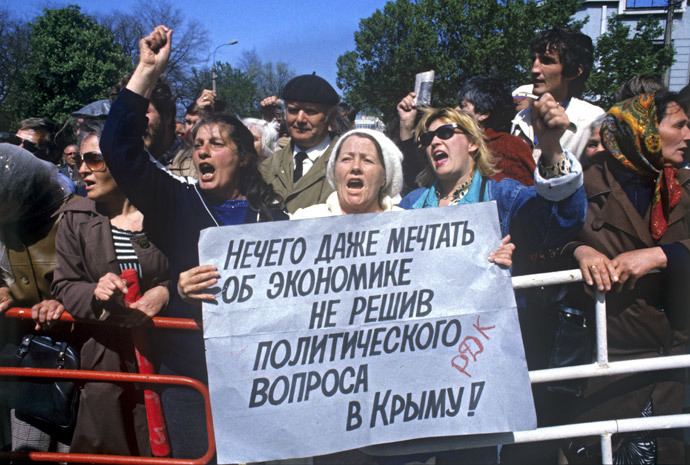

After the Ukrainian President was ousted and an interim government was established in Kiev, the Russian majority started protesting outside the regional parliament, urging local MPs not to support it. They want the Autonomous Region to return to the constitution of 1992, under which Crimea briefly had its own president and independent foreign policy.

The parliament of the Crimean Autonomous Region was due to declare on Wednesday the region’s official position toward the new authorities in Kiev. The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars has spoken out sharply against holding a parliamentary session on the issue, expressing their support for the new central authorities. Back in 2012 members of the Mejlis ran for parliamentary elections as part of Yulia Tymoshenko’s bloc and remain active supporters of the revolutionary Kiev government.

Two separate rallies, consisting of several thousand protesters, faced each other in front of the parliament building in the Crimean capital, Simferopol. Two people have died as a result of scuffles and stampede and about 30 were injured, before the head of the Mejlis, Refat Chubarov, called for the participants of the rally to go home peacefully. While the Mejlis represents only around 20 percent of the minority, they claim to be the voice of the whole Tatar population. Many of the Crimean Tatars actually participated in the stand-off on the side of pro-Russian forces.

Following the example of Kiev, vigilante groups are being formed, with about 3,500 people already patrolling the streets of Crimea along with police to prevent any provocations.

After the central government in Kiev disbanded the Berkut special police task force, new authorities in Sevastopol have refused to comply and welcomed all Berkut officers who feel intimidated to come to live in Crimea with their families. Sevastopol earlier elected a new mayor after the popular gathering ousted the local government, which tried to cling to power by pledging allegiance to Kiev’s new rulers.

Impact of 2014 change of power in Kiev

Turmoil in the Crimean Autonomous Region began after the new Ukrainian authorities revoked a law that gave legal grounds for regional use of minority languages, including Russian. The 2012 law allowed predominantly Russian-speaking regions of Ukraine to use Russian in official business, education and some other areas.

The new government in Kiev has also proposed an initiative that would prohibit members of the former regime from occupying official posts.

Abolition of the regional language law sparked controversy throughout Ukraine. Even in the most nationalistic western regions of the country, people spoke against the reforms.

In the stronghold of the far-right opposition, Lvov citizens announced a day of the Russian language, calling on all locals to speak Russian for one day in solidarity with the Russian population of Ukraine.

How was Crimea separated from Russia?

In 1954, a controversial decision of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, himself an ethnic Ukrainian, transferred the Crimea peninsula to the Ukrainian SSR, extracting it from Russian territory.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev’s “gift” has been widely criticized by many Russians, including the majority of those living in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Adding to the confusion was also the status of Soviet-era Sevastopol, which not only remained the largest Crimean city, but also retained its special strategic and military profile. In 1948, Sevastopol was separated from the surrounding region and made directly subordinate to Moscow. Serving as an important Soviet naval base, it remained a “closed city” for years.

In the 1990s, the status of Sevastopol became the subject of endless debates between Russia and Ukraine. Following negotiations, the city with the surrounding territories was granted a special “state significance” status within the Ukrainian state, and some of the naval facilities were leased to Russia for its Black Sea Fleet until at least 2047. However, the city’s Russian majority and some outspoken Russian politicians still consider it to be a part of Russia.

Ethnic controversy

By the beginning of the 20th century, Russians and the Crimean Tatars were equally predominant ethnic groups in Crimea, followed by Ukrainian, Jewish and other minorities. Crimea was both a royal resort and an inspiration for some of the great Russian poets, writers and artists, some of whom lived or were born there.

During WWII some 20,000 Crimean Tatars allied with the Nazi German occupants, but many others also fought the Germans within the Soviet Army. Citing the collaboration of Crimean Tatars with the Nazis, Joseph Stalin ordered the whole ethnic group to be deported from Crimea to several Central Asian Soviet republics. Officially, 183,155 people were deported from Crimea, followed by about 9,000 Crimean Tatar WWII veterans. That made up about 19 percent of the Crimean population on the eve of war, almost half of which was by then Russian.

While the move was officially criticized by the communist leadership as early as in 1967, the Tatars were de facto unable to return to Crimea until the late 1980s. The tragic events surrounding Stalin’s deportation obviously shaped the ethnic group’s detestation of the Soviet regime.

Referendums and hopes

In 1991, the people of Crimea took part in several referendums. One proclaimed the region an Autonomous Republic within the Soviet Union, with 93.26 percent of the voters supporting the move. As the events unfolded fast, another one was already asking if the Crimeans supported the independence of Ukraine from the Soviet Union – a question that gathered 54 percent support. However, a referendum on Crimea’s independence from Ukraine was indefinitely banned from being held, leading critics to assert that their lawful rights were oppressed by Kiev authorities.

Complicating the issue was the return of the Crimean Tatars, who not only started to resettle in tens of thousands, but also rivaled local authorities. The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People was formed to represent the rights and interests of the ethnic minority. Although it was never officially recognized as an official organization, the body has enjoyed undisputed authority over most of Crimean Tatars and has successfully pushed for some concessions for the ethnic group in local laws.

While the Crimean Tatar re-settlers and the peninsula’s current Russian majority have learned to understand one another as neighbors, hardcore politicians from both ethnic groups also created grounds for a heated standoff. Calls for wider autonomy and aggressive lobbying for Crimean Tatar rights have prompted several pro-Russian Crimean political leaders to call the Mejlis an “organized criminal group” leading “unconstitutional” activities. The remarks sparked furious claims of “discrimination” from the Crimean Tatar community.

What happens next?

The ultimate goal of the ethnic Russian population protesting in Crimea is to hold a referendum on whether the region should retain its current status as an autonomous region in Ukraine, to become independent, or become part of Russia again. In the meantime, they claim to have a right to disobey orders of the “illegal” central government.

The Mejlis Tatar group, meanwhile, feels that ethnic Russians are trying to “tear Crimea away from Ukraine” excluding them from deciding the land’s fate. They however represent only a small portion of the Tatar minority, while the rest remain apolitical or even support the Crimea’s right for self-determination.

Right-wing radicals from Western Ukraine earlier threatened to send the so-called “trains of friendship” full of armed fighters in order to crush any signs of resistance to the revolution they were fighting so hard for.

The Kiev authorities busy with appointing roles in the revolutionary government in the meantime embraced a soft approach towards Crimea. The interim interior minister even did not undertake any “drastic measures” to arrest fugitive ousted President Yanukovich, fearing that may spark unrest.

Russia repeatedly confirmed it does not doubt Crimea is a part of Ukraine, even though it understands the emotions of the residents of the region. This week Russian MPs initiated a bill that will allow Russian citizenship within six month if the applicant successfully proves his or her Russian ethnicity. It is prepared especially to save Russian-speaking Ukrainians from possible infringement of their rights.