Good Friday Agreement: Has Brexit put Northern Ireland’s peace at risk?

Northern Ireland has big problems. It has been without a government for a year and now Brexit threatens to exacerbate border issues. On the 20th anniversary of the region’s seismic peace deal, there are still challenges ahead.

The issue of a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is a major sticking point in Brexit negotiations. The current frontier is essentially an open one, allowing people to travel freely around the island of Ireland.

But 20 years after the Good Friday Agreement brought a fragile end to decades of sectarian violence, the region is facing a potential ‘hard Brexit’ which could see the Irish border revert to a physical barrier, dividing the UK from the EU and re-emphasizing the partition between Northern Ireland and the Republic. To fully comprehend the potential impact of Brexit, we must first understand the Good Friday Agreement.

The peace deal

The Good Friday Agreement was reached between Northern Ireland’s main political players on April 10, 1998, signalling a long-awaited shift away from the horrors of three decades of violence known as ‘the Troubles’.

More than 3,500 people were killed and 50,000 injured during the conflict, which saw sectarian violence between the unionist and loyalist Protestant population and the nationalist and republican Catholic minority. This included shootings, bombings, rioting and burning houses.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and other republican groups waged an armed campaign against the British state, including the Royal Ulster Constabulary or RUC (police), the British Army and the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), a local unit. They viewed the struggle as a guerilla war against the British, while the UK and Irish governments considered the violence as terrorism.

Paramilitary groups on the loyalist side included the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). They said their attacks were carried out to stop the republican violence against protestant civilians, but in reality, Catholic civilians were the main target.

In 1994, a ceasefire was called by the IRA and the loyalists followed suit. After years of talks, the governments of the UK and Ireland, along with political parties in Northern Ireland reached a consensus on how the region would be governed.

Northern Ireland was to be ruled with a power-sharing government of unionists and nationalists. Paramilitary groups agreed to decommission their weapons and paramilitary prisoners were released. The UK normalized its security presence in the region, while the right of people in Northern Ireland to hold Irish, British or dual citizenship was officially recognized.

While the agreement was ratified by popular vote in May 1998, in Northern Ireland, only 52 percent of Protestants voted ‘yes,’ compared to 96 percent of Catholics, signalling sectarian challenges would continue.

There will be no #Brexit: Irish border mess shows why clean UK break is impossible (Op-Edge) https://t.co/Me4Uq3B1UB

— RT UK (@RTUKnews) March 3, 2018

The Republic of Ireland removed its territorial claim to the entire island from its constitution and the UK gave up direct rule of Northern Ireland. Cross-border cooperation between the Irish and Northern Irish government was set in motion as was a closer working relationship between the UK and Ireland.

But has this cooperation been emperiled by a return to tensions?

Brexit divisions

Northern Ireland’s biggest political parties, Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), campaigned on opposing sides of Brexit, with the DUP strongly supporting the UK’s departure from the European Union. Northern Ireland voted against Brexit, with 56 percent voting to remain in the EU.

The DUP and Sinn Féin entered a power-sharing government in 2006, but in 2017, the administration broke down. Sinn Féin walked away from the power-sharing assembly over the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal – a government-sponsored clean energy initiative for businesses which ran way over budget – and the DUP’s refusal to recognize the Irish Language Act. Northern Ireland has now been without a government for over a year.

Sinn Fein vow to battle 'the Tory-DUP wrecking-agenda' after EU release N. Ireland planhttps://t.co/bmSk0n2k99

— RT UK (@RTUKnews) February 28, 2018

UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s impromptu election last June has further fuelled tensions after she entered an arrangement with the DUP in an effort to retain power in Westminster. The deal prompted concern that the Good Friday Agreement was being violated, as both the UK and Ireland are supposed to act as neutral brokers.

The development has added significant weight to concerns over Brexit, as the issue of a hard border dividing the island of Ireland could mark a return to sectarian tensions and undermine the peace agreement. Demilitarizing the border area was a key element of the peace process, and reinstating military checkpoints would be an unwelcome sight for many on both sides of the divide.

May’s DUP deal also raised fears that the UK’s departure from the EU, against the wishes of the majority of voters in Northern Ireland, could see a return to violence of the past.

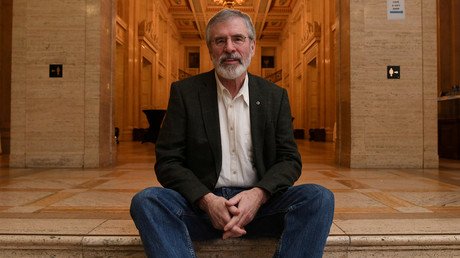

“The British government conducted a referendum on Brexit, totally ignoring, perhaps oblivious to, the damage it would do to Ireland,” former Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams recently told Der Spiegel. “The North voted against Brexit. If the English Tories have their way, there will be a hard economic border. That's going to be totally and absolutely disastrous.”

‘Armed actions’ legitimate in certain circumstances – Gerry Adams https://t.co/kgPNmDsLv0pic.twitter.com/Mik3Y3H9OD

— RT (@RT_com) April 8, 2018

As of now, when one drives across the border it can be very difficult to tell that you have crossed what is officially a national boundary. No checkpoints, barriers, soldiers or passports. One simply keeps driving. But any practical reinforcement or reminder that a divided Ireland still exists – which would come about with the return of a hard border – will likely irk anyone of a nationalist persuasion.

Earlier this month the leader of Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland, Michelle O’Neill, demanded a referendum on Irish unity within five years, claiming “Brexit exposed the undemocratic nature of partition.”

Any border poll is bound to heighten tensions in Northern Ireland and it appears Brexit has brought such a prospect a step closer.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!