Queen Nefertiti’s tomb still intact next to Tutankhamun’s, claims leading archeologist

New high-definition images of the tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun show a sealed secret passageway to what is likely the resting place of one of Ancient Egypt’s most famous figures, Queen Nefertiti, says a well-known British researcher.

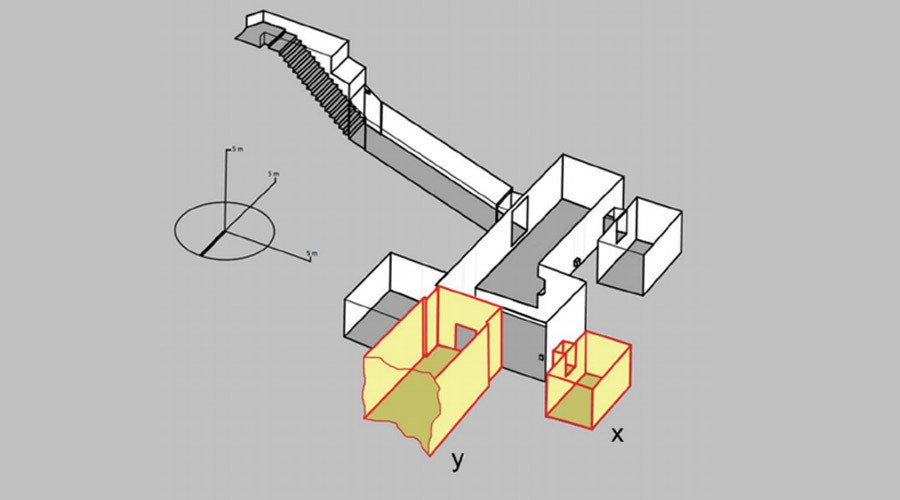

Known as KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun, who died in 1323 BC while in his late teens, was discovered 93 years ago, almost untouched. Since that time, examination of the burial site has been exhaustive. Just last year, a Spanish team charged with building a facsimile of the tomb published detailed photographs and three-dimensional scans of the walls online, which have been pored over by Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves.

“Cautious evaluation of the scans over the course of several months has yielded results which are beyond intriguing: indications of two previously unknown doorways, one set within a larger partition wall and both seemingly untouched since antiquity,” writes the University of Arizona professor in a paper published as part of the Amarna Royal Tombs Project.

“If digital appearance translates into physical reality, it seems we are now faced not merely with the prospect of a new, Tutankhamun-era storeroom to the west; to the north appears to be signaled a continuation of tomb KV62, and within these uncharted depths an earlier royal interment – that of Nefertiti herself, celebrated consort, co-regent, and eventual successor of pharaoh Akhenaten.”

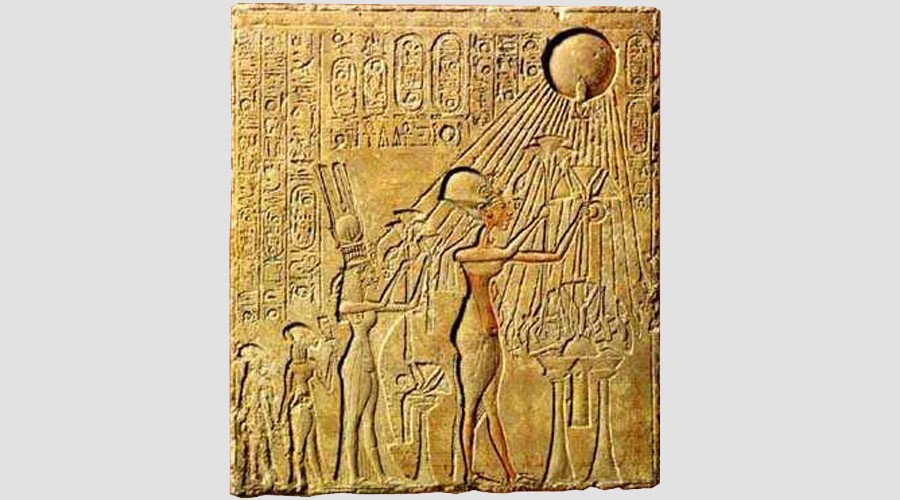

Akhenaten and Nefertiti are the most famous power couple of ancient Egypt, arguably responsible for introducing the first monotheistic religion in history, when they spurned worship of the pantheon of Egyptian deities, in favor of Aten, the sun-disk.

In contemporary depictions, Nefertiti is shown alongside Akhenaten wearing symbols of power, and Reeves believes she reigned over the most advanced civilization in the world for at least several months while sickly Tutankhamun, likely a product of incest, was still a child.

She died before 1330 BC, aged around 40, some years before Tutankhamun. Her death was likely the result of plague, though plausibly came at the hands of courtiers unwilling to accept her rule.

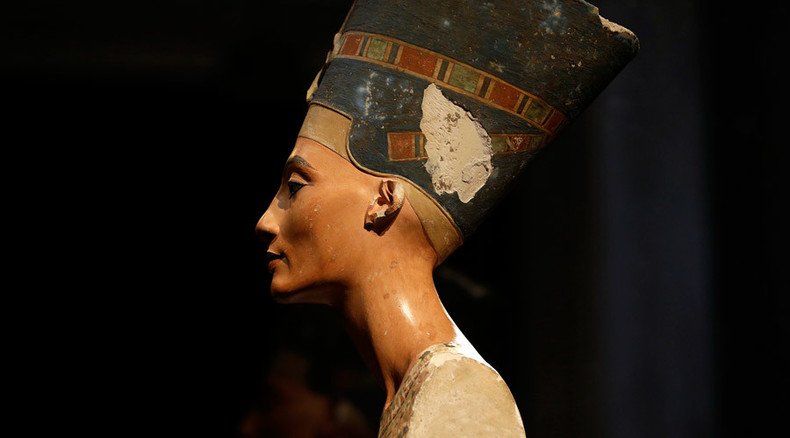

Unlike the majority of Egyptian royals from the Eighteenth Dynasty, Nefertiti’s sarcophagus has not been found in the Valley of the Kings, where pharaohs and powerful nobles were buried from the 16th to 11th centuries BC. However, a famous bust of her perfect facial features – her name means The Beautiful One Has Come – has stretched her allure beyond interest in her political and religious life.

Reeves deduces that the tomb was usurped by Tutankhamun, after his “unexpected” demise “obliged ancient undertakers to improvise.” He reached this conclusion using circumstantial evidence, such as the presence of Nefertiti’s iconography on the walls, and the “burial equipment” – shrines, sarcophagus and masks – that appears to have been passed down from her deceased husband, and not intended for his son.

“At the time of Nefertiti’s burial within KV62 there had surely been no intention that Tutankhamun would in due course occupy this same tomb. That thought would not occur until the king’s early and unexpected death a decade later. With no tomb yet dug for pharaoh’s sole use, KV62 was reopened and accessed. This restricted space was then physically enlarged to receive a second burial,” writes Reeves.

For casual observers it may seem implausible that, for nearly a century after its discovery, no one found the newly revealed chambers within the walls of one of the most celebrated dig sites on the planet. However, academics have been broadly receptive towards the theory.

“It’s certainly tantalizing what Nicholas Reeves has suggested,” Toby Wilkinson, an Egyptologist at Cambridge University, told CNN.

“If we look at what we know: we’re pretty certain there is an undiscovered royal tomb of roughly the same period somewhere, because we have more kings than we have tombs, so logic suggests that there’s still a tomb to be found.”

“The pharaohs were masters of deception. They didn’t need laser lights and razor wire, they could design a tomb which would appear to finish naturally, but then continue,” he said. “To discover a royal burial, now, and, in the Valley of the Kings would be phenomenal,” Nigel Hetherington, an Egypt-based British archeologist told the Telegraph.

Reeves himself, who has previously led several expeditions to Egypt, has called for a new excavation.

“It goes without saying that a final determination on the presence or otherwise of additional elements within KV62, and their precise character, will be made only on the ground. Obviously a full and detailed geophysical survey of this famous tomb and its surrounding area is now called for, and I would suggest as one of Egyptology’s highest priorities,” he writes in the paper, which has been read more than 40,000 times since publication.

But while the finds may bring joy to archeologists, they will also be a reminder of the tragic fate of both royals.

Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s worship of Aten was quickly dismissed as heresy, and many reminders of their reign were physically scrubbed and wiped from history during Tutankhamun’s rule. Meanwhile the young pharaoh, whose mother was his father’s sister, likely died suffering from malaria and club foot after fathering two stillborn children with his own half-sister. With no offspring, one of Egypt’s most famous dynasties collapsed within several years.