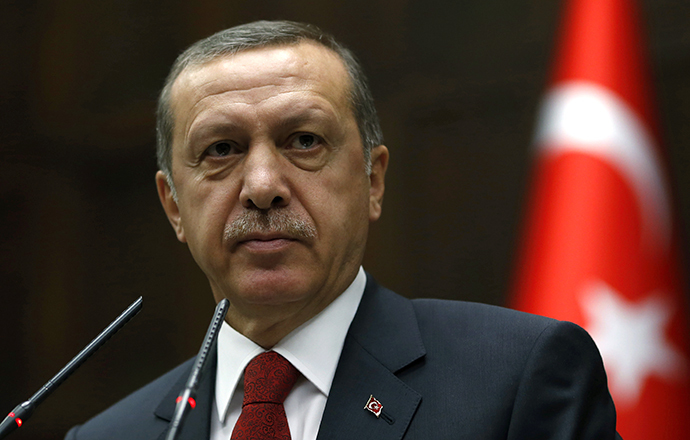

'Shared pain': Turkish PM Erdogan in historic Armenian statement

In a statement to mark the 99th anniversary of the Armenian genocide carried out by the Turks in 1915, Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan stressed the “shared pain” endured during those events and expressed “condolences” to Armenians around the world.

In a statement issued by the prime minister’s office, and which is being seen by some people on social media as an apology, Erdogan said April 24 is of “particular significance for our Armenian citizens and for all Armenians around the world.”

Erdogan was referring to the tragedy on April 24 1915, when hundreds of thousands of Ottoman Armenians were deported by the Turks in what has been described as one of the 20th century’s worst genocides. Men were massacred or died through forced labor, while women and children died on death marches into the Syrian desert; in total, up to 1.5 million people are believed to have died.

In a statement that stopped short of being a full apology, Erdogan said that during the later years of the Ottoman Empire all its people lived under difficult times. Erdogan described the events as “inhumane” and used more conciliatory language than previously.

“The incidents of the First World War are our shared pain. To evaluate this painful period of history through a perspective of just memory is a humane and scholarly responsibility,” he said.

The statement, which was released in nine languages, including Western and Eastern Armenian, also stressed the importance of free speech and plurality when discussing history. Turkey also argues that many Muslims also died in an ethnic conflict in a disintegrating empire.

“Expressing different opinions and thoughts freely on the events of 1915 is the requirement of a pluralistic perspective as well as of a culture of democracy and modernity,” the statement said. “It is with this hope and belief that we wish the Armenians who lost their lives in the context of the early 20th century rest in peace, and we convey our condolences to their grandchildren.”

Armenians demand that Ankara recognize what happened and make a full apology, whereas Turkey claims the events should be interpreted in the context of the First World War.

Most historians however, regard the events as a deliberate attempt to exterminate the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire. Earlier this month, a US Senate committee resolution branded the massacre as genocide.

Turkey recognized Armenia as a nation when it the Soviet Union broke up in 1991, but closed its land border with Yerevan in 1993 and has not established diplomatic ties its small landlocked neighbor because of Armenia’s invasion of the Nagorno-Karabakh region and part of Azerbaijan during a war in the early 1990s.

Armenia and Turkey signed a protocol in 2009, which aimed to normalize relations between the two countries and which had an indirect but clear reference to the study of the genocide issue. The negotiations between the two states stalled in 2010 and the land border remains closed.

Last December, Turkey’s foreign minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, made the first high-level trip to Armenia of a Turkish official in nearly five years, raising hopes that peace efforts could be revived.

Erdogan has in the past stopped short of denouncing the policies of the Ottoman Empire and their killing of hundreds of thousands of Armenians. Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) follow a political philosophy derived principally from religious concepts rather than secular nationalism; this gave him the chance to denounce past policies as part of an extreme nationalist and statist ideology. But this is not what he did.

While now Erdogan’s government is making some effort to hold an olive branch out to the Armenians, it may not be enough to heal an old wound between these two historic rivals.