‘They stopped seeing us as human beings’: How Europe provoked a savage modern genocide in the heart of Africa

“Our neighbors moved away from us, and we found ourselves isolated. They called us snakes. They stopped seeing us as human beings. Only a handful of neighbors came to drink at the bar I ran, the biggest bar in the area,” Dafrosa, a survivor of the 1994 genocide, recalls. “Markets and shops appeared where we were forbidden to shop. There they refused to sell us food; the cashiers said, ‘take your money somewhere else.’ From 1990 to 1994, politics began to divide people more and more. Segregation became commonplace. At first, there was no hostility in our church, but in other churches, the parishioners were divided and even refused to give communion to the Tutsis.”

The horrific events of April 1994 put an end to the illusion that the end of the Cold War and the ‘democratization’ of Africa would lead to years of peace and prosperity.

RT recalls how the bloody genocide began in Rwanda and whether it was possible to avoid.

How it started

On April 6, 1994, two surface-to-air missiles shot down a plane as it approached Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Then-President of Rwanda Juvenal Habyarimana and President of Burundi Cyprien Ntaryamira, on their way from peace talks in Arusha, Tanzania, died in the plane crash, along with seven other passengers.

The military, headed by retired Chief of Staff Theoneste Bagosora convened an interim government and declared that the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) headed by Paul Kagame had been responsible for the attack. By that time, the RPF had been engaged in an armed conflict with the government for many years, and advanced towards the capital from the side of Uganda.

On that tragic night, Bagosora at a meeting of the General Staff of the Army tried to negotiate a transfer of power to the military but faced opposition from Romeo Dallaire who led the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) at that time.

First of all, the conspirators got rid of moderate politicians. Among the victims were Prime Minister Agathe Uvilinhiyimana, Chairman of the Constitutional Court Joseph Kavaruganda, as well as a number of ministers and leaders of opposition parties. Their assassination greatly undermined any resistance efforts. Bagosora’s call for ‘revenge’ was supported by commanders, local authorities, and political experts, and was broadcast on Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) and other media.

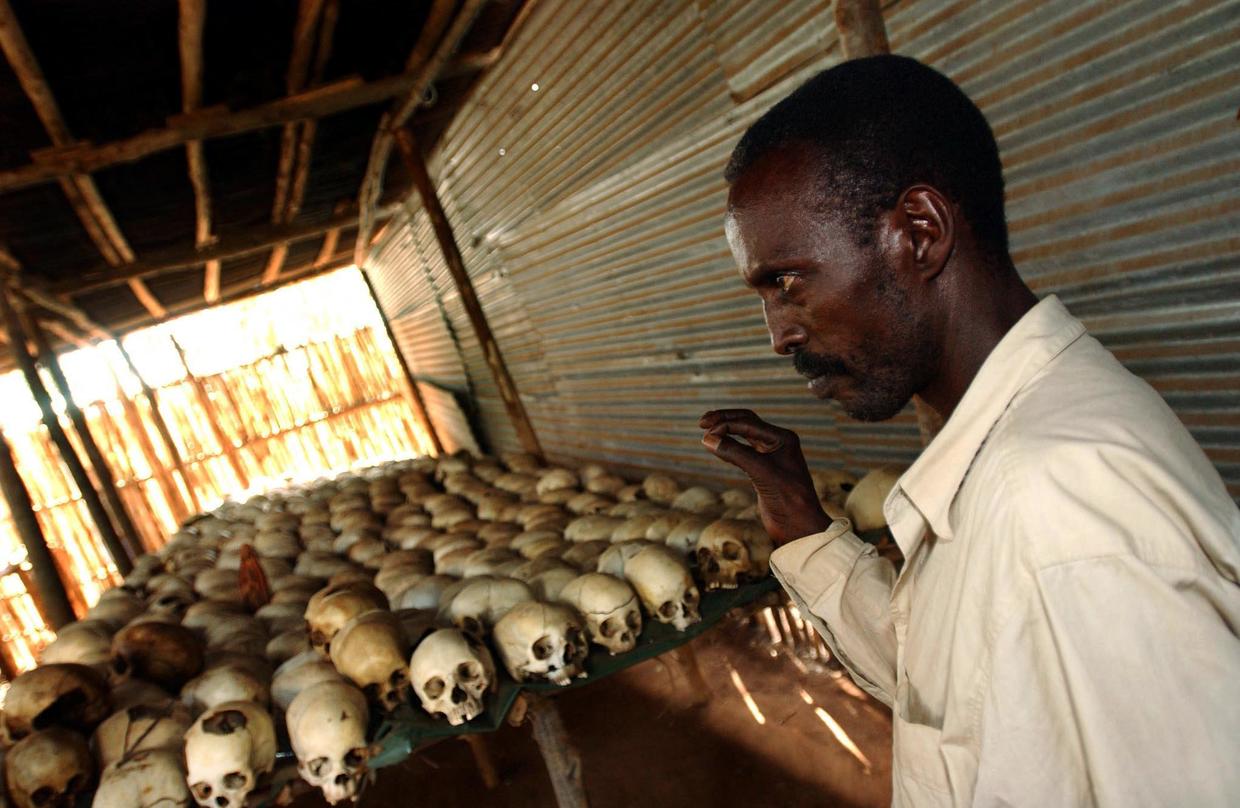

100 days of genocide

Mass killings began in Rwanda’s Gisenyi Province (considered a stronghold of the authorities) just a few hours after the plane crash. By the next day, they spread to six more provinces, including the capital. The Presidential Guard, gendarmerie, Interahamwe youth detachments (‘interahamwe’ translates from Kinyarwanda as ‘those who work/fight together’), and ordinary people grabbed machete blades and agricultural tools, and wiped out the ‘Tutsis’, identified through documents or pointed out by their neighbors.

The wave of deadly violence began to decline as the RPF seized new territories in the north and east of Rwanda. In May and June 1994, the genocide continued on the territory which was not controlled by the RPF, while most of the intended victims had already been killed, the officials tried to direct the violence into the fight against Kagame’s detachments.

The mass murder of unarmed people went on throughout the country for about three months, leading to the death of several hundred thousand people. Though estimates vary depending on the time frame and other criteria, according to the Government of Rwanda, the official death toll is 1,074,107. The international community and the UN contingent stationed in Rwanda could not agree on any effective measures and merely watched the tragedy unfold.

During the about 100-day genocide, the RPF’s struggle with Habyarimana’s regime continued, and so did the conflict within the ruling regime – between supporters of the “moderate” course and the “radicals” led by Bagosora, who rejected any negotiations with the RPF. The genocide was eventually stopped, RPF troops led by Kagame entered the capital. From then and for many years, the RPF established itself as the undisputed ruling party in Rwanda, and the key partner for any external player in the region.

In the aftermath of the tragic events of 1994, Rwanda was devastated, its GDP plunged dramatically, and the political landscape in the African Great Lakes region changed completely.

According to a Russian researcher Ivan Krivushin, the genocide was not initially planned as a full-scale elimination of all Tutsis, but as a “political cleansing” of the actual or potential opponents of the regime. However, this got out of control promptly and dramatically.

The role of France

It is a widely reported that France maintained close relations with the Rwandan officials, responsible for the genocide, right up to its culmination. Many Rwandans even believe that, in the summer of 1994, a limited contingent of French troops was sent to the country in order to help France’s close allies among the government officials to escape (Opération Turquoise).

Having come to power, Paul Kagame reduced the influence of France in his country to a minimum. On the official level, Rwanda abandoned the use of the French language and switched to English. It also joined the Commonwealth of Nations headed by Britain. In its first years, Kagame’s government received major support from the US, but later, driven by both historical and economic reasons, Rwanda formed a multi-vector partnership system that was increasingly oriented towards the East – for example, China and the UAE.

Where the ‘Tutsis’ and ‘Hutus’ came from

It is often claimed that the ‘Tutsis’ and ‘Hutus’ are ethnic groups. This is not at all the case, since the differences between these imposed and outdated categories are rather social. The Tutsis and Hutus, — at the time these categories were in use, — spoke the same language and inhabited the same territory. They were historically part of one society and closely interacted with each other.

In modern-day Rwanda, division into ‘Tutsis’ and ‘Hutus’ is wisely abandoned and forbidden – all residents are Rwandans, and the descendants of the former Hutus and Tutsis get along very well. But this does not mean that these categories could not be reinstated in the future, should someone want to start another conflict.

Binary oppositions were always an important factor in the development of European culture. But in traditional African societies, hybrid identity was much more widespread – a person is often identified with several social and cultural groups, and the social structure allowed people to ‘switch’ their social identity multiple times in the course of life.

The ‘Tutsis’ and ‘Hutus’ became known as a result of complex overlapping processes, including migration, assimilation, and the division of labor in society. The ‘Tutsis’ owned cattle, and generally had bigger incomes and more weapons. The ‘Hutus’ people worked the land. In pre-colonial Rwandan society, the ‘Tutsis’ represented the traditional hereditary aristocracy. Both groups spoke the same language, their traditions and customs were part of a single culture. The cultural boundaries were often blurred, and this served as an antidote to conflicts.

For example, a member of the ‘Tutsi’ community could become a ‘Hutu’, and vice versa. Some people weren’t part of either group, or considered themselves members of both groups. In European terms, they were one nation, but represented different social groups.

However, German and later Belgian colonialists needed a way to effectively manage and control the population of Ruanda-Urundi (the colonial territory that preceded modern Rwanda and Burundi), particularly since the Europeans were few in number. Searching for a model of colonial governance, they resorted to racial theoriespopular in Europe at the time (and not just in Germany). Based on these groundless theories, the taller ‘Tutsis’, who allegedly came from the north, were innately superior to the thickset ‘Hutus’.

The genocide was not an accident nor a sudden, unforeseen event. It was a deliberate terror campaign directed against the assumed supporters of the RPF. By April 1994, this campaign had reached its apogee and resulted in deliberately organized mass killings of unarmed people.

Rwanda today: no division

Over the past 30 years, Rwanda has been focused on building a united nation and avoiding any division into ‘Hutus’ and ‘Tutsis’. Progress in this respect is evident – the country has risen from the ashes, ensured sustainable economic growth, and turned into a regional stronghold of stability and security.

However, the opposition between the ‘Hutus’ and ‘Tutsis’ persists around. In Burundi, the percentage of Hutus and Tutsis in leadership positions is fixed at legislative level. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), various groups resort to ethnic rhetoric (e.g. the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda), and the risk of instability is greater than ever before.

Genocide and population growth: the greatest manipulation

In 1992, a report titled ‘Beyond the Limits’ was released, which warned about the threat of overpopulation on our planet. The report was published by the Club of Rome – one of the most influential behind-the-scenes non-profit organizations, notorious for its struggle with overpopulation. From an informational and ideological point of view, the report has strongly influenced how conflicts in Africa (including those in Rwanda) are viewed by the world.

The massive, months-long massacre, in the course of which ordinary people killed their unarmed neighbors practically with their bare hands, seemed to illustrate the horror into which the planet could plunge as a result of overpopulation and a lack of land, resources, and food. Several authoritative articles and monographs published in Europe and the US convinced the world that the tragedy in Rwanda had happened precisely because of overpopulation.

From this, an obvious conclusion was drawn that birth rates in the Global South – from Latin America to China – must be limited in order to avoid the repetition of the Rwanda scenario in countries like Nigeria or China. In reality, the Club of Rome and certain Western elites came to this conclusion in the interests of preserving their global supremacy and preventing the transfer of power to the world majority in the East and South. After all, the rise of the West to power and colonial expansion would have been impossible without the ‘demographic explosion’ that had once happened in Europe.

The myth about the overpopulation of Earth, including the ‘population trap’ and the food-shortage trap that humanity can fall into, is among the biggest information manipulations of the late 20th century. It has been based on a considerable number of ‘expert’ reports and scientific papers, publications, and discussions. However, by the second decade of the 21st century, it became clear that reality was a lot more complicated, and demographic growth in countries such as China, India, Ethiopia, and Nigeria actually ensured the development of infrastructure, agriculture, and allowed these countries to eliminate hunger. Today, all this is obvious, but in 1994, the genocide in Rwanda seemingly proved the opposite: that global overpopulation leads to catastrophes.

Thirty years have passed since the Rwanda genocide. Following a significant population decrease – from seven million people in the late 1980s to five million by the end of 1994 – by now, the population of Rwanda has surged to 14 million. Rwanda remains the most populous country in continental Africa, and is also one of the leaders in terms of economic growth. In terms of population density in Africa, Rwanda is surpassed only by Mauritius – which could well be the most prosperous country on the African continent.

Economic growth today

The supposed connection between population density, falling living standards, and food crises in Africa was merely an unsuccessful hypothesis. The expected growth of Africa’s population to three billion people in the coming decades is likely to solve the problem of hunger through market growth, infrastructure development, and agricultural production.

In Rwanda itself, economic growth is evident. In the past 30 years, crop production has increased more than sixfold, both due to increased agricultural productivity and because of new land included in agricultural turnover.

The length of paved roads has doubled to 1,200 km, exports increased from $100 million to $3 billion, and the capacity of power plants has increased sevenfold to 230 MWh. The growth of the Rwandan economy isn’t just a result of the balanced development of infrastructure, but is also due to the consistent development of the tertiary sector of the economy. In 2022, Rwanda’s tourism revenues amounted to $445 million. An important contribution in this regard is made by RwandAir, which offers 24 direct routes to 21 countries.

Why did it happen?

As for the causes of the genocide, we can now affirm that it was caused by external and situational factors. The electoral ‘democracy’imposed by France did not take into account the country’s traditions of governance and the class structure of Rwandan society.

The criminals who came to power united their supporters under the guise of protecting the interests of the ‘Hutus’, and incited people to violence, which was driven by induced class hatred. Meanwhile, external forces, including arms suppliers and smugglers, made money from the conflict. It was also convenient for the West as a means to justify its agenda and maintain its leadership position. Nevertheless, France was badly affected by the Rwanda genocide. In fact, the demise of Francafrique and the crisis in relations between Paris and Africa that has reached its apogee today, dates back to 1994.

What’s next: regional hubs, polarless policy, external impact

It is common practice for countries (and not just in Africa) to move their capital cities inland, away from coastal areas. In Africa, the most successful example of this is Abuja in Nigeria, and Dodoma in Tanzania may be next. This step signifies a change in the country’s system of development, as it moves away from a semi-colonial structure – when the country’s life depends on trade with the outside world through one or two large ports – to self-sufficiency ensured by internal growth resources and intraregional cooperation.

The next step is the formation of regional integration hubs in the inland parts of Africa, which would serve the needs of the entire continent. Such hubs are very important for the continent’s future. Rwanda is already turning into a remote communications and logistics center for Africa, and a distribution hub for the entire African Great Lakes region.

The construction of a new airport in southern Rwanda in partnership with Qatar Airways, and the construction of the Kigali dry port with DP World – a Dubai-based infrastructure and logistics company – can turn Kigali into an important transport hub and business center. However, the volume of foreign-exchange earnings is still insufficient to ensure the country’s continuous and rapid growth, and this remains a problem.

However, the part of the economy related to the processing and re-export of minerals from the DRC, as well as the supply of necessary goods (e.g. energy, food, medicines, and equipment) to the Eastern Congo market may ensure long-term growth, considering the growing global demand for Congolese metals. In order for this to happen, Rwanda needs to preserve a porous border with the DRC and expand its economic and political influence in North and South Kivu provinces. Peace – or at least keeping the conflicts in this part of Africa under control – is also an important prerequisite.

Among other things, Rwanda remains a positive example of a multi-vector and polarless policy characteristic of Africa. Qatar and the UAE are now forced to compete for Kigali’s attention. Even France, despite the painful history of relations between the two countries, remains among Kigali’s partners. Rwanda also maintains smooth, friendly political relations with the US, China, and Russia.

If it were not for external pressure on the DRC and Western attempts to limit China’s influence in Africa, the neighboring countries would certainly come to an agreement. Objectively, the DRC is interested in economic growth and development in its eastern regions, which would be impossible without Rwanda’s involvement. However, in recent years the conflict between Kinshasa and Kigali has escalated, acquiring sinister features which bring to mind the situation 30 years ago.

Statements by Western governments, which take an increasingly pro-Congolese stance, make the authorities in Rwanda nervous and contribute to the escalation. Nevertheless, for both Kinshasa and Kigali, it is more profitable to keep Goma (a city in the eastern region of the Congo) as a trading hub and logistics center, rather than turn it into a site of bloody battles. The tragic story of the Rwandan genocide demonstrates that the less external forces meddle in the region’s affairs, the greater its chance of living in peace and focus on development.

In July 2024, Rwanda will hold presidential elections. If the current president, Paul Kagame, is to be re-elected for another five-year term, he will have to once again prove the effectiveness of the country’s post-1994 management model.